Why has antitrust enforcement declined in the United States since the 1970s? Is it due to the preferences of voters or business influence? In this symposium, Jonathan Baker, Eleanor Fox, and Herbert Hovenkamp will discuss the findings of Eric Posner, Luigi Zingales and Filippo Lancieri’s new paper, “The Political Economy of the Decline of Antitrust Enforcement in the United States.” Lancieri summarizes the findings of the paper here.

Scholars, policymakers, and commentators have been talking about regulatory capture for more than 50 years. George Stigler’s seminal work spurred a growing literature in political economy focused on understanding the mechanisms—from revolving doors to lobbying, campaign donations, and training programs—that companies employ to shape governmental activity. Yet, while fascinating and increasingly sophisticated (we need much more of this!), this literature struggles to capture big-picture processes or the ways through which special interests might combine these tools to influence public policy. This long-term capture process—that some have coined cultural capture, or epistemological capture—is the hardest to detect, not only because it is slow and multi-faceted, but also because it does not require malfeasance by those involved. Rather, changes in long-term incentives and the informational environment push policymakers to believe that they are defending the public interests, while ultimately promoting the agenda of a given interest group.

In an article recently published in the Antitrust Law Journal, Eric Posner, Luigi Zingales, and I study how special interest influence might explain the pro-defendant (pro-business) shifts in United States antitrust laws since the mid-1970s. We outline a three-step methodology that can help scholars identify such long-term capture processes and then apply it to the changes made to U.S. antitrust policy over the past decades. Our results suggest that these received only the lowest levels of democratic sanction, and most likely reflected the interests of big business, not that of consumers or society more broadly. Importantly, we study aggregate effects that materialized as a result of decisions that took place over decades. We have no evidence nor do we imply that that anyone engaged in malfeasance.

Step I: Mapping the level of democratic sanction to the changes in policy

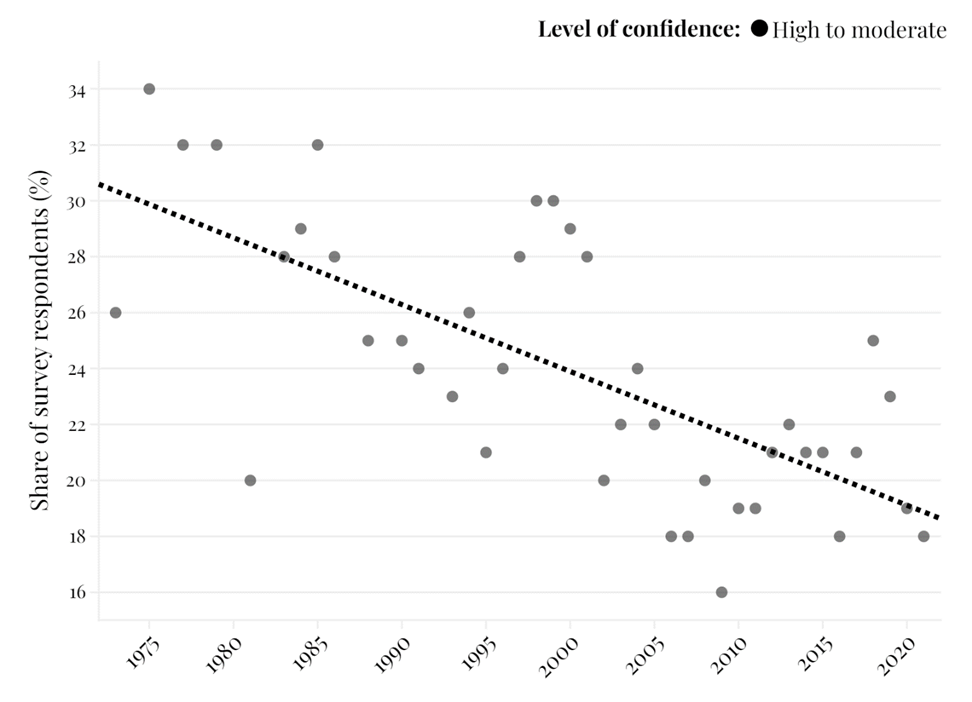

The first step is to understand whether the significant decline in antitrust enforcement since the mid-1970s/early 1980s was the result of voters wanting less antitrust. To identify this “democratic sanction,” we first surveyed historical polling data on antitrust and market power broadly defined as a proxy for direct political preferences. No representative polls indicate that the public turned against antitrust enforcement over the last half-century. For example, since 1973, Gallup has asked a representative sample of U.S. voters what their public confidence in big business is. Such levels of confidence has tanked over the past 45 years.

FIGURE 1: PUBLIC CONFIDENCE IN BIG BUSINESS (1973–2021)

Second, we looked at presidential campaigns. The assumption here is that elected officials are trying to reflect the preferences of a majority of the electorate in their proposals and major speeches. Surprisingly, discussions on antitrust and monopoly have been present in the majority of races since 1932—though they underwent a significant hiatus between 1990 and 2016. No U.S. president won an election while affirming that their campaign platform was to decrease antitrust enforcement—on the contrary, antitrust enforcement has historically received strong bipartisan support. Even Ronald Reagan’s 1980s party platform, for example, stated that the deregulation of the transportation sector should lead to increased antitrust enforcement to ensure that “neither predatory competitive pricing nor price gouging of captive customers will occur.”

Third, we look at the laws passed by Congress. As Daniel Crane has aptly documented, antitrust is a policy marked by significant anti-textualism—the courts have historically limited the reach of antitrust statutes that have a clear general goal of increasing enforcement.

In other words, U.S. antitrust law and policy changed in the shadows of direct public opinion—mostly through the actions of unelected judges and government officials. The next question, then, is to understand whether the Senate confirmed judges and officials who openly expressed, during their confirmation hearings, their skepticism of antitrust enforcement.

No clear mandate exists. After studying all nomination hearings for leadership of the antitrust agencies—the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice Antitrust Division—since the 1950s, the clearest pattern that appears is one of the nominees either expressing strong support for the enforcement of the antitrust laws or simply providing evasive, non-committal answers to direct questions about their enforcement views. A good example is the exchange between Senator Wendell Ford and Daniel Oliver, President Reagan’s nominee for the position of Chairman of the FTC in 1986—at the height of the anti-antitrust, de-regulation movement:

Senator [Wendell] FORD. Do you believe that small businesses are entitled to the protection of the antitrust laws and the Federal Trade Commission Act by enforcing the law against unfair competition and predatory acts by larger, more powerful competitors?

Mr. [Daniel] OLIVER. Well, Senator, I think that those laws should be enforced. Just exactly what the effect is in any particular case is hard to say. I think that the laws should be enforced. I think it is probably hard to say always how the chips fall when the law is enforced as it is written.

. . .

Senator FORD. Let me ask you this: Do you support amending the antitrust laws so that treble damages are eliminated except for horizontal price fixing cases?

Mr. OLIVER. Senator, I understand the administration has a proposal like that, if it is not exactly like that. I was not consulted, clearly, obviously, as the administration constructed that proposal. I have not read any background papers, reports or studies or statistics in connection with it. And I, therefore, really have no informed opinion of whether that is necessary or not. I am perfectly happy to look at it and it may well be a good idea, but it is not a matter that I have studied myself and I hesitate to give an answer without having an informed opinion.

Senator Ford. You are going to be chairman. While I understand that you haven’t been there yet, and you haven’t had an opportunity to study these questions, once you become Chairman, that is the end of it. And we don’t know what your attitude is prior to going in. That is one of the reasons for the hearings. And we seem to always get evasive answers.

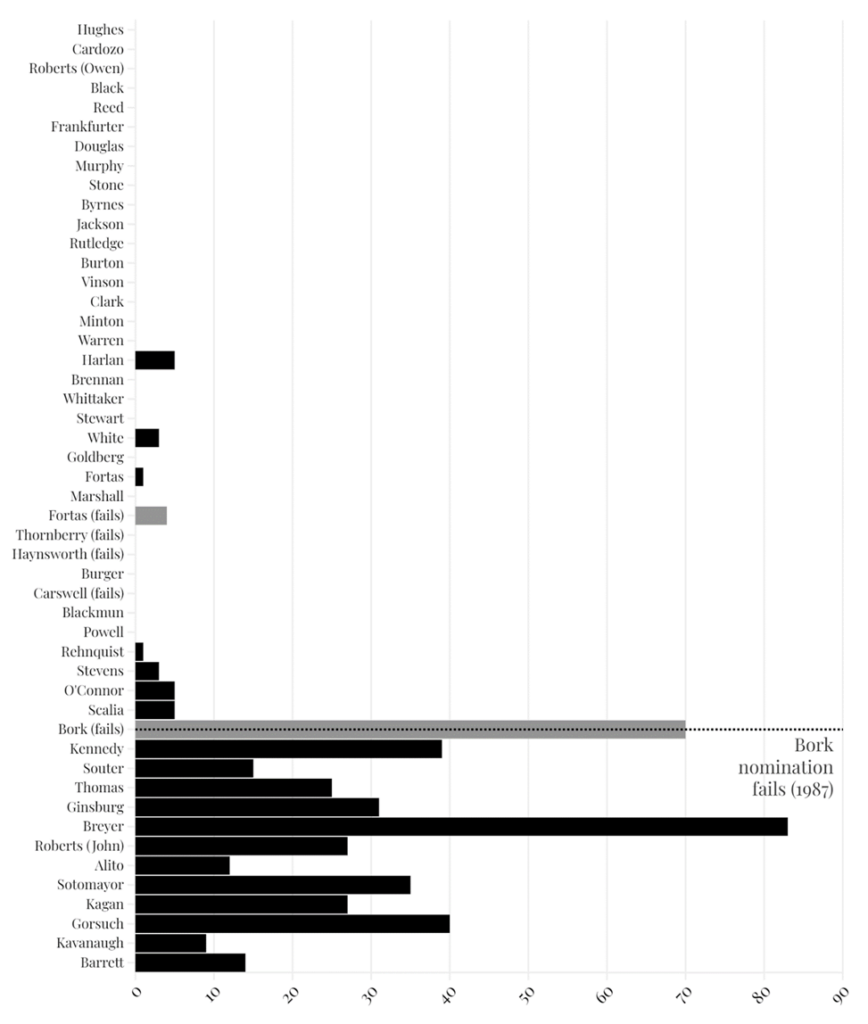

Indeed, between the 1970s and 2016, the median duration of nomination hearings for such high-profile positions decreased from 90 minutes (Nixon’s appointments) to 20 minutes (Obama’s appointments), suggesting little opportunity for the agency heads to articulate their views on antitrust, let alone defend one of weaker enforcement. A somewhat similar pattern exists for the nomination hearings of Supreme Court justices. Antitrust was largely a non-topic in nomination hearings until the appointment of Robert Bork in 1987.

FIGURE 2: TOTAL REFERENCES TO ANTITRUST AND MONOPOLY IN SUPREME COURT NOMINATION HEARINGS, PER NOMINEE (1930–2020)

Bork received significant bipartisan pushback on his anti-enforcement antitrust views, considered extreme. After him, nominees either expressed their lack of knowledge/interest in antitrust policy or affirmed that they would ensure the strong enforcement of the laws. The nomination of Justice David Souter provides a good example. When asked to reaffirm the importance of the Sherman Act in protecting against market consolidation, he responded:

Justice Souter. I also have been well educated by Senator Rudman over the years in the value of small business. Small business has no better friend than he has, and I think one of the lessons that I have absorbed from a long period of my professional lifetime with him, if I needed to absorb that from anyone else, is the importance of a degree of competition which will allow small business to emerge and allow for diversity in the American economy, which it is the object of the antitrust laws to secure, as much as that is possible.

Senator Kohl. Do you agree, Judge Souter, that an important purpose of the Sherman Act is to protect against consolidation of economic power and make sure that consumers are not abused by companies engaged in monopolistic business practices?

Justice Souter. There is simply no question about it, either as a historical matter or as a strictly legal matter, as one examines the precedents. The ultimate object of the system, it seems to me, has to be judged on its systemwide effects. I do not think the antitrust laws should even be seen as merely consumer laws or as anti-business laws, but as laws intended to assure a free and open and competitive economic system for everyone.

Justice Souter would do otherwise once he reached the bench. He ruled on 23 antitrust cases. Nineteen of those were cases involving private antitrust enforcement, where a usually relatively smaller company is suing a larger company. In 18 of those 19 cases, Souter voted in favor of the defendants (the larger company). Out of his 23 total antitrust rulings, Souter voted in favor of the defendants in 20 of them.

Step 2: Did the technocracy deliver?

Both direct and indirect sources of democratic legitimacy indicate that American antitrust enforcement declined in the shadows of broader public accountability. This alone does not support a general finding that special interests captured antitrust policy. There are good reasons why we entrust certain complex policies to independent technocrats. At the same time, special interests thrive in the world of quiet politics. This means that, when such delegation takes place, technocrats have a higher duty of motivation—and, in particular, a duty to reverse course if the policy is not delivering on its stated goals.

The second step in the inquiry, then, is to understand whether the changes implemented over the last several decades helped U.S. antitrust policy accomplish its objectives. One can have a long discussion on what are the central goals of competition policy. Still, most would agree that, at minimum, antitrust should increase market competition and economic efficiency and control market power.

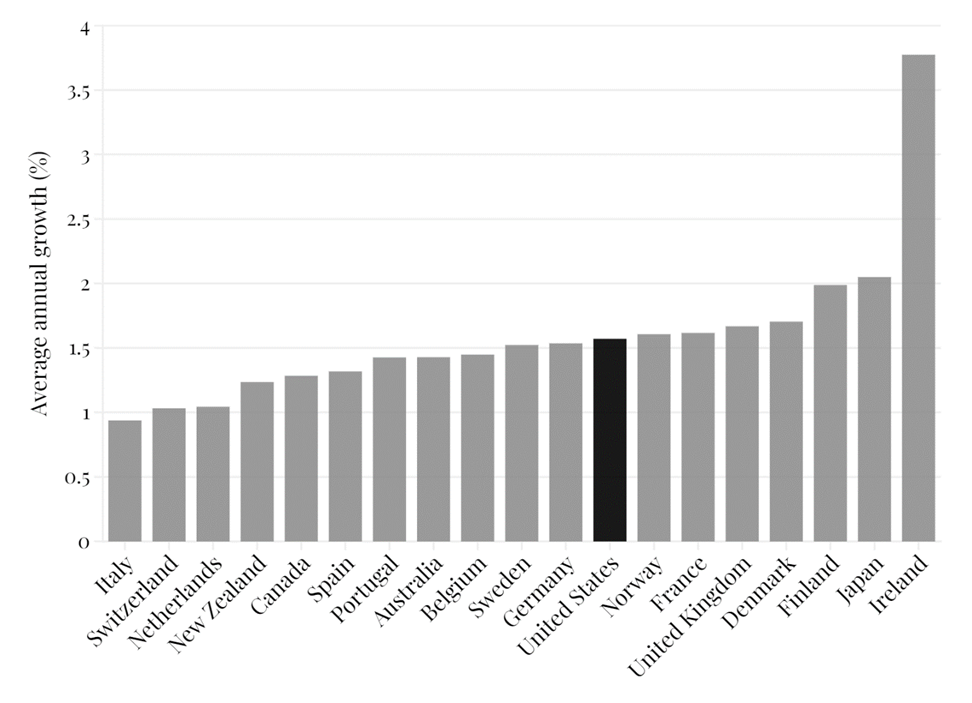

A large and growing body of literature in economics shows this was not the case—the changes to the implementation of U.S. antitrust laws primarily benefited large businesses at the expense of the rest of society. The literature is too large to cover here, but merger reviews regularly find that consummated mergers lead to higher prices and lower output. Productivity growth declined significantly in the U.S. over the past decades, and a comparison with “peer-economies” does not look much better.

FIGURE 3: AVERAGE ANNUAL GROWTH IN GDP PER HOUR WORKED, SELECTED COUNTRIES (1980–2020)

In the meanwhile, markups have gone up, while the labor share of profits has gone down, median salaries stagnated, and business dynamism declined (among others). Antitrust is certainly not the sole cause of these trends—changes in technology, tax and trade policies, and other factors also play an important role. But antitrust is one of the key policy levers through which the government manages the economy, so it is also to blame for these trends. And this, again, is under the narrowest definition of what antitrust should strive to accomplish as a policy. It ignores how antitrust failed workers in particular, the role of competition policy in helping constrain political power, the many failures of antitrust enforcement in vertical relations—the list goes on and on…

Step 3: Can we identify specific mechanisms special interests employed to shape policy to their advantage?

The final step in a diagnosis of capture is to identify specific mechanisms employed by special interests when trying to influence the policy.

This is the hardest step: companies do not tend to openly advertise their attempts to influence regulators lest they risk galvanizing public opposition. One can, though, try to identify changes in motives and opportunities.

The mid-1970s witnessed a relative decline in the competitiveness of American businesses vis-à-vis international competitors, which provided such businesses with a motive and an opportunity to lobby for decreased antitrust enforcement. Indeed, companies regularly cited back then (and still cite) foreign competition as an excuse to push for decreased antitrust enforcement.

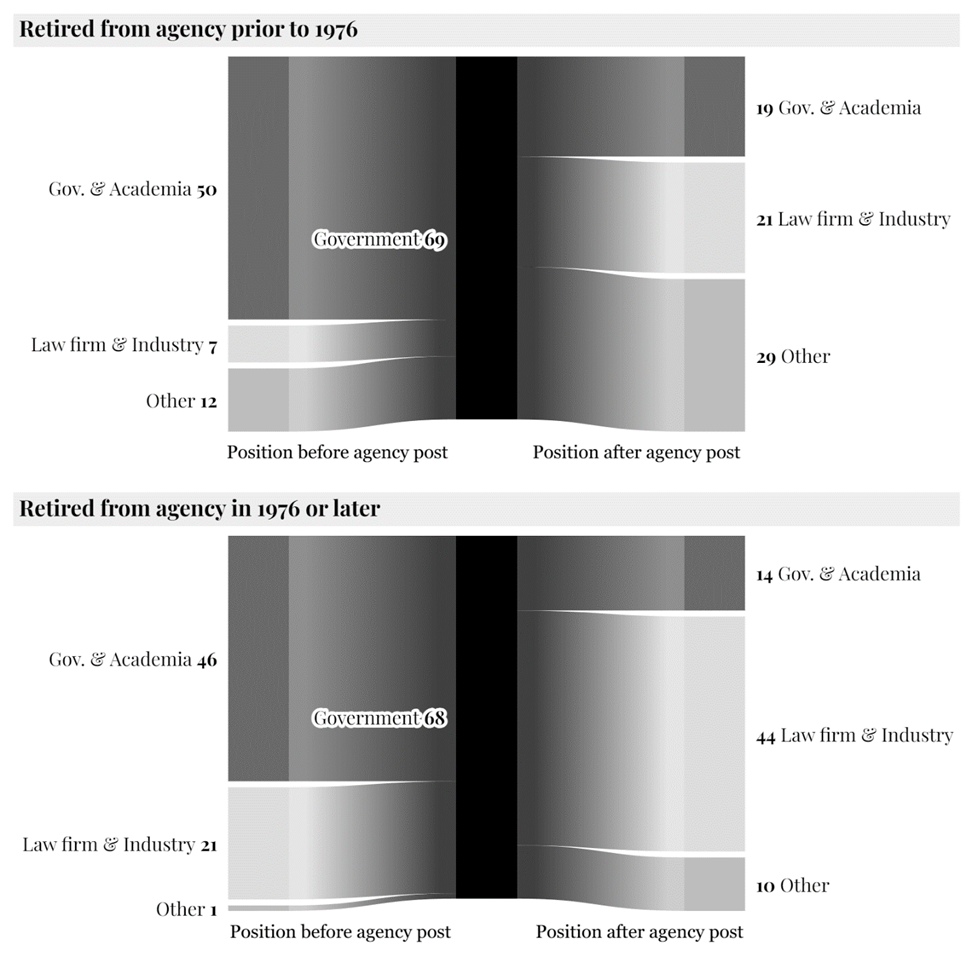

Corporations’ incentives to influence competition policy perhaps best-found expression in the famous 1971 Powell Memorandum, in which Lewis Powell Jr., a year before his ascent to the Supreme Court, advised the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on the need to galvanize the resources and expertise of American businesses to better protect their interests in the political arena. Subsequently, companies and their shareholders exploited the relaxation of campaign financing and other rules to increasingly influence Congress and the government more broadly. One way to measure this is by looking at the revolving door: the decline in antitrust enforcement is correlated with an explosion of top DOJ and FTC officials going to work for the defense bar immediately after retiring from their agency role.

FIGURE 4: COMPOSITION OF FTC COMMISSIONERS’ AND DOJ AAGs’ CAREER TRAJECTORIES, PER ENFORCEMENT PERIOD

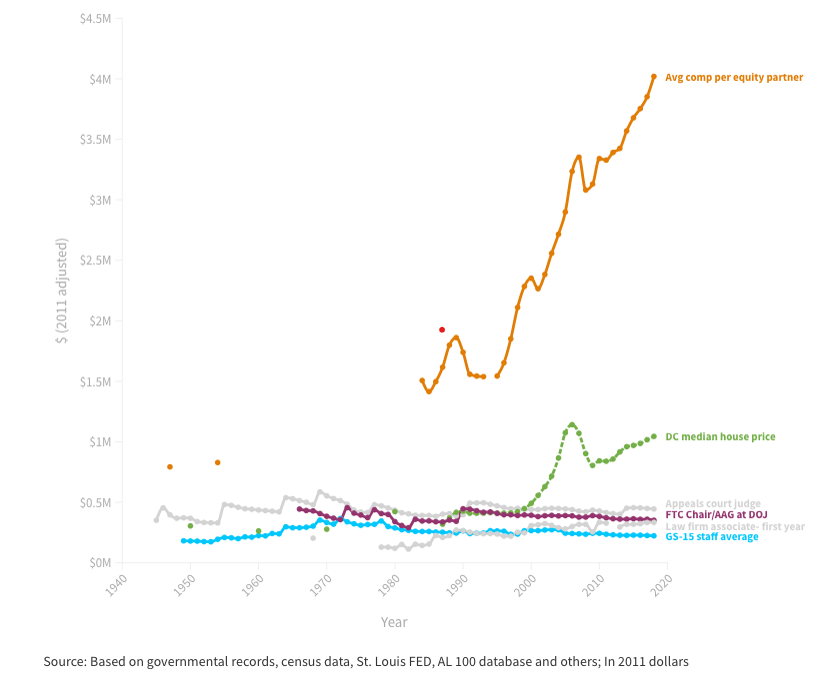

More rigorous studies have also increasingly identified the magnitude of corporate influence on antitrust enforcement. For example, companies that increased their general lobbying expenses before large mergers are more likely to receive a favorable response from antitrust authorities. The opposite is also true, as mergers lead firms to increase their lobbying expenditures by an average of more than 20%. Finally, multiple studies also show how the FTC also reflects the preferences of members of Congress. For example, the agencies analyze mergers differently if the engaged companies are headquartered in the district of powerful Congressional members with direct oversight power over the Agencies. Indeed, one way to understand why such channels are powerful is to look at incentives. We did so by looking at the salary differential between governmental officials and their alternatives in private practice. Over the past 40 years, this gap has grown tremendously.

FIGURE 5: COMPENSATION AND HOUSING PRICES FOR LAWYERS IN THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTORS (1945–2020)

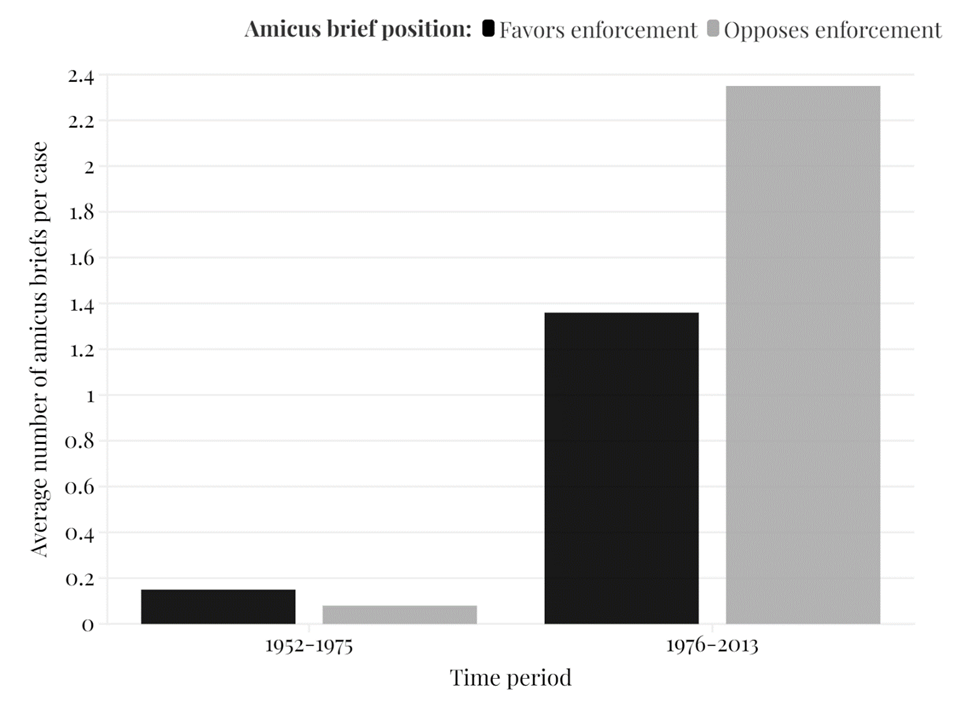

Large companies also paid increasing attention to the U.S. federal judiciary—either through direct involvement in litigation or by encouraging the appointment of business-friendly judges. Antitrust defendants sponsored law and economics courses for judges as a way to shift decisions in their direction. They also became increasingly engaged in litigation by selecting and promoting cases and filing Amici Curiae against antitrust enforcement.

FIGURE 6: RATIO OF AMICUS BRIEFS POSITIONS ON ANTITRUST CASES, PER PERIOD (1952–2013).

While looking at all this evidence, it is important to keep in mind that antitrust, as a policy, is trying to prevent the largest, more sophisticated companies in the U.S. economy from increasing their profits through illegal mergers or other behavior that allows them to further control markets. Finding that such policy is subject to significant influence by business interests should not be surprising. All in all, we believe that this and other evidence we discuss in the article is more than enough to shift the burden of proof—it is now up to defendants of the changes in policy to make the case that technocracy has prevailed and businesses just wasted money and resources: antitrust is somehow the only public policy in the United States that is protected from industry influence.

A final, interesting question that comes out of this study on this shift of antitrust policy toward weaker enforcement since 1970 is what is the role of the so-called “Chicago School.” Our view is that the Chicago School was influential, but in different ways than people realize. First, one has to acknowledge that much of its criticism of antitrust in the 1950s-1970s was justified and that a shift in policy was warranted. Ultimately, though, the ideas of the school helped business interests overcome collective action problems and galvanize around a common goal, while also helping clothe private interests under a public-spirited rationale. This is why big business and its allies funded Chicago-School ideas while also donating money to candidates and parties who advanced their interests. Academia has since moved away from the ideas of the Chicago-School, but many areas of policy are yet to catch up. That is because business co-opted and promoted Chicago School thinking to advance its interests: it is unlikely that the Chicago view would have spread so fast, and it would certainly not have dominated jurisprudence for so long, without the financial support of powerful economic interests.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.