A new working paper examines the relationship between competition policy and the decline in the labor share across the developed world and finds that effective competition policy may be an important factor in lowering levels of economic inequality.

Recent years have seen increased policy and academic focus on the potential causes and effects of rising market power on the labor share—the share of labor compensation (wages) as a proportion of total production—and in turn, on levels of inequality in developed nations. A possible decline of the labor share is not just an academic puzzle—it reflects a fundamental aspect of the way that the gains of productivity and progress are shared between individuals in modern society. This measure can be aggregated from the firm level to an industry and country level in a way that reflects the systematic shares of labor vs capital over time, the ‘winners and losers’ of society.

Some studies conclude that global factors are the principal contributing factors leading to the decline in the labor share in most of the developed world. While different voices within this debate emphasize different economic mechanisms in their analyses—such as technological advances and global trade, the rise of ‘superstar’ firms, or increasing global market power—all agree that the factors behind the decline of the labor share are not specific to any one country or jurisdiction.

In contrast, other studies point to local drivers of the decline in the labor share—meaning, a country’s or region’s idiosyncratic factors, such as national and regional differences in the regulation of labor and product market. Generally speaking, these studies argue that the decline in the labor share may not be a global phenomenon, and is overstated in many developed countries. They argue that such global claims are the result of inappropriate cross-country comparisons.

Figure 1 presents changes in national labor share in selected countries. The labor share measure is based on the EU KLEMS project, which provides a database on measures of economic growth, productivity, employment, capital formation, and technological change at the industry level for all European Union member states, Japan, and the US. What seems to be apparent from Figure 1 is that while the labor share has trended downwards for the US and Canada over 1995-2005, the trend is less uniform in other countries, with the labor share remaining constant in some countries and rising in others.

Figure 1: Country-Aggregated Labor Share Comparisons

What can explain this difference in the labor share trends across these developed countries? While existing studies have identified a range of factors, they have largely overlooked the role that competition policy could have in shaping market dynamics and controlling market power in different economies.

In a recent working paper co-authored with Carola Casti, Christopher Decker, and Ariel Ezrachi, we examine whether, and how, competition policy might reflect in changes in the labor share, given its potential ability to control market power. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that changes in the labor share in developed countries—shown in Figure 1—may, in part, be influenced by the relative effectiveness of the competition policy enacted in that country. In other words, we explore the question of whether competition policies that are more effective in controlling market power are also associated with a higher labor share.

If it is the case that competition policy and the labor share are related in a positive way, then this suggests that effective competition policy could generate positive effects beyond its traditional efficiency goals and result in labor receiving a higher share of welfare gains. These possible distributional effects of competition policy are potentially significant, given that labor income is more evenly distributed across households than capital income—meaning, more households, particularly lower income households, derive most of their income from wages than from capital ownership. In short, effective competition policy may be an important contributor to lowering levels of economic inequality in the long run through the changes in the labor share that accompany its efforts to control market power.

The Link Between Profits and the Labor Share

The decline of the labor share is argued to be a direct consequence of the rise of markups and increases in concentration and associated monopoly rents. Accurately estimating markups is a complex econometric task that requires the use of strong assumptions, or the estimation of production functions using firm level data to retrieve elasticities. However, since profitrates and concentration levels are correlated with markups, the link between these measures and the labor share offers a workable way around these problems.

Figure 2 shows how average profits and the labor share are related in our sample. Each red dot represents one observation of the labor share in our sample of 22 industries in each of the 12 OECD countries we studied (Canada, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States) over the period between 1995-2005. A negative correlation between average profit in the industry and the labor share estimates is shown by the red line, implying that the higher the average profit the lower the labor share.

Figure 2: Labor-Capital Share and Average Profits by Industry

Competition Policy and Changes in the Labor Share

As described above, the main contribution of our working paper is to focus on how competition laws might impact the labor share. Specifically, we empirically investigate whether there is any association between the competition policy applied in a specific jurisdiction—the scope of competition law, enforcement, and institutions—and observed changes in the labor share in that jurisdiction. Our sample of 12 OECD countries captures both cross country and cross regional effects. In addition, we test whether the interaction between competition law and the labor share is affected by various ‘local’ factors specific to each country, such as the degree of unionization, other forms of labor protections, or product market regulations.

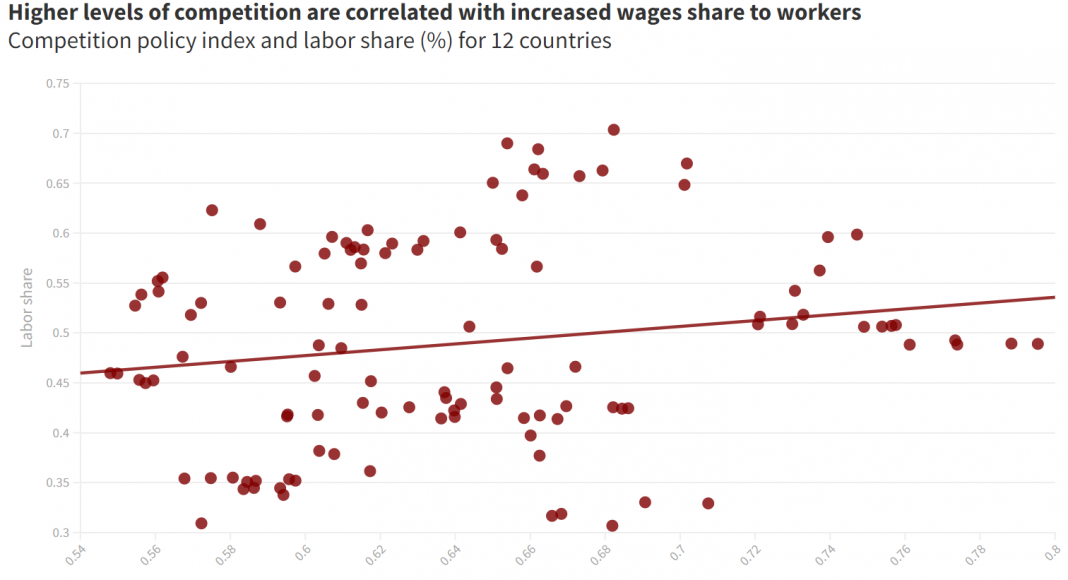

Figure 3 captures the simple correlation between the Competition Policy Index (CPI) and the labor share. It shows a generally positive trend: higher values of the CPI (which implies more effective competition law) are associated with higher labor shares in the national level.

Figure 3: Competition Policy Index and the Labor Share

To further investigate this relationship, we use an econometric model to isolate the effect of competition policy (as proxied by the CPI) on the labor share. This model controls for the effects of historical differences between countries and industries, global trends and other factors associated with changes in the labor share identified in previous work.

Our results confirm the trends shown in Figure 3 and suggest a positive and statistically significant link between effective competition policy and a higher labor share. This positive relationship is robust to several specifications of the model and controls, both at the industry level (e.g., import penetration) and at country level (e.g., product market regulation). To address the risk that we have omitted other important variables from our model that could explain observed changes in the labor share, we apply additional econometric tests to specifically isolate the effects of competition laws.

Digging deeper into the data, we also test whether the levels of labor protection and labor bargaining power impact the interaction between competition policy and changes in the labor share. This is based on the intuition that when strong labor institutions are in place, employees can use their bargaining power in labor markets to call for higher wages. However, in places where the bargaining power of labor is weak, or inadequate employment protections are in place, this provides scope for firms with market power to increase profits and markups by lowering wages, and the task falls to competition policy alone to constrain the implications of market power.

Our results suggest that there is an interaction between competition policy (which focuses on prices in the product markets), labor policies, and institutions (such as the extent of unionization), all of which jointly contribute to the competitive environment, labor market outcomes, and macroeconomic trends. In the context of inequality, this suggests that competition policy will have a greater role to play in reducing economic inequality in jurisdictions with weak labor laws or limited labor bargaining power.

Lastly, we explore whether there were any differences for countries whose competition laws closely resemble the EU legal text compared to countries whose competition regimes borrows from the US antitrust law’s text. Here, we find that the interaction term between the CPI and EU text is positive and statistically significant, suggesting that countries that adopted EU-style competition laws were more successful (or less unsuccessful) compared to countries that adopted US-style antitrust laws, such as Canada and Japan. However, caution should be exercised in relying too heavily on this conclusion, and more work is needed, using other proxies to capture the uniqueness of the US and EU competition models.

Our paper offers new insights to the debate introduced above the relative importance of ‘global’ versus ‘local’ factors in explaining observed changes in the labor share. This is because under the pure global factors argument, we would not expect to see significant differences in the effects of competition policy between countries or regions. In other words, if the claim is that market power is on the rise globally and has been largely driven by the innovation and efficiencies—for instance, the superstar firms hypothesis—than the individual competition laws of particular countries are likely to have played only a minor or no part in changes in market dynamics and in the labor share.

However, if rising market power is not a clear global trend, or not one of parallel significance, this focuses attention on other ‘local’ factors which could explain the rise of markups and decline of the labor share in specific countries. In short, it suggests that the reason why some countries have not experienced a significant decline in the labor share is because they performed (slightly) better than others in controlling market power and anti-competitive practices.

Final Remarks

We find that the effectiveness of competition policy is positively associated with the labor share. When more effective polices are in place, the labor share is higher. These results hold over several specifications and econometric models.

Our results suggest that the specific idiosyncratic features of a country’s competition law appear to be relevant when considering the interaction between competition policy and the labor share. For instance, since EU competition law is broadly considered to have a different philosophical structure and greater appetite for enforcement than the US, which supports the notion that the less active antitrust law enforcement could be a ‘local’ factor that has contributed to the observed decline in the labor share in the US. The results also reinforce the importance of considering other local factors, particularly forces that shape the levels of labor protection and labor bargaining power, when examining changes in the labor share.

Overall, our results suggest that there may be a causal link between competition policy and the labor share and, more broadly, distributional outcomes. However, more work is needed to confirm this result. We recognize, for example, that there is a need to account for the fact that competition policy is, in fact, not merely a corrective tool for markets but, at the same time, may shape or correlate with the quality of a country’s economic institutions more generally (such as central banks). In addition, our analysis is based on aggregated industry data, which does not allow us to account for labor shares among firms within the same industry. We believe that while growing evidence of rising global markups aligned with previous work on the labor share (and its association with trade and technological developments), there is still scope for local factors—in particular the effectiveness of local competition laws—to explain some of the inconsistencies and variations observed across countries.

Rising economic inequality presents society with unprecedented challenges. Direct instruments designed to address these worrying trends have often under performed. In this reality, competition law may serve as a valuable complementary instrument, which shapes distributional outcomes. It can do so as part of its mandate to protect free market rivalry. As we illustrate in our recent research, that market rivalry also has the potential to promote economic equality and stability via its effects on the labor share.

Disclosure: This research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust in the UK as part of a larger project on Competition Law and Inequality at Oxford University.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.