The House Judiciary Committee’s antitrust report was a missed opportunity. The 450-page report focused solely on digital markets. But what about antitrust in other sectors such as food and healthcare?

The House Judiciary Committee’s long-awaited report on competition in digital markets was underwhelming to say the least, as I detailed in a recent piece for MIT Technology Review. The report did not make a convincing argument that the tech giants have monopolized markets or squelched new entrants (see Shopify, TikTok, and Zoom). Most importantly, it did not find evidence that overturns the most relevant fact about competition in tech: prices keep going down.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, between December 1997 to September 2020, the consumer price index rose by 61 percent. During this time, the price of books fell by two percent and music fell by 18 percent. Prices for telephone hardware, calculators, and other consumer information items (half of which is accounted for by cellphones) fell by 86 percent. Between December 2009 and June 2020, the price of online display advertising fell by 35 percent and the price of search and text advertising fell by 62 percent (the overall price index rose by seven percent during this period).

Of course, that doesn’t mean tech hasn’t contributed to devastating social problems, including privacy issues, misinformation, hate speech, and election interference. These are clear market failures—negative spillovers not internalized by the platforms—that need targeted regulatory solutions. But, importantly, these problems can’t be solved using the antitrust hammer. Many of the problems ascribed to tech companies are the result of too much competition rather than too little. When Amazon sells a store brand product that resembles a brand name good, that’s more competition. When Apple adds a new feature to the iPhone that replicates functionality from a third-party app, that’s more competition. When Microsoft adds a new software service to Office 365, that’s more competition.

If economic analysis reveals that this level of competition reduces innovation in the long run, then the appropriate regulatory intervention is to reform the intellectual property laws, which are designed to restrict competition, not to change the antitrust laws.

Starting Off on the Wrong Foot

It’s a shame the House Subcommittee on Antitrust chose to spend more than a year investigating digital markets when there are many other sectors crying out for greater antitrust. If legislators wanted to look into industries where there was the highest likelihood of consumer harm, they should have started by asking where prices have increased most rapidly in recent decades (and which are essential for American consumers).

“It’s a shame the House Subcommittee on Antitrust chose to spend more than a year investigating digital markets when there are many other sectors crying out for greater antitrust.”

Of course, it’s possible that prices could have fallen even faster in digital markets under certain counterfactual scenarios (and perhaps future antitrust cases against Google and Facebook will show that). But it remains odd to target our most globally competitive and innovative companies when prices in food and health care have been rising faster than overall inflation. Those industries have serious competition issues that are worthy of much more investigation.

Food

As Christopher Leonard wrote in his book The Meat Racket: The Secret Takeover of America’s Food Business, “Four companies make 85 percent of America’s beef and 65 percent of its pork. Just three companies make almost half of all chicken.” Market concentration alone is not conclusive evidence of a competition problem. Large companies can achieve their dominance due to economies of scale or by virtue of creating the best product in the market. However, it is an antitrust violation to secure market power via anticompetitive conduct and use that power to harm consumers.

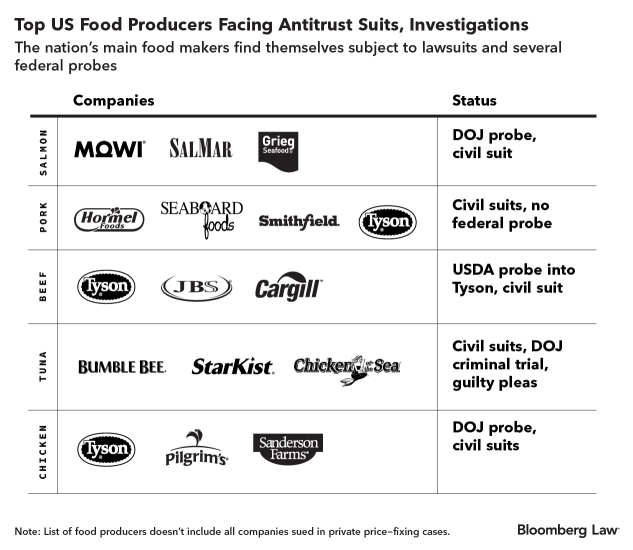

And the food processing market has seen a number of high-profile antitrust cases recently: Executives from multiple large chicken producers were indicted in June by the Department of Justice in a price-fixing case. Around the same time, the DOJ issued subpoenas to the four biggest beef processors as part of an antitrust investigation. Also in June, the former CEO of a canned tuna company was sentenced to 40 months in jail for his role in a multiyear conspiracy to fix prices. In November of last year, a group of pork consumers brought a class action antitrust lawsuit against the leading pork producers, claiming they conspired to raise prices over the last decade.

Last year, a Bloomberg Law article collected all the ongoing antitrust probes in meat markets (see table below). The piece was titled “Turkey Remains Rare Meat Not Embroiled in Antitrust Probes.” Ironically, as Austin Frerick pointed out less than a month later, it was announced that the turkey industry was also under investigation: “This means that ALL major American proteins have some sort of price-fixing investigation in the works.”

Why might price-fixing suddenly be such a problem in the food industry? In conjunction with massive consolidation in the agricultural industry over the last few decades, new companies such as Agri Stat now offer industry insiders access to proprietary information about their competitors’ sales, production levels and capacity, and wages paid to farmers. The data is anonymized, but many on the inside claim it’s easy to know which data comes from which producer. With fewer players and better data on production costs, colluding is easier than ever before (and it’s also potentially easier to know when a member of a cartel has defected).

Competition issues in the food processing market writ large have been brought to the forefront by the pandemic. Consumers are hurting. Between March and June, prices for meats, poultry, fish, and eggs increased more than 10 percent while overall prices remained flat. Workers are doing even worse. Slaughterhouses force employees to work in tight quarters at cold temperatures with limited personal protective equipment. Workers are disproportionately immigrants, which makes them less likely to speak up when they feel unsafe. The pandemic is only exacerbating these underlying issues. Because the food processing industry is heavily centralized, a viral outbreak in one or two facilities can ripple throughout the supply chain. The US needs more competition in this market not only to lower prices for consumers but also to improve conditions for workers and make the system more resilient to supply-side shocks such as public health crises.

While it’s encouraging to see so many antitrust cases being brought against food producers, the breadth and scope of the suits suggest there are systemic competition issues at play that would warrant Congressional hearings of their own. I can only speculate about the causes and the extent of these problems because Congress didn’t spend the past year writing a 450-page report on the agricultural industry. It would have been preferable if they had.

Health care

The health care industry is also rife with competition issues, many of which are exacerbated by poorly designed regulations, which are often implemented at the behest of rent-seeking incumbents. Pharmaceutical companies have been charged in numerous “pay-for-delay” antitrust cases, paying generic drug producers to not compete with branded drugs. The generic drug market has also seen producers colluding to carve up the market and reduce competition. On the insurance side, Blue Cross just settled an antitrust suit for $2.7 billion after being accused of anticompetitive behavior. But perhaps no sector of the healthcare industry has been as problematic as the hospital sector.

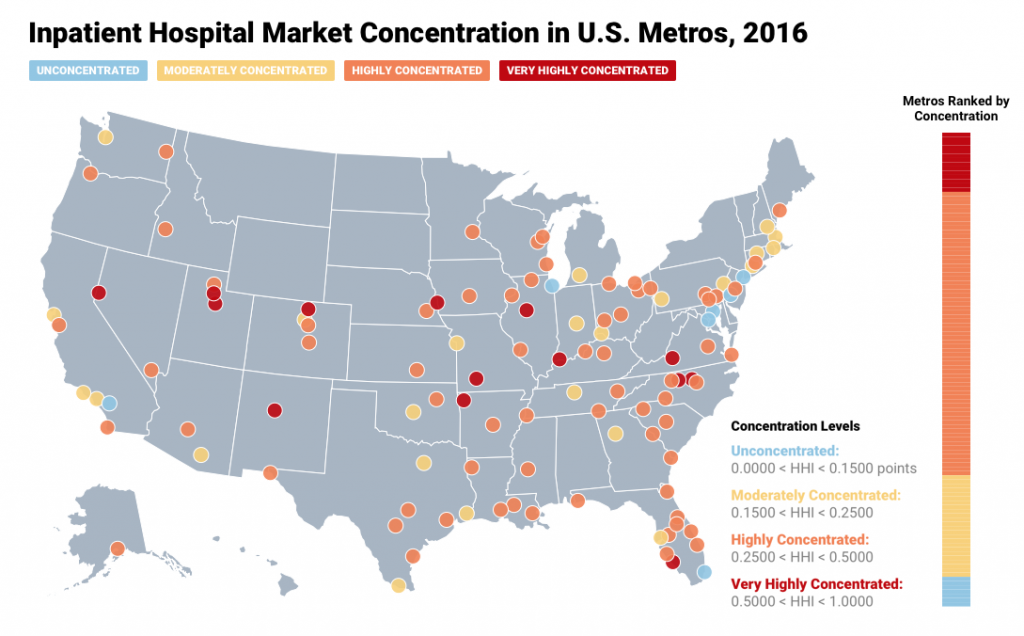

Hospitals are highly concentrated in the US. As Avik Roy noted, “In other industries, such as airlines or cell-phone carriers, the FTC routinely seeks to block mergers that would increase HHI scores above 2,500. In the hospital industry, however, the median market HHI exceeded 2,500 in the year 2000, and reached 2,800 in 2013.”

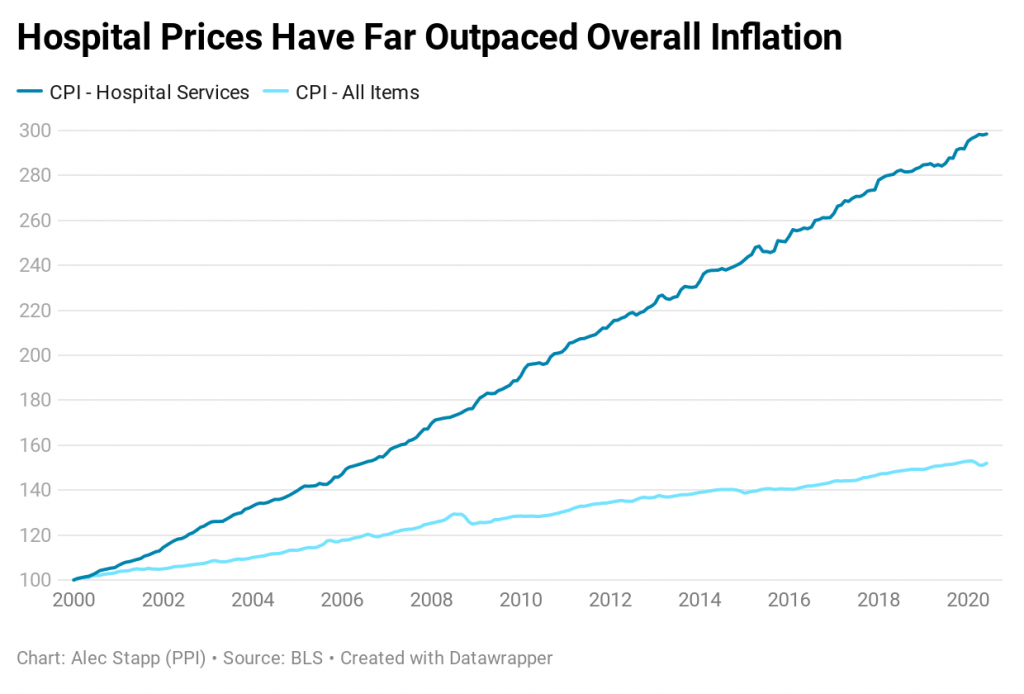

Rising concentration has likely contributed to the fact that prices of hospital services have nearly tripled over the last 20 years. By comparison, overall prices—as measured by the consumer price index (CPI)—have increased about 50 percent.

The cause of this price spiral in hospital services is multi-faceted, but regulation and lack of competition are large factors. In many states, certificate of need laws mean that local hospitals effectively have a veto to block competitors from entering their market and offering a better deal. Occupational licensing and scope of practice laws also increase labor costs in the healthcare market with unclear benefits for consumers (nurse practitioners and physicians assistants are highly capable and currently underleveraged by our healthcare system).

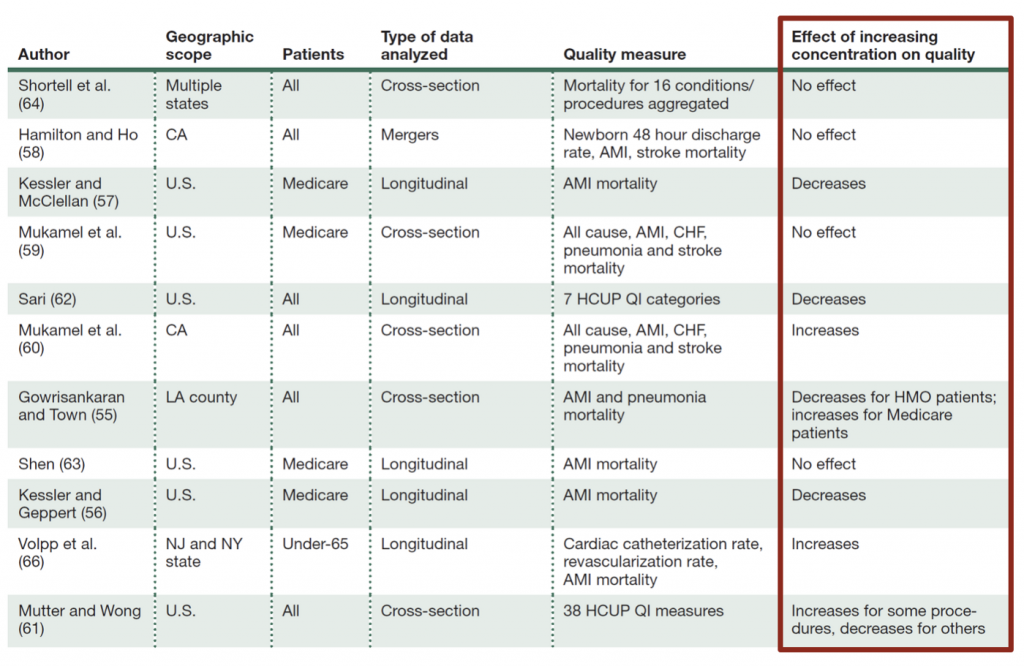

The classic antitrust defense in this scenario—when both concentration and prices are increasing—is to say that increases in service quality more than offset the price increases. But a meta-analysis of 11 studies in 2006 found little to no evidence that increasing concentration increases quality.

Moreover, earlier this year, a study in The New England Journal of Medicine of 246 acquired hospitals and 1,986 control hospitals found that “hospital acquisition by another hospital or hospital system was associated with modestly worse patient experiences and no significant changes in readmission or mortality rates.” These findings throw cold water on the idea that, while prices for hospital services may increase following mergers, service quality also increases. If anything, this new data shows that service quality decreases, as measured by patient experiences.

As with the food processing plants, the Covid crisis has put a spotlight on weaknesses in our hospital system. Hospitals in virus hotspots—including New York City, Los Angeles, and Texas—have been pushed to the breaking point. Of course, even a competitive hospital market wouldn’t necessarily be able to seamlessly handle a surge in patients during a pandemic. But the hallmark of monopolistic behavior is to raise prices and reduce output. It stands to reason that having more hospital providers in more markets would increase total capacity and make the system more resilient in the face of a crisis.

Some of the best policy ideas for promoting competition and price transparency can be found in recent papers by Martin Gaynor for the Brookings Institution and Avik Roy for the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity. Here are some good ideas:

- Repeal (or scale back) “any willing provider” laws and network adequacy mandates, which limit insurers’ ability to bargain effectively with high-cost hospitals.

- Limit the use of Certificates of Public Advantage (COPA), which provide an antitrust exemption for anticompetitive mergers under the dubious expectation that future conduct will be more tightly regulated.

- Require hospitals to publish the cost of their most 100 common services.

- Reform scope of practice laws and provider licensure requirements.

- Create a national all-payer claims database (APCD), so insurance providers and employers can better track costs and bargain effectively.

- Authorizing funding for a 400 percent increase in FTC staff working on hospital mergers.

- Facilitate more medical tourism and telemedicine via reference pricing and harmonization of state medical licensing.

Conclusion

Even if you’re not persuaded that the state of competition in digital markets is optimal, we should at least be able to agree that other sectors of the economy have clearer and more urgent antitrust problems that deserve to be prioritized. Instead of focusing on Big Tech, the House Antitrust Subcommittee should have spent its scarce time and resources investigating the food and health care industries (and other sectors inflicting obvious consumer harms). The same can be said for the DOJ, the FTC, and the state attorneys general, all of which have jurisdiction over antitrust issues. Breaking up monopolists and blocking future mergers in the food and health care markets won’t fix the competition problem completely—we also need regulatory improvement—but it is a good step toward creating a more resilient economy.

Disclosure: Alec Stapp is the director of technology policy at the Progressive Policy Institute, a think tank whose donors include Amazon, Facebook, and Google.