Purdue’s strategy was to market its opioids directly to patients via brochures, videos, advertisements, and the internet. It also provided information to doctors and consumers through an apparently independent entity called “Partners Against Pain,” but ultimately controlled by the company itself.

Editor’s note: This piece is the third of a series of three on Purdue’s market strategies to promote one of the most well-known opioids, OxyContin. You can read the first two articles here and here. The series is based on edited excerpts from “The Marketing of OxyContin®: A Cautionary Tale” by David S. Egilman, Gregory B. Collins, Julie Falender, Naomi Shembo, Ciara Keegan and Sunil Tohan, published on the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, Vol IV No. 3, July-September 2019.

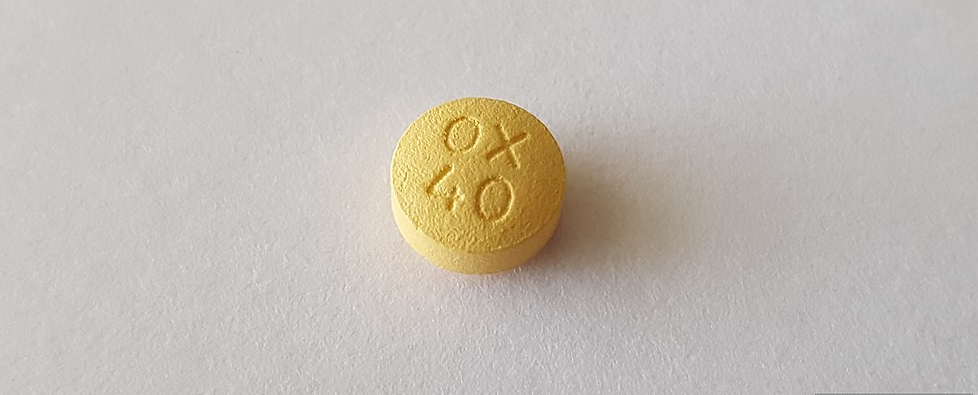

The Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) was concerned that Purdue had used its label to inappropriately broaden the indications for use of OxyContin while understating the risks of abuse. After negotiations with the FDA, Purdue revised its OxyContin label in 2002 to include a black box warning—the strongest warning found on prescription drugs—regarding abuse risks, and a new section on “Misuse, Abuse, And Diversion of Opioids.”

The company saw the change as an opportunity to further “broaden OxyContin Tablets usage in the management of pain,” with special emphasis on post-operative pain. The black box warning stated that OxyContin should be restricted to patients “with moderate to severe pain when a continuous, around-the-clock analgesic is needed for an extended period of time.”

Purdue’s 2002 budget plan explained how they intended to take advantage of this new language, “The action taken by the FDA to clarify the OxyContin Tablet labeling has created enormous opportunities. In effect, the FDA has expanded the indication for OxyContin Tablets to any patient with moderate to severe around the clock persistent pain…” This moved beyond post-operative patients to simply any patient with pain. The budget plan went on to proclaim that, “This broad labeling is likely to never again be available for an opioid seeking FDA approval. This may give OxyContin Tablets a competitive advantage.” Thus, Purdue seized on the FDA label change to expand the market for OxyContin, a Schedule II opioid narcotic, as a first-line agent for the relief of moderate pain, a distinction previously reserved for Schedule III and IV narcotics and non-Scheduled alternatives like NSAIDS and Tramadol. This marketing strategy, promoted to prescribing physicians, further increased the risk of addiction for patients.

Purdue directed a great deal of its marketing directly to patients via brochures, videos, advertisements, and the internet. It provided information to doctors and consumers through an apparently independent entity called “Partners Against Pain,” claimed to be an “alliance of patients, caregivers, and health care providers,” but actually an “Astroturf,” or fake grassroots organization. Purdue published and copyrighted the “Partners Against Pain” website, and the written materials on the site represented the interests and viewpoints of its owner.

For example, a “Frequently Asked Questions” booklet available from the site, titled “A Guide to Your New Pain Medication and How to Become a Partner Against Pain,” reassures readers that OxyContin only rarely presents an addiction risk. One question asks, “Aren’t opioid pain medications like OxyContin Tablets ‘addicting’? Even my family is concerned about this.” Purdue proffered the following misinformation as its answer: “Drug addiction means using a drug to get “high” rather than to relieve pain. You are taking opioid pain medication for medical purposes. The medical purposes are clear and the effects are beneficial, not harmful.”

This “guide to patients” misleads patients into believing that their motivation for taking OxyContin (ie, for pain instead of to “get high”) is the major determinant of whether they are, or will become, addicted to the medication. Yet, as is the case with all opiates, some patients will become addicted even if they initially used the drug to relieve pain and not to “get high.” There is no scientific support for the notion that the user’s motivation for initially using opiates determines whether he or she will become addicted later.

In 2001, in another question and answer section of the “Partners Against Pain” website, Purdue declared: “When you feel pain, your pain is real… Remember: You have every right to ask [doctors and nurses] to help you relieve the pain as much as possible. By implying that patients have a right to as much pain relief as they wish without any regard for prescriber objections or for possible adverse reactions, Purdue encouraged patients to demand its drug and propagated misinformation about pain perception and risk of addiction.

In 1986, the World Health Organization developed practice guidelines for cancer pain management and recommended that treatment begin with non-opioid analgesics. Purdue cited the WHO guidelines in its own marketing materials; however, Purdue also used the marketing “the one to start with,” misconstruing the WHO’s guidelines and positioning OxyContin as the first drug of choice for pain.

Purdue’s pamphlet and informational video, both titled, “From one pain patient to another,” encouraged patients to doctor-shop to find providers who were most willing to prescribe narcotics. Patients were told, “Don’t be afraid about the things you’ve heard about these drugs [opioids],” and, “…find the right doctor.” One “patient” featured in the video remarked, “I think it is very unfortunate that so many physicians are reluctant to treat people like me, who have moderate chronic pain, with opioids.” Another patient was shown being treated with 1200 mg of OxyContin per day! Purdue thus disparaged the more cautious prescribing practices of responsible health practitioners who approached this drug as potentially addictive.

The OxyContin case raises important questions of industry accountability and responsibility in the production, marketing, and sale of potentially dangerous drugs and narcotics. Proper, appropriate, balanced, complete, and scientifically valid information must be in the hands of physician “learned intermediaries.” Direct-to-consumer marketing can circumvent physician judgment and cautious risk-avoidance in medication prescribing.

Purdue Pharma, in its relentless zeal for sales growth and profits, abdicated its responsibility by subverting governmental regulatory authority, and by repeatedly and systematically misinforming prescribing doctors and the public about the characteristics and inherent risks of its Schedule II narcotic, OxyContin. This case demonstrates that physicians who prescribe narcotics for pain need to be vigilant for self-serving, invalid, or unbalanced claims in their review of advertisements and corporate sales promotions for drugs, especially those, like OxyContin, with potential for abuse, diversion, addiction, overdose, and death.

Companies have an obligation to stockholders to maximize profits by increasing revenues and by minimizing or avoiding costs, including social costs and the costs of adverse reactions to their products. They are not self-regulating entities. Physicians need to be aware that these business imperatives can drive marketing practices which are not scientifically or ethically based, and which may be based on flawed or untested clinical assumptions.

Statement of Conflict of Interest:

David Egilman has consulted on opioid litigation at the request of addicted patients and counties. Gregory Collins has consulted on opioid litigation at the request of addicted patients. DE is the owner of Never Again Consulting; NS, CK, and ST were compensated by Never Again Consulting for their contributions.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.