Warner Bros. (“Warner”), a prized and consequential media company, is once again on the auction block, and both Netflix and Paramount Skydance are competing to buy it. Barak Orbach observes that bidders’ appetites for prized media enterprises often foster undue optimism about the feasibility of successfully integrating them. He argues that antitrust scrutiny of any acquisition of Warner would likely underscore the need to modernize certain antitrust doctrines and analytical frameworks.

Since Warner Bros. (“Warner”) was founded in 1923, successive generations of corporate titans—from conglomerate builders to media moguls—have sought to fold the studio into larger corporate empires, and most of those transactions have later been unwound. Warner’s value—its brand, vast content library, and franchise portfolio—has long been undeniable. The enduring challenge has been making integration work. The latest contest over Warner’s fate, pitting Netflix against Paramount Skydance (“Paramount”), is therefore more than another Hollywood saga. It crystallizes a recurring clash between aggressive growth ambitions and coherent business strategy, and raises familiar concerns about how megadeals may affect competition.

Traditional content industries are characterized by high fixed costs, low marginal costs, strong network effects, and the need for reliable distribution networks or platforms, which push firms toward scale and integration. Yet new technologies and uneven business performance repeatedly force spin-offs, divestitures, and breakups, as seen in Warner’s two dissolved acquisitions by AOL and AT&T, and in its most recent merger with Discovery. Robust distribution systems and durable vertical arrangements can deliver real efficiencies and consumer benefits, but they can also concentrate control and entrench incumbents. In this environment, diverse incentives drive “megadeals”: firms may be adapting to change, integrating complementary assets (e.g., a streaming platform and content), pursuing market power, or indulging managerial appetites for growth. Some are also propelled by overconfident strategic visions that later collide with operational realities.

These factors would likely make the antitrust review of any acquisition of Warner a stress test for antitrust law. Analytical tools that perform well in traditional markets may be ill-suited to platform and ecosystem contexts, where competitive harm can arise through cross-market leveraging, data-driven advantages, and nonprice dimensions of rivalry such as quality, innovation, and product design. Accordingly, close scrutiny of a Netflix acquisition—or any alternative transaction involving Warner—would likely amplify calls to adapt certain antitrust doctrines and evidentiary frameworks to better reflect contemporary market realities.

Warner, Netflix, Paramount, and the current bidding war

Warner Bros. Discovery (“WBD”) is a media conglomerate formed in 2022 by combining Discovery and WarnerMedia. It owns Warner’s film and television production, a deep content library and franchises, the HBO Max streaming platform, Discovery+, and an extensive portfolio of domestic and international networks, including CNN and TNT Sports.

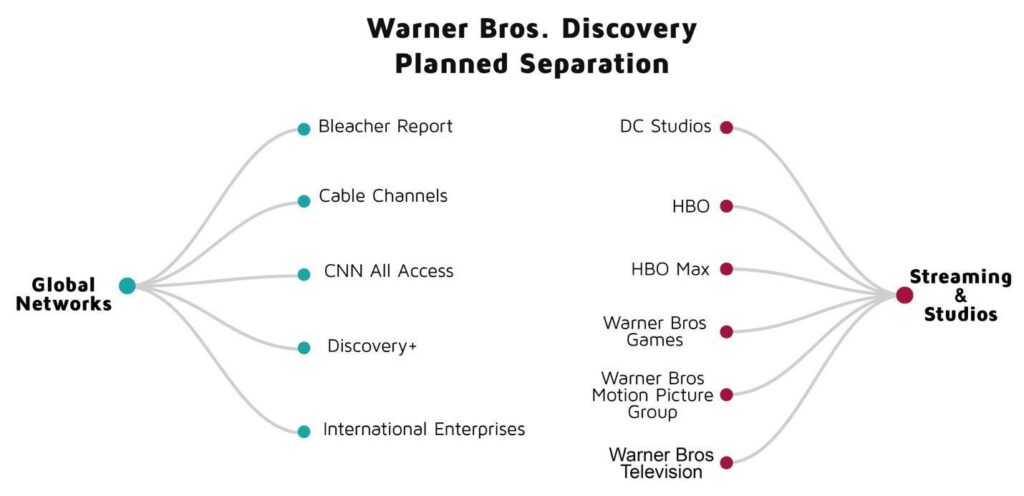

In June 2025, WBD announced a plan to separate into two publicly traded companies: one housing the studios (content production and distribution) and direct-to-consumer streaming operations, and another housing the Global Networks division and related digital products. WBD framed the separation as a value-unlocking move that would give each business a sharper strategic focus and a capital structure aligned with its cash-flow profile, especially by placing most of the company’s debt with Global Networks. In practical terms, the plan walked back the central 2022 integration thesis—that combining large-scale linear networks with studios and streaming would produce durable synergies. WBD acknowledged that the declining economics of legacy cable can weigh on the valuation and execution of the firm’s growth-oriented production and streaming businesses.

Netflix is the world’s leading subscription video‑on‑demand (SVOD) streaming platform and a disruptive force in filmed entertainment. Through product and distribution innovations—and a data‑intensive approach to personalization and programming—Netflix has repeatedly pressured incumbent studios, networks, and content distributors.

In early December 2025, Netflix and WBD Inc. entered into a definitive cash-and-stock merger agreement. Under the agreement, Netflix would acquire WBD’s Streaming & Studios business for approximately $82.7 billion. Closing is conditioned on WBD’s consummation of the separation of its Global Networks business, along with required regulatory and stockholder approvals and other customary closing conditions. The agreement also provides for a $2.8 billion break-up fee if WBD terminates the deal and a $5.8 billion reverse break-up fee if the acquisition is blocked on antitrust grounds.

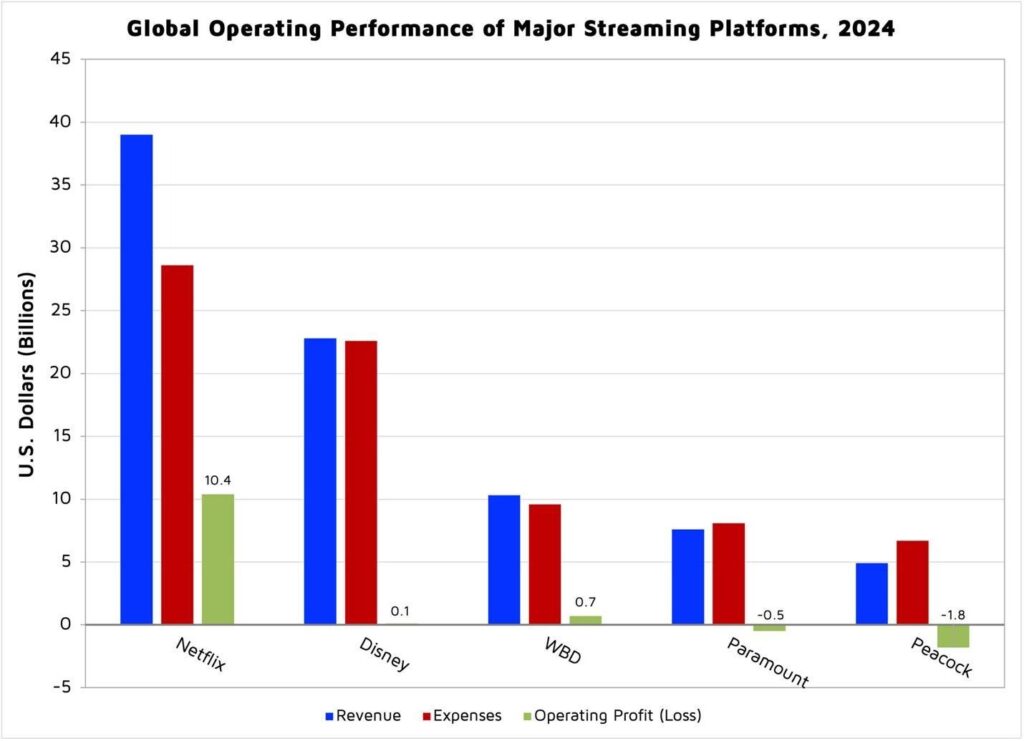

Should the deal be completed, it would combine two leading SVOD platforms that compete, among other dimensions, in the premium-content segment.

Paramount Skydance was formed through Skydance’s 2025 acquisition of Paramount. It is led by a newly installed management team that is still integrating Skydance and Paramount and lacks an established track record of operating and integrating an enterprise on WBD’s scale. Paramount’s library and operating assets are substantial but smaller than those of WBD’s. Specifically, Paramount’s streaming platform is materially smaller than Netflix and HBO Max.

In response to the Netflix/WBD deal announcement, Paramount launched an unsolicited all-cash tender offer for WBD, valuing the company at $108.4 billion. Although styled as a hostile bid, closing is conditioned on terminating the Netflix acquisition agreement and entering into a board-approved merger agreement. In its regulatory filings, Paramount stated that its bid would be backed in part by foreign sovereign wealth funds from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Abu Dhabi. That funding structure could trigger foreign-investment and licensing scrutiny—including potential CFIUS review and FCC foreign-ownership review.

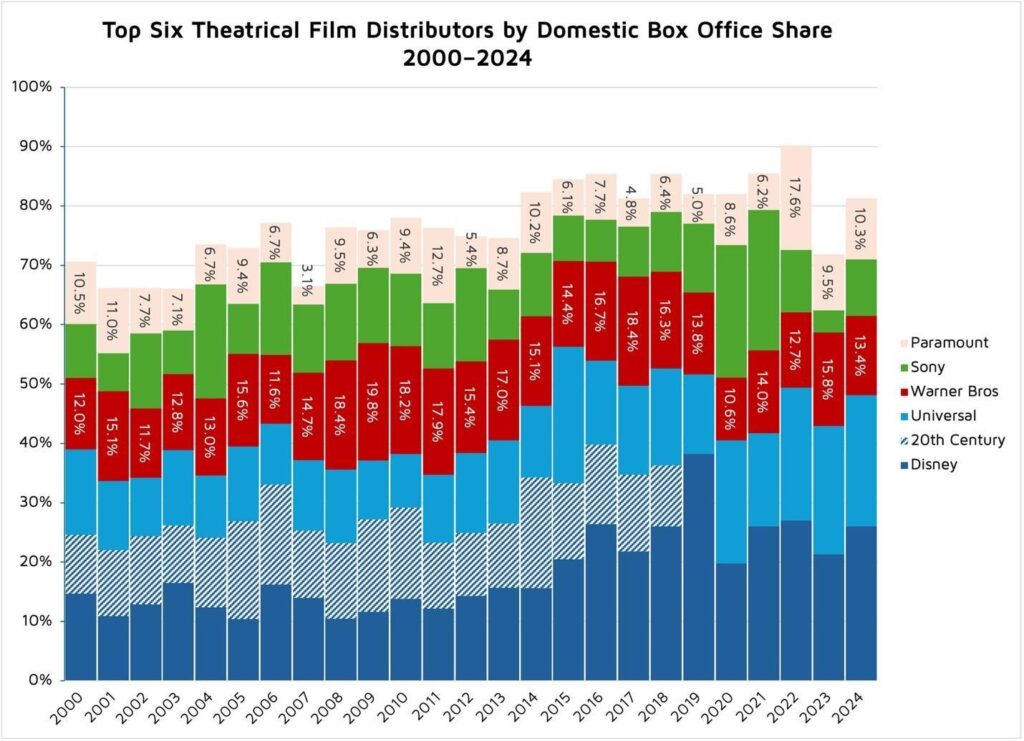

In an already oligopolistic theatrical distribution market, a Paramount/Warner merger would remove a significant independent rival for wide releases, increasing concentration and bargaining leverage in negotiations over screens, windows, and revenue splits.

Analytical challenges

Warner’s library, intellectual property rights, franchises, and operating assets—including production capabilities—make it one of the most consequential suppliers in content markets. As a meaningful competitive force, Warner’s investments and dealmaking decisions help determine which projects are financed, the bargaining environment for talent and rights, windowing and licensing strategies, and the extent to which platforms translate data, promotion, and portfolio depth into scale advantages. The antitrust task is to translate those channels into likely competitive effects in defined markets and along specific competitive dimensions, rather than treating every business or cultural consequence as legally cognizable harm.

Standard merger analysis is comparative: it asks how competition is likely to evolve with the transaction compared to the most plausible world without it (the “but-for” baseline). In most cases, that baseline is continued independent ownership—“deal versus no deal.” Here, “no deal” is not a realistic baseline. WBD has already set in motion a planned separation and a contest for control, making some acquisition the most likely trajectory. When the plausible but-for world may itself involve another transaction, competitive-effects predictions become unusually sensitive to baseline assumptions—and therefore harder to make decisive. But this analytical challenge is only one of several.

1. Market definition and the limits of “market-by-market” analysis

Under settled antitrust doctrine, courts evaluate competitive effects on a market-by-market basis. The analysis begins by defining the relevant product and geographic markets—that is, identifying who competes with whom and where. It then assesses market structure, including market shares, concentration, and the competitive significance of the firms involved. With that foundation, the central question is whether the challenged conduct (or proposed transaction) is likely to harm competition in the relevant markets.

This framework works best when the competitive effects are concentrated within a single market. However, when a single transaction affects multiple, interrelated markets, a market-by-market analysis may miss important mechanisms of harm. The approach becomes especially strained in ecosystem-style conglomerate media mergers—transactions that combine content creation, distribution, and (often) multiple advertising businesses. In those settings, the number of plausible candidate markets proliferates: ad-supported and ad-free streaming; premium pay television; theatrical distribution; scripted-television licensing; children’s animation; and multiple advertising markets. Each candidate can fracture further by release window, genre, language, and production budget, so “the market” can look materially different depending on how the slice is drawn. Even within a given slice, substitutability is contestable: high-budget productions are not necessarily interchangeable with low-cost titles, and streaming platforms differentiate through tiered offerings, pricing, advertising loads, and catalog depth.

Market definition is also particularly complicated in content industries because the “product” is malleable. Production companies can shift projects between film and television formats and distributors can adjust release sequencing and windowing strategies. The risk, in turn, is that any single market definition will obscure meaningful differences in substitution patterns across the consumer, production, and advertising sides of the business.

In addition, some of the most plausible competitive mechanisms relevant to media conglomerates operate across markets. A combined firm may use portfolio breadth to increase bargaining leverage; bundle content, distribution, or advertising inventory; and exploit scale advantages in data, promotion, and default placement to steer audiences and advertisers. These “portfolio effects” can tilt rivalry in adjacent markets, and no single relevant-market frame captures all material competitive effects.

The practical upshot is triage. Under established doctrine, enforcers must translate a sprawling set of products and interconnections into a manageable set of markets and theories that a court can readily understand—and that can support clear, enforceable relief. However, this methodology does not always capture significant competitive effects. A more credible approach would pair formal market definitions with an integrated assessment of cross-market leverage—how portfolio breadth, bundling, and scale advantages in data and promotion can reshape bargaining terms and tilt adjacent markets in the combined firm’s favor.

2. Thin buyer set

Only a limited set of firms—or a heavily financed consortium—could credibly acquire Warner (or WBD, depending on deal structure). A buyer would need not just capital, but the managerial capacity to integrate overlapping production, distribution, marketing, and technology functions. Paramount has emphasized this thin buyer set point in its public communications, portraying itself as WBD’s only viable suitor, implying that other potential acquirers would face prohibitive obstacles (including regulatory headwinds) given their existing market positions.

The thin-buyer-set constraint matters for antitrust in at least three ways. First, competition for the asset is not a substitute for competition in the affected markets. When the plausible bidders are themselves major incumbents, an “auction” does not preserve rivalry; it reallocates a key content library, production engine, and distribution capability among already-powerful firms.

Second, thin buyer sets make remedies harder to design and less reliable. Structural relief typically depends on divesting a business (or package of assets) to a buyer that is (i) independent, (ii) willing, and (iii) able to operate the divested assets as a durable competitive force—without ongoing regulatory supervision. Where the pool of potential buyers is narrow, the most obvious buyers may be the same incumbents that raise competitive concerns. The problem is especially acute in media, where the economically relevant “asset” is often a set of complements—rights, relationships, promotion capabilities, and distribution—that can lose value when carved up. Divesting isolated franchises or portions of a content library might seem manageable on paper, but can miss the competitive edge gained by concentrating these assets in one library.

Third, in interconnected media markets, ownership changes can propagate beyond any single product market. Control over premium content and distribution can shift bargaining leverage across licensing, advertising, exhibition, and talent contracting, and can facilitate cross-market strategies—such as bundling and other cost-raising tactics—that disadvantage rivals while avoiding clean detection within a single market-definition frame.

3. Uncertainty and risks

Predicting competitive effects in dynamic content markets is particularly difficult because the “but-for” counterfactual—the world absent the merger—is itself a moving target. Product design, pricing models, distribution channels, and business strategies evolve rapidly. As a result, harm to competition may occur through both price effects (e.g., higher prices or less favorable contract terms for trading partners) and non-price effects (e.g., lower pay for suppliers and workers, or fewer and lower-quality options for consumers). These dynamics make any forward-looking assessment highly sensitive to modeling choices and to assumptions about how the market would have evolved absent the merger.

To illustrate the challenge, consider price effects—the workhorse of merger analysis—for streaming services. For much of the past decade, streaming platforms priced aggressively to build scale. As that phase has waned, streamers have increasingly monetized by redesigning access—tightening rules around password sharing and proliferating tiers that range from lower-priced, ad-supported plans to higher-priced ad-free or “premium” packages. Traditional price analysis, therefore, risks anchoring on a baseline that is already being rewritten by sector-wide repricing and business-model restructuring, rather than a stable “today plus a small increment.”

In addition to challenges related to forecasting future effects, complex megamergers pose execution risks. Integration risk is not just an internal management issue; it can affect competition. A deal that combines a data-driven streaming platform with a legacy studio must knit together very different systems: greenlight decisions (what gets made), talent contracts, operating processes, and release strategy across theaters, streaming, and television. If the integration bogs down, the merged firm may spend years reorganizing, which can translate into fewer or slower releases and weaker competitive pressure in the meantime.

These risks are especially relevant here. Netflix has become a major producer, but it has no experience running the kind of large-scale, multi-year franchise production, and the day-to-day theatrical distribution and movie-theater relationships. Paramount, meanwhile, is still adjusting to the complex merger that created the company. Adding WBD would test management bandwidth, and it is not clear why this additional combination would fix WBD’s problems rather than simply combine multiple sets of difficulties. Because merger review has limited tools to incorporate execution risk directly, enforcers should treat promised efficiencies with caution and credit them only when supported by concrete integration plans, milestones, and accountability.

4. Domestic effects of global operations

Content markets operate on a global scale, but antitrust merger review focuses on effects in domestic markets. Netflix, WBD, and Paramount do business in dozens of countries, and many of their key choices—what to produce, when to release it (“windowing”), and how to license it—are made with a global audience in mind, not just one country. Even so, antitrust analysis must determine how a proposed merger would affect competition at home, including when the sources of advantage are global: larger pools of viewer data, stronger platform technology and promotion, and the ability to spread content costs across subscribers worldwide.

At the same time, transactions involving global firms are frequently reviewed by multiple jurisdictions. Parallel investigations can produce divergent theories of harm and remedies. In practice, the most restrictive jurisdiction often becomes the binding constraint, effectively shaping the merged firm’s global operating model—including its conduct in the United States.

Conclusion

Some commentators have treated Warner’s recent history of mega-deals—AOL/Time Warner (2001), AT&T/Time Warner (2018), and Discovery/WarnerMedia (2022)—as evidence that massive scale and scope cannot be managed effectively and inevitably harm competition. Such a narrative, however, often discounts consumer demand for low-cost access to deep content libraries. The question is how enforcement agencies should evaluate mergers and acquisitions that create or reshape media conglomerates. This article argues that any serious effort to assess the competitive effects of Netflix’s proposed acquisition of Warner (or a plausible alternative transaction) will likely expose the limits of existing analytical frameworks for evaluating complex integration in contemporary media markets. In this sense, the review of the proposed deal would reinforce the widely recognized view that parts of antitrust law require updating—and, in some areas, reform.

Author Disclosure: Since 2021, the author has served as a legal advisor to the Independent Cinema Alliance. He previously advised a range of entities, including government agencies, companies, and investors, on antitrust and business strategy matters in the filmed entertainment industry, including distribution and pricing. The author reports no other conflicts of interest, and the views expressed are his own.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.