In the second installment of our four-part series about the history of antitrust language in American political discourse, we review the evolution of economic language related to competition in all Democratic and Republican platforms from 1876 to 2016.

This is the second installment in our series, “140 Years of Antitrust: Are Brandeisian Pro-Competition and Anti-Monopoly Sentiments Coming Back into the Political Discourse?” The first installment can be found here.

“A new commitment to promote competition, address excessive concentration and the abuse of economic power, and reinvigorating antitrust laws and enforcement”.

This strong language was released last week, without much attention, by the Hillary Clinton campaign in a factsheet that detailed the economic policy proposals Clinton intends to promote if she is elected president.((“Hillary Clinton’s Vision for an Economy Where our Businesses, our Workers, and Our Consumers Grow and Prosper Together,” October 2016.))

Last week, the ProMarket blog launched a new short series of posts on the history of antitrust and competition language in political discourse. This series is a response to signs of a revival of these issues ahead of the 2016 election. Clinton’s policy brief may be the strongest signal yet that the potential importance of antitrust and competition issues may increase in the next few years.

In her brief, Clinton addresses some very detailed ideas about antitrust that have been absent from political discourse for decades. Among the issues she raises are: “Appoint strong leadership at our antitrust agencies,” “Aggressively enforce and strengthen merger reviews as well as our antitrust laws and guidelines,” “Prevent the inappropriate exploitation of excessive market power where it already exists,” “Ensure post-merger retrospective reviews, and transparency,” and “Make promoting competition a goal of agencies across the Federal government–and more broadly.”

In this post, we aim to review the evolution of economic language related to competition in all Democratic and Republican platforms from 1876 to 2016. We use platform texts archived at The Presidency Project of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

We used an online tool for automatic word analysis but context is extremely important (e.g. the word “trust” can mean both a business structure and confidence; or “regulation” can also relate to family planning), so in some cases we also performed human analysis. Because some of the terms can be mentioned in conflicting contexts, the data should be treated as indicative of the discussion of these terms and not as an indication of support or criticism. This is especially the case in later election cycles, as the discussion evolved.

In this installment, we will go into detail into the platforms, analyzing mentions of competition. In the next part, the terms analyzed will be antitrust and concentration of power.

Competition

The last decades of the 19th century in the U.S., following the end of the Civil War, the abolition of slavery, a higher influx of immigrants, and the Industrial Revolution, saw rapid growth, led by a shift from agriculture to manufacturing. Wages in many parts of the U.S. rose significantly, but so did inequality. This era also led to the creation of huge business enterprises–trusts. The businesspeople who controlled these trusts were active in finance, real estate, steel, copper, coal, retail, oil, railroads, and other areas.

Trusts became so apparent and evident that in 1890 Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act, which was the first federal competition statute. The second major legislation to promote competition was the Clayton Act of 1914 that expanded and added substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime. The third was the 1933 Banking Act (better known as the Glass-Steagall Act), aimed at banking.

During these years, the term “competition” was mentioned a few times in Democratic and Republican platforms, but while Democrats associated competition with the domestic economy, Republicans focused on competition coming from outside the country:

Democratic platform, 1888 (Benjamin Harrison v. Grover Cleveland):

“Judged by Democratic principles, the interests of the people are betrayed, when, by unnecessary taxation, trusts and combinations are permitted and fostered, which, while unduly enriching the few that combine, rob the body of our citizens by depriving them of the benefits of natural competition.”

Republican platform, 1892: (Grover Cleveland v. Benjamin Harrison):

“We believe that all articles which cannot be produced in the United States, except luxuries, should be admitted free of duty, and that on all imports coming into competition with the products of American labor, there should be levied duties equal to the difference between wages abroad and at home.”

It was not until 1900 that the Republicans mentioned competition in a domestic sense:

Republican platform, 19

00 (William McKinley v. William Jennings Bryan):“…we condemn all conspiracies and combinations intended to restrict business, to create monopolies, to limit production. or to control prices; and favor such legislation as will effectively restrain and prevent all such abuses, protect and promote competition and secure the rights of producers, laborers, and all who are engaged in industry and commerce.”

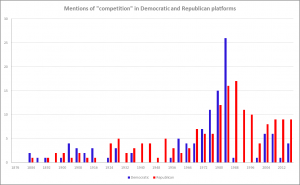

Nevertheless, the term was not mentioned in any significant way in either the Democratic or Republican platforms until the late 1960s–some 80 years after the Sherman Antitrust Act was passed. Between 1876 and 1964, no platform mentioned competition more than 5 times.

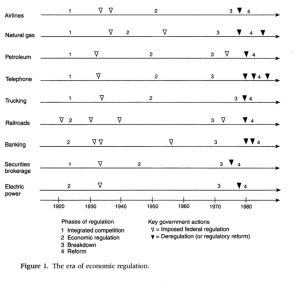

In his 1996 book Contrived Competition: Regulation and Deregulation in America, Harvard economist Richard Vietor laid the groundwork for the undercurrents that shaped the regulatory environment from the beginning of the 20th century.((Richard Vietor, “Contrived Competition: Regulation and Deregulation.” Belknap Press, 1996.))

The era of regulation, he wrote, is framed by the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Stagflation of the 1970s.

The near collapse of the American economy in the 1930s was mainly blamed on the failure of competition. The type of competitiveness that prevailed in the decades preceding the Depression resulted in trusts, pyramids, “corporatism,” and big business. And what allowed this to happen was the consensus of state/local regulation and the near absence of the federal government from the regulatory environment. This reckoning led to a new consensus that was prevalent mainly during the Franklin D. Roosevelt era: the government, not markets, would restore the public’s confidence. That consensus led to a wave of regulatory legislation by the federal government, especially during the 1930s.

The person FDR trusted with achieving these goals was Thurman Arnold, a lawyer who later became a professor at Yale Law School. In March 1938, FDR put him in charge of the Antitrust Division in the Department of Justice, a job he kept until 1943.

By 1942, during Arnold’s tenure, the Antitrust Division’s lawyer headcount grew dramatically: from 15 to 583. “Arnold,” Harvard law professor Einer Elhauge recently told ProMarket, “also made antitrust enforcement far more systematic and focused. Arnold deliberately used antitrust enforcement as a form of economic policy. He targeted industries that he thought were inefficient in a way that hampered economic growth. He also used multiple simultaneous lawsuits in each selected industry to thoroughly restore free competition at each stage of the industrial process. His strategy was ‘to hit hard, hit everyone and hit them all at once.’”

Subsequently, Arnold brought 44 percent of all the antitrust cases that were brought in the first 53 years of antitrust laws. This policy found its way into both parties’ platforms:

Democratic platform, 1932 (Herbert Hoover v. Franklin D. Roosevelt):

“We advocate strengthening and impartial enforcement of the anti-trust laws, to prevent monopoly and unfair trade practices, and revision thereof for the better protection of labor and the small producer and distributor.”

Democratic platform, 1936 (Alfred M. Landon v. Franklin D. Roosevelt):

“We pledge vigorously and fearlessly to enforce the criminal and civil provisions of the existing anti-trust laws, and to the extent that their effectiveness has been weakened by new corporate devices or judicial construction, we propose by law to restore their efficacy in stamping out monopolistic practices and the concentration of economic power.”

Democratic platform, 1940 (Wendell L. Willkie v. Franklin D. Roosevelt):

“We have enforced the anti-trust laws more vigorously than at any time in our history, thus affording the maximum protection to the competitive system.”

The Republican Party stayed largely silent on the subject until the 1940 election, when the platform reminded the public that the first antitrust law, the Sherman Antitrust Act, was enacted during a Republican presidency, blamed FDR’s New Deal policy for creating monopolies, and criticized Arnold’s tactics:

Republican platform, 1940 (Wendell L. Willkie v. Franklin D. Roosevelt):

“Since the passage of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act by the Republican party we have consistently fought to preserve free competition with regulation to prevent abuse. New Deal policy fosters Government monopoly, restricts production, and fixes prices. We shall enforce anti-trust legislation without prejudice or discrimination. We condemn the use or threatened use of criminal indictments to obtain through consent decrees objectives not contemplated by law.”

The new era of regulation coincided with a prolonged period of prosperity, as expressed in the table below, which Vietor took from The Economic Report of the President for 1973((Economic Report of the President, 1973.)) and 1991((Economic Report of the President, 1991.)):

But by the late 1960s, the era of quick growth all but wore out. Two major international developments and one domestic development had a significant influence on both parties’ attitude toward competition and regulation. The first international event was the 1970s oil price shock, which brought the price per barrel from around $20 in 1973 to about $115 in 1980((Crude Oil Prices – 70 Year Historical Chart.)) (Prices then decreased, but remained high until late 1985). The second international issue was the developing and increasing balance of trade deficits that began in the mid-1970s.((United States Balance of Trade, 1950-2016.))

The major domestic development was an increase in economic studies that favored and pushed for deregulation. One of the major papers on deregulation was published in 1971 by Nobel Laureate and University of Chicago professor George Stigler (The Theory of Economic Regulation)((George Stigler, The Theory of Economic Regulation, 2 Bell Journal of Economics 3 (1971).)), in which he developed the idea of regulatory capture–when regulation is highly influenced by the industry and corporations it regulates for their own needs. Another was the 1970 book The Economics of Regulation by Cornell University’s Alfred Kahn, who was also known as the “father of airline deregulation.”

The result was a wave of federal deregulation that took place mostly in the late 1970s, during the Carter administration. In his book, Vietor provided a chart that describes the waves of regulation and then deregulation:

On the Republican side, mentions of competition started picking up in 1972 and peaked in 1984.

Republican platform, 1972 (Richard Nixon v. George McGovern):

“We will press on for greater competition in our economy. The energetic antitrust program of the past four years demonstrates our commitment to free competition as our basic policy. The Antitrust Division has moved decisively to invalidate those “conglomerate” mergers which stifle competition and discourage economic concentration.”

This specific Republican platform language on competition and antitrust before the 1972 elections can offer some cynical perspective on the possible disconnect between political rhetoric and action.

The Watergate affair revealed some interesting dynamics and corrupt deals conducted by the Nixon administration that were directly tied to antirust.((For further reading on Watergate, see here.))

The tapes and investigation revealed that the Nixon administration used or threatened to use antitrust action to advance their political interests. In 1969, International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) acquired three smaller corporations, prompting the US Justice Department to file suits against ITT, charging that the mergers violated antitrust laws. Yet two years later, the Justice Department reached a deal with ITT to drop the government’s antitrust lawsuit. The “consent decree” allowed ITT to keep some of the firms it had attempted to merge with. Some observers noted that ITT was allowed to merge with the firms that were relatively profitable, and dispose of the companies that would lose money for the corporation. Later it was revealed that in order to influence the decision of the administration, ITT agreed to secretly give $400,000 to finance the GOP’s 1972 national convention in San Diego.((Walter Pincus and George Lardner Jr., “Nixon Hoped Antitrust Threat Would Sway Network Coverage.” Washington Post, 1997.))

Another use of antitrust as a threat for political ends was revealed in 1997 when conversations held in the Oval Office in 1971 were transcribed for the first time. In the transcriptions, Nixon is quoted as threatening to use antitrust actions against the three major television networks in order to influence their news coverage: “If the threat of screwing them is going to help us more with their programming than doing it, then keep the threat,” Nixon told a White House aide.

Republican platform, 1976 (Jimmy Carter v. Gerald Ford):

“The Republican Party believes in and endorses the concept that the American economy is traditionally dependent upon fair competition in the marketplace. To assure fair competition, antitrust laws must treat all segments of the economy equally.”

Republican platform, 1980 (Ronald Reagan v. Jimmy Carter):

“All working men and women of America have much to gain from economic growth and a healthy business environment. It enhances their bargaining position by fostering competition among potential employers to provide more attractive working conditions, better retirement and health benefits, higher wages and salaries, and generally improving job security.”

Also in 1980, when mentioning competition, the Republican platform started shifting its focus to foreign trade, especially in relation to cars imported from Japan and oil from the OPEC countries, and the ways in which regulation hurts competition. This continued into 1984:

Republican platform, 1980 (Ronald Reagan v. Jimmy Carter):

- “As we

meet in Detroit, this Party takes special notice that among the hardest hit have been the automotive workers whose jobs are now targeted by aggressive foreign competition.”- “The Republican Party will consider appropriate measures necessary to restore equal and fair competition between ourselves and our trading partners.”

- “Fairness to the consumer, like fairness to the employer and the worker, requires that government perform certain limited functions and enforce certain safeguards to ensure that equity, free competition, and safety exist in the free market economy. However, government action is not itself the solution to consumer problems; in fact, it has become in large measure a part of the problem. By consistent enforcement of law and enhancement of fair competition, government can and should help the consumer.”

Republican platform, 1984 (Ronald Reagan v. Walter Mondale):

- “American business and industry faced recession, unemployment, and upheaval, as high interest rates, inflation, government regulation, and foreign competition combined to smother all enterprise and strike at our basic industries.”

- “President Reagan’s immediate decontrol of oil prices precipitated a decline in real oil prices and increased competition in all energy markets. Oil price decontrol crippled the OPEC cartel.”

- “Government must not impose cumbersome health planning that causes major delays, increases construction costs, and stifles competition.”

During these years, Democratic platforms mentioned competition considerably more than Republican platforms. Indeed, the 1972 platform mentioned competition along with antitrust policies, but also turned its attention to foreign competition:

Democratic platform, 1972 (Richard Nixon v. George McGovern):

- “Step up anti-trust action to help competition, with particular regard to laws and enforcement curbing conglomerate mergers which swallow up efficient small business and feed the power of corporate giants.”

- [on family farms:] “And they need to be free of unfair competition from monopoly and other restrictive corporate practices.”

- [on international economic policy:] “Seek higher labor standards in the advanced nations where productivity far outstrips wage rates, thus providing unfair competition to American workers and seek to limit harmful flows of American capital which exploit both foreign and American workers.”

The 1976 platform mentioned oil prices and foreign competition, but also started expressing the idea that regulation may have a negative influence on competition:

Democratic platform, 1976 (Jimmy Carter v. Gerald Ford):

- “Competition in the private sector, a re-examination, reform and consolidation of the existing regulatory structure, and promotion of a freer but fair system of international trade will aid in achieving that goal.”

- “The Democratic Party believes that competition is preferable to regulation and that government has a responsibility to seek the removal of unreasonable restraints and barriers to competition, to restore and, where necessary, to stimulate the operation of market forces.”

- “When competition inadequate to insure free markets and maximum benefit to American consumers exists, we support effective restrictions on the right of major companies to own all phases of the oil industry.”

- “These measures must be accompanied by improved programs to ease dislocations and to relieve the hardship of American workers affected by foreign competition.”

The 1980 platform still linked competition with oil prices and foreign trade, but by that time it was also fully in support of deregulation in order to increase competition:

Democratic platform, 1980 (Ronald Reagan v. Jimmy Carter):

- “Consistent with our basic health, safety, and environmental goals, we must continue to deregulate over-regulated industries and to remove other unnecessary regulatory burdens on state and local governments and on the private sector, particularly those which inhibit competition.”

- “Encouraging investment, innovation, efficiency and downward pressure on prices also requires new measures to increase competition in our economy. In regulated sectors of our economy, government serves too often to entrench high price levels and stifle competition.”

- “We pledge vigorous antitrust enforcement in those areas of the economy which are not regulated by government and in those which are, we pledge an agency-by-agency review to prevent regulation from frustrating competition.”

- “Legislation must be enacted to prohibit purchases by oil companies of energy or non-energy companies unless the purchase would enhance competition.”

- “We will not allow our workers and industries to be displaced by unfair import competition.”

The number of mentions of competition in the 1984 elections was the highest ever for any platform, Democratic or Republican, at 26. In it, the Democrats continued focusing mainly on foreign trade but also on deregulation:

Democratic platform, 1984 (Ronald Reagan v. Walter Mondale):

- “The combined pressures of new products, new process technology, and foreign competition are changing the face of American industry.”

- “For the increasingly large part of American business that either sells overseas or competes with imports at home, the over-valued dollar abroad meant their products cost far more compared to the foreign competition.”

“Our very future in international economic competition depends on skilled workers and on first-rate scientists, engineers, and managers.”

- “We must encourage competition while preventing regulatory decisions which substantially increase basic telephone rates and which threaten to throw large numbers of low-income, elderly, or rural people off the telecommunications networks.”

- “We will not allow our workers and our industries to be displaced by either unfair import competition, or irrational fiscal and monetary policies.”

Since that 1984 peak, Democratic platforms seldom mentioned competition.

The Republican peak came in 1988 with 17 mentions. In the 1988 platform, the wording is much more confident as far as foreign trade is concerned, and deregulation as a tool to strengthen competition is expressly promoted, including, for the first time, in healthcare:

Republican platform, 1988 (George Bush v. Michael Dukakis):

- “Because Republicans have faith in individuals, we welcome the challenge of world competition with confidence in our country’s ability to out-produce, out-manage, out-think, and out-sell anyone.”

- “We will meet the challenges of international competition by know-how and cooperation, enterprise and daring, and trust in a well-trained work force to achieve more than government can even attempt.”

- “We hacked away at artificial rules that stifled innovation, thwarted competition, and drove up consumer prices.”

- “We will oppose regulation which stifles competition and hinders breakthroughs that can transform life for the better in areas like biotechnology.”

- [On health] “We fostered competition and consumer choice as the only way to hold down the medical price spiral generated by government’s open-ended spending on health programs.”

- “We will continue to promote alternative forms of group health care that foster competition and lower costs.”

Since 1988, mentions of competition in Republican platforms subsided, but not to Democratic levels. In 2016, Republicans still utilized the term more (9 vs. 4). Excerpts:

Republican platform, 2016 (Donald Trump v. Hillary Clinton):

- “We intend to facilitate access to spectrum by paving the way for high-speed, next-generation broadband deployment and competition on the internet and for internet services. We want government to encourage the sharing economy and on-demand platforms to compete in an open market, and we believe public policies should encourage the innovation and competition that are essential for an Internet of Things to thrive.”

- “The internet’s free market needs to be free and open to all ideas and competition without the government or service providers picking winners and losers.”

- “To ensure vigorous competition in healthcare, and because cost-awareness is the best guard against over-utilization, we will promote price transparency so consumers can know the cost of treatments before they agree to them.”

Democratic platform, 2016 (Donald Trump v. Hillary Clinton):

- “Promoting Competition by Stopping Corporate Concentration: Large corporations have concentrated their control over markets to a greater degree than Americans have seen in decades—further evidence that the deck is stacked for those at the top. Democrats will take steps to stop corporate concentration in any industry where it is unfairly limiting competition. We will make competition policy and antitrust stronger and more responsive to our economy today, enhance the antitrust enforcement arms of the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and encourage other agencies to police anti-competitive practices in their areas of jurisdiction.”