ProMarket contributing editor Walter Frick interviews Bruno Pellegrino about his paper with Florian Ederer, “The Great Startup Sellout.”

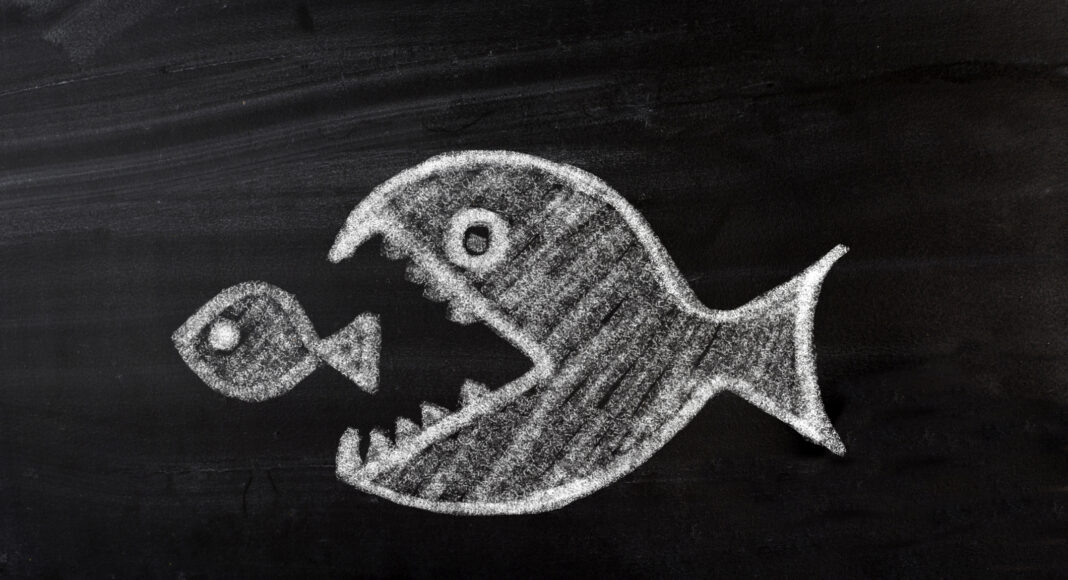

New companies are supposed to be a force for competition, potentially “disrupting” incumbents and pushing them to innovate. But something has changed about that process. Startups don’t seem as disruptive as they once did, and more of them are being acquired by other firms rather than going public.

In a recent paper on “The Great Startup Sellout,” Bruno Pellegrino of Columbia University and a Stigler Center affiliate fellow, and Florian Ederer of Boston University, study how the changing life cycle of startups is affecting competition in the US economy. They conclude that the companies acquiring startups have become more and more insulated from competition.

ProMarket asked Pellegrino to explain the research and what it means for competition policy.

How has the life cycle of a startup changed in the last 35 years?

It depends on what we include in our definition of “startup”. There is the more common type, which is exemplified by the convenience store down the corner. The other type is the one we care about, which includes the Amazons and the Modernas. This latter type is much rarer but much more important for competition policy: this is the type of startup that is typically funded by venture capital. With respect to the first type, the basic fact is that we have fewer. This is the so-called “decline of business dynamism.” We see less and less business creation across the US economy, and this has been going on since the 80’s.

Things are very different for the VC-backed startups. Over the same period, the number of VC-backed startups has exploded. That should be great for competition. However, the other thing that has changed is that, unlike during the 80’s and early 90’s, almost none of these startups survives in the long run as an independent entity.

The biggest change that we have observed among these startups is the mode of “VC exit” — that is, how VC investors monetize their investment. In this new paper with Florian Ederer, we show that while in the 80’s and early 90’s almost every successful VC-backed startup would eventually do an IPO (the IPO was the “final goal”), this has changed completely. Today almost every successful VC-backed startup eventually gets acquired. IPOs have become extremely rare: Uber is the exception, not the rule.

Your paper suggests this shift away from IPOs has helped incumbents avoid competition—how do you reach that conclusion?

Just to be clear: we are not saying that all acquisitions of startups are necessarily anticompetitive. However, a general problem with startup acquisitions is that they do not get any antitrust scrutiny: the reason is the value of the acquisition (when disclosed) is typically too small to meet the threshold for reporting to antitrust authorities (the HSR threshold).

Hence, acquisitions of startups provide an avenue for incumbents to restrict competition against which we have little remedy from an antitrust perspective.

Another challenge is that most of these acquisitions take place in emerging tech industries where antitrust markets are notoriously difficult to delineate. (To understand whether a firm is monopolizing the market you need to be able to argue who are the relevant competitors). This is what is known in the antitrust literature as the problem of “market definition.” To give you an example: when the DOJ or the FTC sues a firm for attempted monopolization, the firm will always have a strong incentive to define its market very broadly (i.e. they have plenty of competitors), while the agencies will obviously try and argue the opposite.

In my own earlier paper on Network Oligopoly I developed a novel conceptual framework that allows me to analyze the market power of firms by taking a “non-ideological” approach to the problem of market definition. In my framework, product markets are not collections of “sectors” or “industries.” Instead, I model product markets as a network. In this framework, we are able to measure the market power of tech giants using a metric of network centrality: a firm that is very “peripheral” in the network of product market rivalries is a firm that has market power. No one is “near” enough to compete.

Going back to the initial question of how we can investigate the role of startup acquisitions: one way we can do that is to look at the evolution of centrality for firms that acquire lots of startups. In this newer paper with Florian we use this centrality metric and focus on the usual suspects: Google, Apple, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft. What we observe is that the centrality of these firms has collapsed to incredibly low levels, suggesting they face less competition.

Another tell-tale sign that suggests that startup acquisitions are responsible for at least some of the increase in market power of incumbents is that, over time, startups that do go public are much more productive than what, in theory, would be required for them to enter and earn positive profits. This suggests that these startups face potentially a high opportunity cost of doing an IPO and competing with existing businesses, which is potentially related with the opportunity of being acquired by an incumbent.

Are there other possible explanations? Could these acquisitions increase market power via innovation that benefits consumers?

Absolutely. It is very likely that that is also happening at the same time. Therefore, when we evaluate startup acquisitions through the lens of competition policy, we need to trade-off their potential anticompetitive harm with potential benefits for the consumer that could arise, as you noted, from the integration of the startup with an existing business or platform.

The problem is precisely that, because until very recently most startup acquisitions did not receive any type of antitrust scrutiny, and because data on these startups is lacking, policy-makers and researchers are unable to say much about this tradeoff.

This is problematic in and of itself, because it introduces a terrible incentive for large incumbents that have lots of cash on hand and can acquire lots of startups: a dominant incumbent knows that it can preempt the emergence of new competitors by simply buying them out at the startup stage. Because the acquisition does not receive antitrust scrutiny, this effectively equates to a loop-hole in our antitrust regulatory framework.

Are startup founders and VC backers the beneficiaries here? Or are they being harmed, too?

The honest answer is we do not know. It depends on the nature of the trade-off they face when they have to choose whether to sell out to incumbents. It also depends on their bargaining power vis-a-vis potential acquirers.

For example, suppose that the alternative to being acquired is that the incumbent will hire all of my key staff at a wage above their marginal product of labor (rendering me unable to compete in the long term). Then I have no choice but to accept their buyout offer. The theory of harm in this example is basically a form of predatory pricing in the labor market. I could list other examples of other anti-competitive threats that a startup could be faced with.

If startup founders and backers have low bargaining power due to the threat of having to compete with an incumbent who may abuse their dominance position down the line, then this is clearly a problem for them, too. We need more research on this, for sure.

If startup acquisitions are lowering competition and hurting the economy, how should policymakers respond?

One reason why startup acquisitions do not receive scrutiny is that right now the agencies do not have the capability of reviewing all mergers. In order to remove the bad incentives, we need to empower the agencies to investigate this new type of acquisitions. We do that in two ways: 1) on the academic side, we need to develop theories of competitive harm that effectively represent the tradeoff startups and their acquirers are faced with. Luckily there is a lot of very interesting research (mostly theoretical) currently being developed. 2) We also need to provide the agencies with better resources, which is a political choice.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.