Spotify is gaining power over podcast distribution by either buying production directly or striking exclusive deals, as it did with Rogan. Once it has gatekeeping power over distribution and a large ad targeting business, it will be able to control which podcasts get access to listeners, and who can monetize them.

A few days ago, audio streaming giant Spotify announced a deal with podcast king Joe Rogan, with the Wall Street Journal reporting that Rogan will be paid more than $100 million over several years in return for making his insanely popular show exclusive to the Spotify service.

This is huge news.

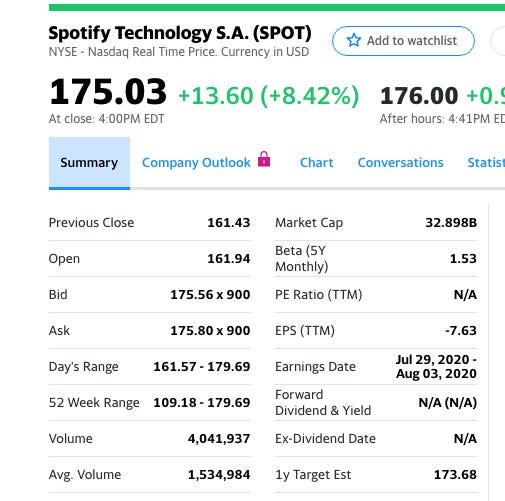

Investors were pleased; Spotify’s stock was up 8.42 percent, which is roughly $2.5 billion, or twenty-five times what Rogan will be paid. It was up another 7 percent the following day. From the perspective of someone who appreciates independent voices and an independent press, however, I’m concerned.

Back in February, after Spotify bought the podcast production company of Bill Simmons with its bevy of popular content, I wrote up how Spotify is trying to monopolize the podcasting market.

To explain Spotify’s strategy, I analogized the current podcast market to the web in the mid-2000s. As the web used to be, today podcasting is an open market, with advertising, podcasting, and distribution mostly separated from one another.

Distribution happens through an open standard called RSS, and there’s very little behavioral ad targeting. I’m asked on fun weird podcasts all the time; podcasting feels like the web prior to the roll-up of power by Google and Facebook, with a lot of new voices, some very successful and most marginal, but quite authentic.

So what is Spotify trying to do?

First, Spotify is gaining power over podcast distribution by forcing customers to use its app to listen to must-have content, by either buying production directly or striking exclusive deals, as it did with Rogan. This is a tying or bundling strategy. Once Spotify has a gatekeeping power over distribution, it can eliminate the open standard rival RSS, and control which podcasts get access to listeners.

The final stage is monetization through data collection and ad targeting. Once Spotify has gatekeeping power over distribution and a large ad targeting business, it will also be able to control who can monetize podcasts, because advertisers will increasingly just want to hit specific audience members, as opposed to advertise on specific shows.

As I wrote in February:

“No advertiser will care if you’re a listener of Joe Rogan or Bill Simmons, only that you are a 34 year old male with a certain income reachable in thirty forty different audio slots, which can then all go in an auction. Or even if they do care, competitive ad networks who offer the service you want will probably die. Then, just as the New York Times content becomes far less important online because Google can just find you that New York Times reader through another publisher outlet or Google’s own properties, the actual podcast becomes commodified, because all that matters is the listener data combined with the ad slots, not the show against which those ad slots are sold. This is another complicated way of saying the people who do the work of making and distributing a show don’t get the benefit from the work they do.”

Spotify got this power through acquisitions. I noted that “from 2014 to 2020, Spotify bought 15 companies, companies that build everything from data analytics to music and audio production tools to audio ad tools to licensing platforms, and podcasting networks. These companies included the Echo Nest (2014), Seed Scientific (2015), CrowdAlbum (2016), Sonalytic (2017), MightyTV (2017), Mediachain (2017), Niland (2017), SoundTrap (2017), Loudr (2018), Gimlet (2019), Anchor (2019), SoundBetter (2019), Parkast (2019), and now The Ringer (2020).”

This contract with Joe Rogan isn’t a purchase, but it’s an exclusive deal or a bundle. In antitrust parlance, I can see this kind of arrangement being treated as either an exclusive dealing practice or a tying/bundling practice.

Antitrust is a bizarre legal area, with a lot of it structured through court-made law instead of statute, and many of the practices under its purview blurring into one another. Such is the case here.

The case law on bundling/tying is pretty strong; enforcers have the ability to block those with market power from tying products together for anti-competitive purposes. The trick for tying is that those doing the tying can argue that two products put together are simply being integrated into something new. If you take a mouse, a keyboard, a monitor, and a computer, and combine them all into a new product called a laptop, that’s integration, not an anti-competitive practice.

Exclusive dealing case law is much weaker. While exclusive dealing arrangements can be illegal, in practice courts tend to be quite permissive. The rationale for allowing such restraints is that they have what is called pro-competitive benefits.

If you take a mouse, a keyboard, a monitor, and a computer, and combine them all into a new product called a laptop, that’s integration, not an anti-competitive practice

Spotify might, for instance, be boosting Rogan’s reach to new listeners, and Rogan could be improving Spotify’s service by doing Spotify-specific snippets. So anything lost by rival distributors who can’t broadcast Rogan or by consumers who wish to use a different app other than Spotify is counterbalanced by that benefit.

What’s interesting, with either tying or exclusive dealing, is that Rogan has made it clear that there are likely to be few consumer benefits. He promised his listeners that “it will be the exact same show. I am not going to be an employee of Spotify. We’re going to be working with the same crew doing the exact same show.” The only difference is consumers won’t be able to get the Rogan show through other channels. It’s purely a restraint of trade. In other words, there’s literally no justification for this deal as anything but a payoff to Rogan from an aspiring monopolist who seeks to force Rogan listeners to use the Spotify app.

It’s a leverage of Rogan’s legal monopoly over his own copyrighted material to create a distribution monopoly, which was one of the legal issues at stake in the 1948 Paramount decrees case that ended the monopolistic Hollywood studio system.

Unlike nearly everywhere else in the media space, podcasting is a good open space with a lot of competition and authentic voices

Now, I can imagine the argument that targeted advertising brings some sort of benefit I’m leaving out, that Rogan’s ad inventory will bring scale for podcast monetization. But the downside to consumers is quite obvious, while no one has been able to show that targeted advertising is a net positive.

Spotify isn’t the only bad actor here. The corporation is under heavy pressure from Amazon, Apple, and Google, all of whom have interests in the streaming music and podcast business, and all of whom can cross-subsidize with other streams of revenue. They also have gatekeeping control over Spotify through app stores. Here’s Spotify protesting to one of Congress’s Antitrust Subcommittees how Apple uses its bottleneck power:

“Apple operates a platform that, for over a billion people around the world, is the gateway to the internet. Apple is both the owner of the iOS platform and the App Store—and a competitor to services like Spotify. In theory, this is fine. But in Apple’s case, they continue to give themselves an unfair advantage at every turn.”

If you put Spotify where Apple is, and change a few words so that this describes streaming instead of apps, this sentence describes Spotify’s strategy. They want to become the gateway to streaming, so they can tax the ecosystem. (It’s admittedly a bit more complex since Spotify is indirectly taxing via ad targeting and has to pay for music rights whereas Apple is directly taxing via an app store fee, but the power dynamics are similar.)

Regardless, right now, unlike nearly everywhere else in the media space, podcasting is a good open space with a lot of competition and authentic voices. Regulators and policymakers can step in to protect it. They can still undo the merger of Spotify and The Ringer, and they can certainly initiate an investigation of Spotify’s exclusive strategy as a possible set of attempts to monopolize an industry. Hopefully members of Congress will start asking questions.

This column originally appeared in BIG, Stoller’s newsletter on the politics of monopoly. You can subscribe here.