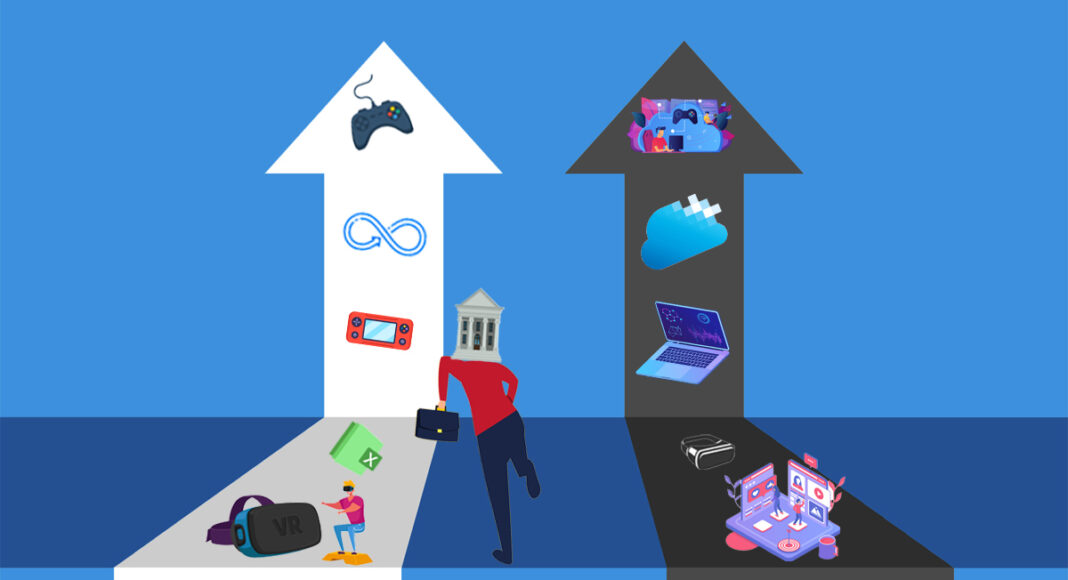

Joshua Gray and Cristian Santesteban argue that the Federal Trade Commission’s focus in Meta-Within and Microsoft-Activision on narrow markets like VR fitness apps and consoles missed the boat on the real competition issue: the threat to future competition in nascent markets like VR platforms and cloud gaming.

The Federal Trade Commission has been the subject of much criticism for challenging the Meta and Microsoft mergers, partly based on “dead-letter doctrine.” Critics argue the FTC’s recent losses stem from outdated precedents or insufficient evidence. We do not evaluate the merits of those critiques here; instead, we argue the FTC invited this critique by not fully focusing on the key competition issues: those tied to critical technological transitions.

The Meta-Within merger decision primarily turned on the state of competition in a market for “dedicated virtual reality (VR) fitness apps.” The FTC argued that the merger would stifle competition by allowing Meta to absorb the leading VR fitness app rather than developing its own. In Microsoft-Activision, the FTC did argue about future competition in a nascent area, cloud gaming, but its point was largely obscured amid extensive debates over Microsoft’s post-merger favoritism toward its own Xbox consoles. The problem for the FTC is that neither VR apps nor game consoles are the central competition concerns in these cases.

Meta was not just acquiring another fitness app; it was targeting a key segment of the emerging VR platform market. Microsoft was not just acquiring a set of video games for its decades-old technological platform; it was strategically positioning itself in a shifting tech landscape toward cloud-based streaming. Indeed, both deals aimed to acquire loyal and engaged users at pivotal technological junctures. The FTC is aware of the problem of a leading technology firm acquiring its way into a dominant position in the next generation of technology. In Microsoft-Activision, the agency highlighted in its pleading that “[t]he acquisition of new users, content, and developers each feed into one another, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that entrenches the company’s early lead.” In another case, the agency seeks to unwind Meta’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp because, in retrospect, they appear to be clear strategic acts of monopolization in mobile “social networking tools.” Similarly, the agency likely regrets approving Google’s purchase of Waze in 2013, mistaking it for just another map app rather than a unique “social navigation tool” with a rapidly growing and engaged set of users in the then-emergent mobile space.

Acquisitions of this type should have been a primary focus of antitrust merger policy since the historic monopolization case US v. Microsoft in the late 1990s. A common argument by the most ardent Microsoft defenders was that its conduct, designed to “cut off its [Netscape’s] air supply,” was not anticompetitive because Microsoft could have simply acquired Netscape instead and the Agencies wouldn’t have objected. While this should have never been a strong defense of Microsoft’s conduct, it should have raised flags about antitrust policy.

In bringing these merger challenges, the FTC should have clearly argued that Meta and Microsoft’s acquisitions risk stifling competition in a nascent technological realm, akin to a hypothetical Microsoft-Netscape deal in 1996. This framing entails protection of a competitive process at technological transitions but leaves open how to articulate in detail the threatened harm.

A better framed FTC argument could have yielded more meaningful results. Had the FTC won, the law could have moved toward greater protection of competition at critical technological junctures. A loss would have ramped up pressure on Congress to amend Section 7, acknowledging the growing evidence of the courts’ limitations in cases involving technological transitions. Instead, we are now in a muddle.

Microsoft-Activision

Microsoft aims to acquire Activision in an industry shifting from consoles, to multi-game device-agnostic subscriptions, to more recently streaming directly from the cloud. Despite existing challenges of streaming like latency in fast-paced games, Microsoft’s decision to spend $69 billion to acquire Activision positions it to dominate this technological transition.

Activision’s prized asset, Call of Duty, has a large, dedicated fan base. To gain EU and UK regulatory approval for the acquisition, Microsoft has offered remedies focused solely on cloud gaming: royalty-free licenses in the European Union and streaming rights to Ubisoft in the United Kingdom. These remedies ignore game-download subscriptions. Microsoft will have the ability and incentive to restrict rival access to these games in game-download subscriptions and become the sole multi-game download subscription provider with Activision games. Judge Jacqueline Corely acknowledged as much: “The Court accepts for preliminary injunction purposes it is likely Call of Duty will be offered on Game Pass, and not offered on rival subscription services” (emphasis supplied). While the remedies across the Atlantic have removed Microsoft’s ability to retain exclusivity in cloud streaming, Microsoft will still in practice be able to monopolize Activision’s loyal fanbase through its download version of Game Pass subscriptions.

By holding exclusivity in game-download subscriptions, Microsoft is well-placed to seamlessly transition its loyal Activision users to cloud streaming through bundled offerings (that include both game-download and streaming) as cloud-based gaming becomes more important. This strategy not only locks in a dedicated user base but also elevates customer acquisition costs for competitors like Nintendo. It becomes much harder to entice users to stream Activision games on non-Microsoft platforms if Microsoft is the only platform also offering those games for download subscriptions. This seems to be the most natural reading of Microsoft’s internal documents stating that the Activision acquisition would help Microsoft to construct a “moat” around its gaming business, empowered by its cloud infrastructure that is unmatched by its gaming competitors.

Because Microsoft’s Xbox trails by a wide margin Sony’s PlayStation in console popularity, Microsoft doesn’t pose a significant “moat” issue in this market segment. Judge Corely’s opinion, however, fixates on console foreclosure risks, largely overlooking the future of cloud streaming competition. This narrow focus is at odds with the EU Directorate-General for Competition, which identified multi-game subscriptions—not consoles—as the primary competition concern.

Turning to streaming, the FTC’s economic expert Professor Robin Lee testified “the lack of really good data for [streaming] services made it very difficult to perform something that I would view as reliable that’s quantitative for these markets.” This candid statement underscores the inherent challenges confronting the FTC or any other plaintiff in assessing nascent industries. However, this is not a good reason to dodge the main competition concern by focusing on less contentious areas like console foreclosure—particularly when Microsoft, lacking console dominance, has committed to licensing Activision games to Sony for a decade.

Given the importance of download subscriptions as a gateway to a streaming future, one would have expected an extensive analysis on the competitive impact of Activision exclusivity in Microsoft’s subscription service. Instead, Corely dismisses the concern of Microsoft’s exclusive access to Activision games in download subscriptions and buys into Microsoft’s vision that Activision would not have even licensed its games for subscriptions in the but-for world: “Activision believes that it is not in its financial interest [to license subscription services] because it would cannibalize individual sales.” While Activision’s reluctance may be genuine, it overlooks the inevitability of change, especially as subscriptions continue to gain traction. In such a landscape, Activision would have to adapt, just as it in fact did by agreeing to sell itself to Microsoft.

In summary, the court’s focus on the almost moot console market overshadowed how Activision’s likely exclusivity in Microsoft’s subscription service will set the stage for Microsoft’s dominance in cloud streaming—EU and UK remedies notwithstanding. We are thus left with the disappointing sense that the FTC and merging parties never engaged on the most pressing issue in the case: the merger’s effect on competition during a critical technological transition.

Meta-Within

Meta-Within narrowly focused on VR fitness apps, overlooking the broader and competitively more significant issue of VR platform competition.

Professor Steven Salop previously presented a compelling argument that the FTC should have alleged an alternative theory that the acquisition would allow Meta to foreclose VR competitors, including Apple. We cannot know the FTC’s reasons for not making this allegation, but it may have perceived great difficulty in arguing a foreclosure theory in the still developing VR platform landscape.

Following Salop, Judge Edward Davila’s fact-finding in this case could have supported the view that Meta’s decision to acquire Within’s Supernatural was suspect for VR platform competition. Davila recognized that fitness apps have unique and valuable users (“on average an older person, on average more women”) that could influence the adoption of VR technology and help VR to become the next general computing platform.

Given his findings, Davila could have questioned why Meta wanted to own the leading VR fitness app rather than continue funding third-party app development. As a VR platform, Meta’s incentives would appear to be aligned with the presence of many competitive and differentiated apps as this attracts more users to the platform.

Yet, after funding third-party app development for years, Meta decided that it wanted to own Supernatural. Why? This is an open question, and it would have been better for the development of the law if Davila had attempted to answer it. However, because he evidently believed that Meta’s VR platform ambitions were either irrelevant to, or exculpatory under, the FTC’s potential competition claim, Davila saw no reason to question the rationale for the acquisition in light of Meta’s sponsorship of other third-party apps.

The potential competition arguments distracted from the central issues of the case. The focus on whether Meta would enter the fitness app market misses the point, which is that Meta should not be allowed to buy a potentially key app that distorts future competition in VR platforms. If the FTC had hoped for a blanket ban on an incumbent’s ability to buy apps on its own platform, a general rule with which we do not agree, this is certainly not what the FTC got. Instead, the ruling is a setback for the law as the opinion gives entirely too much deference to the merging parties’ strategy documents. Davila’s decision not only doesn’t speak to the relevant competition concerns but also places too much weight on record evidence of business planning and the acquirer’s in-house capability as an entrant. If the buyer’s documents say it won’t enter itself, it can buy whatever it wants. Antitrust counsel will advise their clients to write their defenses into their business strategy documents to preserve the client’s freedom to acquire as it pleases.

Davila’s opinion also glosses over the competitive implications of Meta’s acquisition in the context of Apple’s new rival VR headset: “Meta employees were expecting Apple to ‘lock in’ VR fitness content to be exclusive with Apple’s VR hardware.” Further, his opinion refused to evaluate whether Meta’s acquisition of another less competitively problematic fitness app (e.g., FitXR) could have been “an available feasible means” of entry. Finally, the judge never even broached the possibility of an alternative buyer of Supernatural as a more competitively palatable alternative.

Acquisitions of promising new startups by dominant platforms is not new, and we can be certain these issues will recur. Often, the buyer that pays the largest premium for a fast-growing asset is the buyer with the most to lose if another firm is the buyer. Google bought Waze and kept it away from Apple, a preemptive transaction that may have delayed or ended competition to Google Maps. (Imagine a world in which Apple’s acquisition of Waze would have resulted in the two most used iPhone apps being Google Search and Apple Waze rather than Google Search and Google Maps.) Meta-Within missed a chance to advance legal principles overdue since Google-Waze.

Conclusion

We commend the FTC for bringing actions in industries facing critical technological transitions; however, the agency erred in its narrow focus on fitness apps and gaming consoles. Only by zeroing in on future competitive harms in the next generation technology (VR platforms and game streaming) can the FTC force courts to address head-on these important issues.

We know from the past 20-plus years that leading technology firms can distort competition for the market by acquiring their way onto the winner’s podium in the next iteration of their businesses. This can negatively skew outcomes, reshaping industry leaders and market structure.

The challenge for the FTC and other antitrust agencies is how and where to draw a viable threshold under the incipiency standard of Section 7 of the Clayton Act that bars acquisitions where “the effect … may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.” Regrettably, Microsoft-Activision and Meta-Within leave us no closer to resolving this pressing question.

Author Disclosures:

Joshua Gray has counseled clients about potential antitrust claims against several global technology firms, including Google. However, he did not represent any of the parties involved in the cases mentioned in this article. After more than a decade of working on antitrust M&A both at the FTC and in private practice, his practice transitioned to entirely conducting litigation after 2012.

In the last two years, with his consulting company RedPeak Economics, Cristian Santesteban has consulted for law firms doing preliminary investigations of antitrust issues involving Google. He has not done any consulting work relating to Microsoft-Activision, Meta-Within, or U.S. v Microsoft.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.