George Stigler’s “The Theory of Economic Regulation” is not just the founding paper of economics of regulation. It is also a founding paper of political economy. Before Stigler, economists thought about politics in terms of voting and the median voter theorem. Stigler’s paper taught us that the right way to think about economic policies is not just in those terms, but rather in terms of exchange between politicians and firms, or politicians and private sector actors.

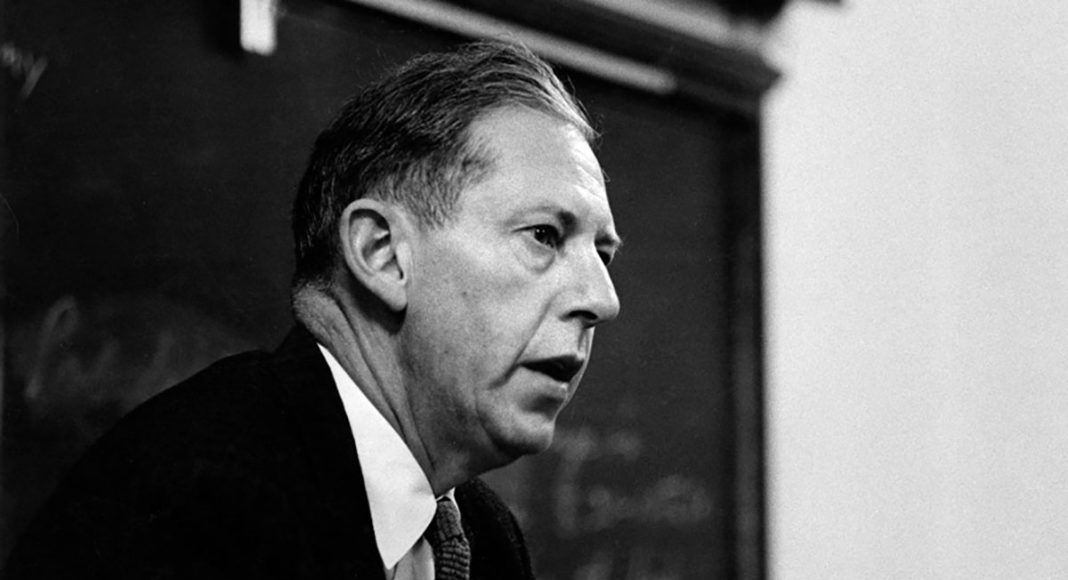

Editor’s note: In 1971, George Stigler published his article “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” To mark the 50-year anniversary of Stigler’s seminal piece, we are launching a series of articles examining his theory’s past, present, and future legacy. The series is part of the Stigler Center’s George Stigler 50 Years Later symposium. The following is based on a keynote talk Andrei Shleifer gave during the symposium.

I would like to make three points. The first point is that George Stigler’s paper is understood by all of us as the fundamental—and probably the single most important—contribution to the economics of regulation because it changed the perspective of the field. Before Stigler, regulation was seen as a policy pursued by a benevolent government to cure market failures. Stigler showed that the government is far from benevolent and that, in fact, regulation is acquired by the industry to protect its market power.

This idea has been confirmed, illustrated, and used productively to analyze regulation in many instances. But Stigler’s is not just the founding paper of economics of regulation—it is also a founding paper of political economy. Before Stigler, economists thought about politics in terms of voting and the median voter theorem and other similar ideas. Stigler’s paper taught us that the right way to think about economic policies is not just in those terms, but rather in terms of exchange between politicians and firms, or politicians and private sector actors.

On their end, politicians provide policies that benefit particular constituencies, whether it is firms or groups of voters, and whether they use regulatory policy, or protection, or just direct financial benefits. In exchange, politicians get something from those they regulate. What is that something? Of course, in some instances, it’s going to be votes from their favored entities. But there are many other forms of payment, such as campaign contributions or campaign cash. Thinking about this fundamental exchange came out of Stigler’s work. Revolving doors—whereby politicians come and take up jobs at the firms they regulate—is another form of payment. Perhaps most interesting, the Stigler perspective suggests that one way in which politicians get something in return for their policies is bribes.

Much of the economics of corruption, which has actually become quite a significant industry in economic research with a great deal of empirical evidence, is based on this Stiglerian idea of exchange between politicians and firms, which is to say some of what politicians get in return for favorable policies are in effect bribes. There is no denial of the empirical significance of that idea.

In the original Stiglerian conception, the initiating parties of regulation are the firms that seek protection from politicians. Of course, that’s not always the case. You can flip the argument around, which is a lot of what we see in the world and in the data, and see politicians initiating burdensome regulations and then collecting favors or bribes or money in return for relief from regulation. Some years ago, I was part of a project on the regulation of entry by small firms around the world. In this setting, it became very clear that one of the reasons for this regulation is precisely for politicians to be able to extract bribes in exchange for relief. And so again, this Stigler-inspired line of work that led to many things, including the World Bank’s “Doing Business Report,” which empirically describes—in many spheres of economic activity and around the world—the consequences of the very broad Stiglerian idea of exchange between politicians and the entities they regulate. I give Stigler an enormous amount of credit for directing political economy toward this goal.

“It’s a mistake to think that all bad regulatory or economic policies come from the Stiglerian exchange or from capture. In many instances, ideology, ignorance, or narrow objectives play a big role.”

The second point I want to make is that although I think that Stigler’s is probably the single most important reason for bad economic policies, or regulatory policies, there are other key reasons: regulator ideology, regulator ignorance, bad ideas, regulators’ narrow mission. It’s a mistake to think that all bad regulatory or economic policies come from the Stiglerian exchange or from capture. In many instances, ideology, ignorance, or narrow objectives play a big role. I’m going to illustrate this with some ideas from the fight against Covid. And I want to stress that both the left and the right are culpable.

Let’s start with President Donald Trump’s Covid denialism and aggressive policies against masks, against testing, and so on, which probably have cost the United States tens of thousands of lives, and maybe millions of infections. Now, you can make the argument that somehow Trump was trying to exchange these policies for votes. But that argument seems to me to be a bit strained, in the sense that you could have perfectly imagined a patriotic appeal to voters that would, in fact, seek support for the rapid ending of the Covid. Yet none of that happened. Why? Well, it seems to me that we can take the evidence at face value that the people around the president, and the president himself, were ideologically motivated to deny the dangers of Covid and wished to pursue policies that turned out to be pretty damaging. I think of this as an instance in which you can argue from both the Stiglerian and the ignorance perspectives, although I would guess the latter played a big role.

As another example, consider the European Union and the acquisition of vaccines. I don’t have any insider knowledge on this, but it seems to be pretty obvious what has happened: the task has been allocated to the EU procurement agency, which felt that their goal was to get the best price. They did get very low prices, but also got subcontracts that had the best efforts nature, which basically meant that when there were higher bids from elsewhere, there were no vaccines for the European Union. My point is that this is not a Stiglerian exchange: This is an atrocious policy that has caused the European Union hundreds of billions of dollars in lost output and probably thousands or tens of thousands of lives. This is not capture. It’s pure incompetence, but the source of that incompetence, I think most likely, is just narrow incentives of the bureaucracy to get the best price, rather than to think about the costs of delay. Bad policies come from incentives and ignorance, not capture.

Just to be fair to the Europeans, let’s consider the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) slowdown and temporary stop of the use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine after seven million doses, seven episodes of blood clotting, and I believe one death—a policy that will surely cause tens of thousands of additional infections and maybe a few deaths. What is driving this? Is it capture? Is it the efforts by the competitors? No, it’s not that. Rather, it’s rather that the FDA bears no consequences if thousands of extra people get infected but suffer severe consequences if a couple of extra people die. And so you have tremendous distortions in regulatory policies resulting from bad incentives in the public sector, rather than from capture per se.

The $15 minimum wage is another moment of intended self-inflicted damage. Almost a third of the working people in the US make less than $15 an hour. Some of them work for the large and profitable firms that may be able to sustain the wage increases, the stereotypes produced by the advocates of the policy. Probably half of the people who make less than $15 an hour work for extremely unproductive firms that are going to have to close—there is no way in which they’re productive enough to pay those wages. In fact, the chain restaurants and large retailers will probably benefit from the closure of their small competitors. Raising the minimum wage sharply strikes me as a purely ideological approach, which is likely to be harmful. Again, I don’t think that capture is the right theory.

One last example of this is that often capture interacts in an interesting way with ideology. My favorite example comes from the work of Harvard PhD student Josh Hurwitz. Between 1987 and 2017, over a 30 year period, the number of fires in the United States has fallen by 43 percent and the number of firefighters has increased by 54 percent. If you look at the UK, the number of fires has fallen tremendously as well, but so has the number of firefighters. How can this happen in the US? It is not because firefighters prevent fires. Firefighters don’t prevent fires—they extinguish them. So what is happening? Well, it’s a combination of capture and ignorance.

Today, firefighters in the United States do not just fight fires; they also race ambulances to be the first ones to arrive for 911 health emergency calls. If you actually do the calculations, the benefits of this for lives saved are negligible, if any, mostly because fire trucks typically come second, but also because the vast majority of 911 calls are not a matter of life and death, and definitely not a matter of a few seconds. In the meantime, the costs of this increase in the number of firefighters are billions of dollars that municipalities could be spending on schools. A truly bizarre policy, based on superstition rather than evidence. But this is where Stigler comes in: Once these policies were put in place by people who didn’t really understand the facts and the data, they are now extremely strongly supported by firefighter unions and impossible to get rid of. So it’s the combination of bad ideas and capture that sustains bad policies.

“Stigler’s is not just a great paper; it is also living paper. It’s a paper that even today, 50 years after its publication, provides intellectual inspiration.”

The last point I’m going to make is that there is another line of thought that Stigler’s work has started. It is probably not what Stigler intended, because it seems to me that a lot of regulations are in fact extremely useful. Even though we do see distortions in regulatory policy, it is also the case that in a civilized society, we’re used to having many regulations that we think are on net beneficial. We like flying on safe planes. We like that the food that we eat is safe. We like that the water we drink and swim in is clean. We like that the air that we breathe is less polluted. We like to drive safe cars.

Now, you can say that the market would have taken care of those problems, but it would be wrong to say that, because we have plentiful evidence from early 20th century US, as well as specific evidence from cases of water and air pollution, that markets do not take care of many problems. You can say that the courts would have taken care of market failures, but that also would be wrong. In many situations, the courts fail to cure market failures, either for ideological reasons, but also because in litigation, in many instances, firms tend to be much more powerful, much richer, have better lawyers, and better resources to subvert justice than the affected consumers or employees. And so, in fact, both historically, regulation, more often than not, is actually an efficient response to failures in the marketplace.

This is, in some sense, an argument that takes you away from Stigler. But, in another sense, it is something that Stigler and Harold Demsetz should get a tremendous amount of credit for because in order to think about economic policy, we need to focus on alternative solutions to the problems of market failure. In many cases, it is the most efficient solutions, including regulation, that survive the competition with others. And so, it seems to me that even that way of thinking, which is pretty central to many of the ideas in law and economics, owes a lot to George Stigler. Ed Glaeser and I have been pursuing these ideas for the last 20 years, and we owe a great intellectual debt to Coase, Demsetz, and, of course, Stigler.

Stigler’s is not just a great paper; it is also living paper. It’s a paper that even today, 50 years after its publication, provides intellectual inspiration. Even when one disagrees with it, it opens up avenues for going in new directions, for exploring the world that we live in. For this, we should all be extremely grateful and appreciative.