Social trust in democratic institutions affects the ability of those institutions to carry out policy. In new research, Rustam Jamilov shows how decreasing trust in the U.S. institutions has reduced the ability of the Federal Reserve to influence the economy in states that exhibit lower levels of trust.

Trust in institutions can shape the way individuals and firms react to changes in monetary policy. Lack of trust hampers the ability of the central bank to affect the economy, even in the short run. Institutional credibility and integrity—especially in a world of rising populism—are critical for monetary policy effectiveness. For example, distrustful agents may underreact to monetary policy announcements or question the monetary authority’s commitment to its mandate.

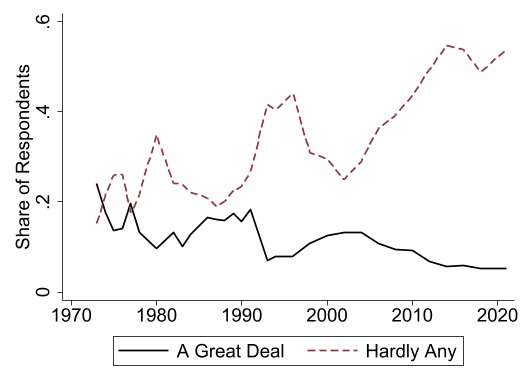

Trust in institutions has been declining in the United States for decades (Figure 1). This trend is extremely concerning because generalized trust is an essential component of a networked society. It encompasses civicness and transactional reciprocity, which in turn enable the society to function effectively. The influence of trust—or social capital—on fundamental economic forces, ranging from growth and development to financial market participation, has been well documented. In high-level policy circles, research on trust is becoming increasingly integral for informed government regulations.

Figure 1: A Crisis of Trust

Note: Responses to the survey question “Do you have confidence in congress?” Figure is from Section 1 of Jamilov (2023). Original data is from the General Social Survey.

The relationship between trust and central banking, however, remains poorly understood. What is the impact of trust on monetary policymaking? Has the collapse of trust diminished monetary policy effectiveness? In a new paper, I document that U.S. states with high levels of trust in institutions are systematically more responsive to changes in monetary policy. In conjunction with a simple behavioral New Keynesian model, I conjecture that the secular decline in trust may have contributed to a significant reduction in the ability of the Federal Reserve to influence the economy. My findings warn that crises of trust could lead to crises of policy inefficacy.

The Geography of Trust in the United States

My empirical approach builds on the burgeoning empirical literature that exploits spatial variation for identification. I begin by measuring regional variation in trust with geo-coded survey-based indicators from the 6th wave of the World Values Survey (WVS). Surveys have been shown to be a useful measurement tool for the study of information rigidities, the pass-through of policy interventions, and elicitation of first-order social concerns. For our purposes, we focus on 20 questions that try to elicit trust and confidence in institutions. These questions ask the respondents to evaluate their confidence in the government, parliament, banks, major companies, etc.

Figure 2: The Geography of Trust in Institutions

Note: This figure shows regional variation in the indicator of trust in institutions. Numbers have been scaled to lie in the [1,10] interval where 1 indicates low trust and 10 indicates high trust. The District of Columbia and Hawaii are not shown. Details on index construction are in Section 2 of Jamilov (2023). Original data is from the World Values Survey.

I then took the best-fit line of the weighted averages of individual survey responses at the state level to construct the baseline, low-dimension, state-level measure of institutional trust: TrustInstitutions. Figure 2 plots the regional distribution of TrustInstitutions. One can see rich heterogeneity in institutional trust, ranging from low-trust states like North Dakota, Idaho, and Alaska to high-trust states like Vermont, Connecticut, and Nebraska.

Regional Trust and U.S. Monetary Policy

The main empirical test consists of two simple steps. First, I run quarterly state-level regressions (local projections) of local real GDP growth on the monetary policy shock. Specifically, the shock represents a contraction that should lead to a decline in economic performance. In Step 2, I run a cross-sectional regression of the estimated coefficients on our main variable TrustInstitutions and additional controls. A negative and statistically significant estimate in Step 2 would mean that states with higher levels of local trust in institutions are more responsive to the monetary policy contraction, i.e. their local GDP growth slows down by more.

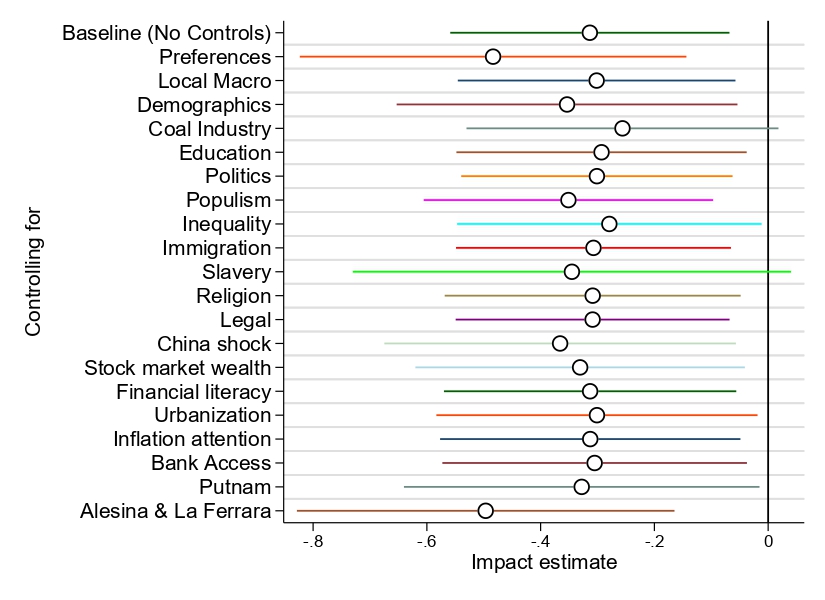

Naturally, the relationship between our regional trust measure TrustInstitutions and monetary policy could be influenced by a number of alternative variables. I therefore assemble a large array of socio-economic, demographic, and behavioral controls that could be correlated with the spatial distribution of trust. To ease the discussion, I have grouped all the controls by theme. The full list of themes that I have controlled for includes social preferences (e.g. risk aversion), local macroeconomic strength, demographics, education, political beliefs and liberalism, attention to inflation, populism intensity, wealth inequality, legal differences, stock market wealth, immigration aversion, religiosity, the scars of slavery (local slave to population ratio from the 1860 U.S. Census), the China syndrome, stock market participation, financial literacy, urbanization rate, coal production, banking access, and the Putnam (2000) and Alesina and La Ferrara (2002) existing social capital indices.

Figure 3: Trust and Monetary Policy

Note: This figure presents results from a two-step empirical procedure detailed in Section 2 of Jamilov (2023). The figure plots point estimates and 90% confidence bands from this step. The first row represents the baseline specification with no additional controls. Each subsequent row states which set of controls has been added to the baseline specification.

Figure 3 reports a key result of the study. The first row represents the baseline specification from Step 2 with no additional controls. Each subsequent row states which set of controls has been added to the baseline specification. Across the board, we observe negative and statistically significant coefficients, i.e., TrustInstitutions continues to be statistically meaningful even after taking into account additional control variables. Recall that the underlying monetary shock is a contraction. A negative estimate in the figure therefore implies that following monetary contractions local GDP growth is more negative in states with high levels of trust in institutions. In other words, monetary policy is more potent in high-trust regions. This result is robust to practically all alternative channels of causality. The only regional characteristic that appears to be relevant is the “Slavery” indicator. The legacy of slavery could have left unhealed scars in the psyche of the population: high historical slavery intensity may have contributed to lower trust in present times. More research is needed on the racial origins of modern-day distrust, political cleavages, and policy effectiveness.

Trust and U.S. Monetary Policy: Then and Now

We now revisit Figure 1 and try to answer the following question: has the rise of distrust towards institutions made U.S. monetary policy less effective over time? To this end, I build a simple New Keynesian framework with one behavioral friction: agents do not react fully to interest rate movements but exhibit distrust. In the model—as in the data—when trust is low, agents pay less attention to the monetary policymaker and underreact, i.e. monetary policy is less effective. The question is: by how much? A key parameter that governs distrust in the model is calibrated to match the observed increase in the share of respondents that answer with “Hardly Any” to the question “Do you have confidence in congress?” The calibrated and solved model predicts that the long-run (i.e. after 20 quarters) macroeconomic response to the same monetary policy surprise is 20% milder in 2023 than what it was in 1990, everything else equal. Of course, the framework is very stylized and introduces just one departure from the standard model, while the U.S. economy has gone through many, multi-dimensional changes over the same 1990-2023 period. In a richer model, the 20% number could be lower. More theoretical work is needed to quantify the macroeconomic effects of trust and social capital.

Conclusion

While my study has filled some gaps, a lot more work needs to be done to refine the social capital channel of economic policy-making. First, populism is ravaging across the Western hemisphere and the rise of populism goes hand in hand with a crisis of trust. My study can speak on this issue by conjecturing that populism can potentially affect central banking independence, potency, and behavior through an interaction with the institutional trust capital stock. More quasi-experimental work in this direction is needed. Second, firm- level surveys can potentially elicit firms’ quantity and pricing plans conditional on randomly provided (by the econometrician) policy forecasts – a kind of an institutional “trust stress test.” Such tests could also be conducted by regulators on a regular basis.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.