Do voters still believe that politics can be a source for common-good policies and not just partisan bickering and rent-seeking? With political polarization at historic levels, a new paper finds that while most voters are certainly ideological, they vote as if they believe that the policy decisions also involve common-good concerns.

Going back to at least Aristotle, democracy has been seen as a way for the people collectively to search for the “common good”— for policies that redound to the benefit of the community overall. By sharing information and deliberating as a group, democracy advocates hoped that citizens can make better decisions than any one person or clique acting on its own. In contrast, the more recent “pluralist” tradition, embodied in the US Constitution, sees democracy as an arena for competition between conflicting interests in which people and “factions” on the extreme ends check each other in the pursuit of votes, leading to compromise and centrist policies.

Today, however, democracy appears to be strangled by polarization, rendering it little more than a contest between partisans for power and rents. Many doubt that a search for the common good is even possible in today’s polarized world.

Is this gloomy picture an accurate description, or do voters still believe there is a scope for pursuing the common good in politics? One of the best-documented facts about American politics is the polarization of elected officials—are voters themselves as polarized as political elites, focused entirely on using the political system to channel benefits to themselves, or do they approach elections with a mindset of searching for a common good? These are difficult questions to answer empirically, but in a recent working paper, we develop an estimation strategy to get at them. We find that while voters are certainly ideological, they vote as if they believe that policy also involves common-good concerns.

Our basic strategy is to infer citizens‘ underlying preferences from the votes they cast on ballot measures. Unlike votes on candidates, which usually come down to a simple partisan choice between Democrat and Republican, with ballot measures we can observe how citizens react across a wide range of issues. The paper focuses on 168 California ballot propositions from 1986 to 2020. California ballot measures are an important part of governance in the state, as evidenced by the $3.4 billion in campaigning spent on them since 2000—more than twice what was spent on legislative elections over the same period.

The basic forces we want to disentangle can be seen with a hypothetical ballot measure:

Ballot Measure #1. To fund levee improvements for flood protection, and assess an income tax surcharge to pay for the improvements.

This measure has a common-benefit component—preventing the levee from breaking—that affects all citizens more or less the same way. It also has an individualized cost component that is distributional in nature: each person’s tax assessment to pay for the levy. We are interested in the question of how voters weigh the two consequences—is the common-good component important in their voting decisions, or do they focus entirely on their individualized cost? We don’t try to measure the “objective truth” of how much common-good versus redistribution is embedded in actual policies, but rather how voters perceive policies.

In order to calculate how citizens weigh the two components, we employ a technical procedure called structural estimation. The basic idea is to assume that citizens have preferences that include both components, and then search over all possible weights for the ones that best explain the data at hand. In doing this, we draw on well-established methods in political science that have been used successfully to identify ideologies, or in the example above, the distributional component.

“despite clear evidence that voters view policies through a distributional lens, they have not entirely given up on the idea of searching for common benefits.”

We find that 74 percent of citizens vote as if they place significant weight on common-good considerations. This holds across parties: both Democrats, Republicans, and Independents vote as if they perceive a common-good aspect to politics. The common-good dimension is sizeable (but not dominant) compared to the distributional dimension. In short, ordinary Americans do see politics as involving some common-good considerations, not merely as a matter of rent-seeking.

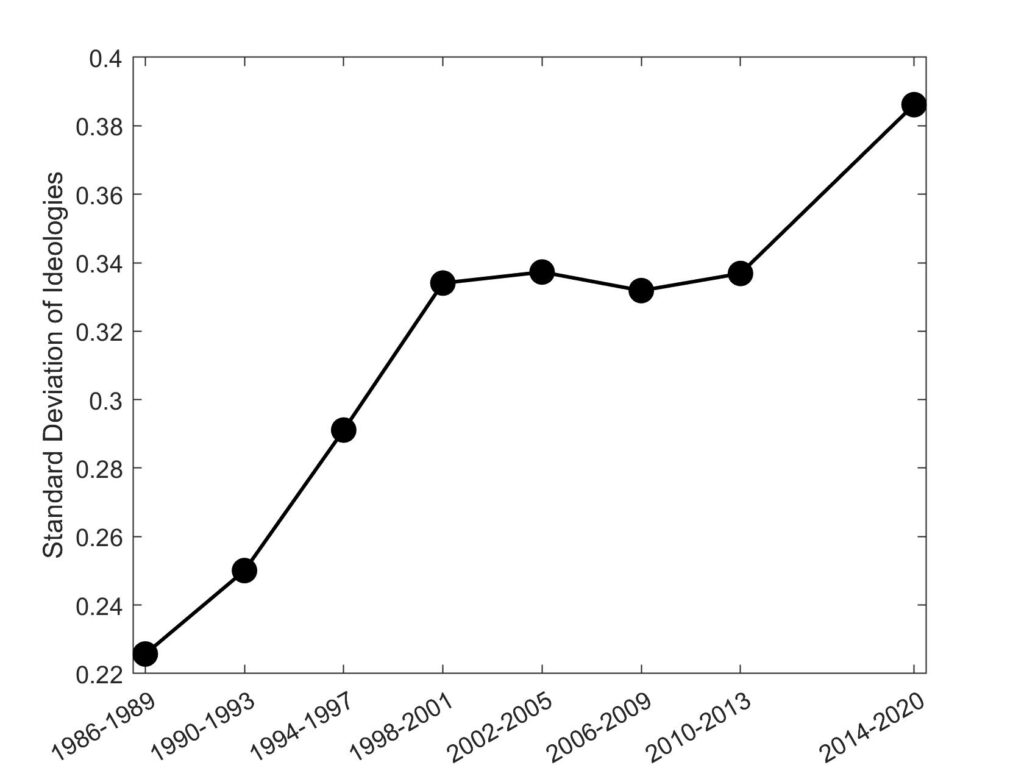

There is an enormous literature studying polarization among elected officials, showing a consistent rise in political polarization since the mid-1970s. In addition to estimates of common-good considerations, our approach produces estimates of citizen ideology and, by employing data from the post-2012 period, we are able to provide the first characterization of citizen polarization trends going back 35 years. We find that citizens have become increasingly polarized over that time, paralleling the well-documented polarization among politicians and escalating in a big way around 2010, around the time that the Tea Party Movement burst onto the scene.

The relatively late emergence of citizen polarization suggests that it has not been the primary cause of the growth in polarization among elected officials. It also raises the possibility that elite polarization itself may be causing ordinary voters to polarize. The biggest jump in polarization, which started around 2010, pre-dates the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Trump may have contributed to the polarization of the public, but it was already underway before he took office, and therefore appears to have deeper roots.

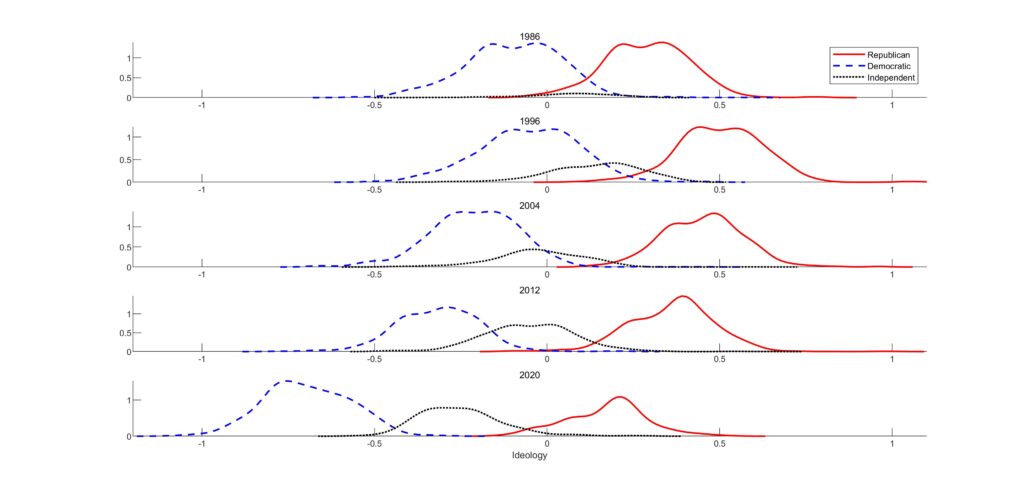

Previous research suggests that growing polarization among elected officials has been due to Republicans drifting to the right, with Democrats more-or-less holding in the same place. The following figure shows what has been happening with citizens, plotting the distribution of their (distributional) ideologies at different points in time. In every year, Democrats are to the left of Republicans, with Independents between the two. In contrast to elites, we find that the polarization among citizens is largely due to Democratic partisans moving more to the left since about 2010; Republicans in fact appear to have drifted a bit to left as well.

Our findings have limits that should be kept in mind. One is that we focus on California voters. California is a big state, and understanding its voters is of interest in its own right, but it is likely that Democrats and Republicans differ from state to state, so no single state is representative. Another limit is that we assess preferences only on issues that came to a vote in a ballot measure. Those propositions do cover a wide array of topics related to economic, governance, and social issues, including tax increases, tax cuts, primary elections, redistricting, campaign finance, same-sex marriage, capital punishment, and marijuana legalization, but it is possible that preference weights are different on other issues.

Keeping these limitations in mind, our evidence still gives some grounds for cautious optimism about democracy—despite clear evidence that voters view policies through a distributional lens, they have not entirely given up on the idea of searching for common benefits.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.