Amazon’s price matching policies, which were meant to ensure its dominant position, diminished the ability of brands to control how their products are distributed and the prices at which these products are sold, writes Shaoul Sussman.

Earlier this month, Federal Trade Commission chair Joe Simons said that the FTC is interested in hearing complaints from sellers punished by Amazon because they offered cheaper deals on other websites. “Anyone who wants to complain, we’re all ears,” said Simons.

In a paper published this year and in subsequent pieces published in this blog, I made the argument that Amazon may have engaged in predatory pricing to build its consumer and supplier base, and that a well-publicized supplier purge that took place in March might indicate the company has already entered the recoupment phase. I speculated that during the predation phase, Amazon sold products as a first-party to consumers on its platform at below average variable cost and that Amazon recently began to recoup its losses by shifting the bulk of the transactions that occur on the website to its marketplace, where millions of third-party sellers pay hefty fees that enable Amazon to take a deep cut of every transaction.

Amazon’s current marketplace policies and fees are now harming third-party sellers, whether they are actual brands or authorized distributors who struggle to operate their businesses on the platform. These harsh marketplace pricing policies not only squeeze the sellers but also result in higher consumer prices across the retail industry. But it appears that consumers and third-party sellers are merely the collateral victims of Amazon’s business practices, which seem to be primarily designed to gain and increase control over the brands and manufacturers that consumers desire.

Based on conversations I held with former employees, sellers, and brands following the publication of my paper, I argue that if Amazon engaged in predatory pricing, its conduct not only cemented its role as the primary destination for consumers that shop online but also helped it solidify its power over brands. Amazon, I believe, was willing to go to great lengths to ensure brand availability and inventory, including turning to the grey market, recruiting unauthorized sellers, and even selling diverted goods and counterfeits to its customers. This, in turn, diminished the ability of brands to control how their products are distributed and the prices at which these products are sold.

In order to understand how Amazon was able to achieve such dominance over brands, it is necessary to shift our focus from the sellers and trace the journey of a typical brand on the platform during the predation and recoupment phases.

The Predatory Stage

Traditionally, retail brands have had significant control over the distribution of their products and, subsequently, over quality control. However, the rise of e-commerce has ushered in a new era. Globally, brands gradually observed that the emergence and proliferation of online retail loosened their ability to control the distribution and therefore guarantee the quality of their products. At times, retail websites would sell branded products without a valid warranty or would claim that a given product was new when it wasn’t. Similarly, the growth of eBay and similar websites posed an additional threat: the proliferation of counterfeits and knockoffs.

As a result, brand owners began to enforce what’s known as Minimum Advertised Price (MAP) policies, which effectively set the lowest price that can be publicly displayed for a product on sale and ensure that their seller network does not advertise products below that set price. Retail brands began implementing these policies with their sellers and distributors to ensure uniform pricing across both online and brick and mortar outlets. MAP policies allowed brands to quickly trace leaks in their distribution networks and crack down on sellers who sold counterfeit or damaged merchandise (these pricing policies were also effective in disincentivizing unauthorized sellers). In addition, these policies were crafted to avoid the potential antitrust implications that more aggressive resale price-maintenance schemes could have.

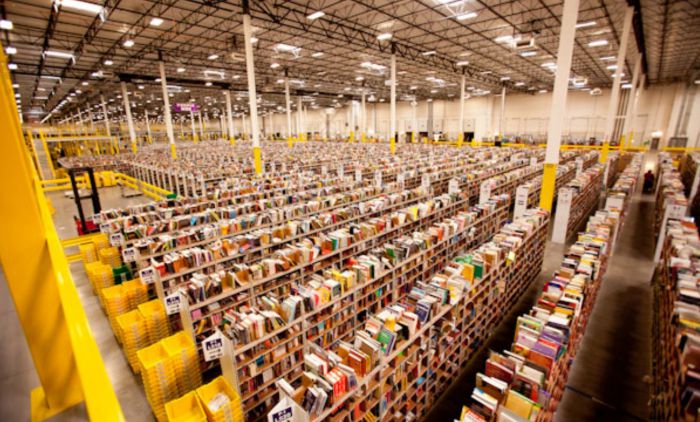

Enter Amazon. By now, it’s common knowledge that Amazon played a crucial role in disrupting the retail industry and revolutionizing consumer habits. But the company’s influence over how products are distributed to consumers has been less publicized and, until recently, less apparent.

Amazon’s power did not manifest itself immediately, even to the brand owners who dealt with the tech giant directly. At this early stage, brands were convinced that the restrictions imposed by MAP policies would effectively constrain the ability of platforms like Amazon to undermine their control over product distribution. Therefore, many brands voluntarily began to sell their products through the emerging platform. Some joined as sellers on the marketplace, others chose to sell their products through authorized third-party sellers, and some began to sell their products directly to Amazon.

But Amazon had an ace up its sleeve. My sources indicate that the company deliberately turned to and empowered the “grey market“—where both genuine, authentic goods and knockoffs are purchased and resold outside of brands’ intended distribution pipes—to dominate certain brands. In the course of my conversations with former Amazon employees, some reported that Amazon actively sought out and recruited unauthorized sellers as both third-party sellers and first-party suppliers. Being unauthorized, these sellers were not bound by the brands’ policies and therefore outside the scope of their supervision.

According to these accounts, Amazon would encourage unauthorized sellers to join the marketplace and start selling the products of a given brand—typically at a lower price than authorized sellers, who operate with higher margins and who sold products through other channels. According to one account, vendor managers—Amazon employees who manage the accounts of brands that Amazon sells directly to consumers—were encouraged to actively recruit these unauthorized sellers. They would typically offer large unauthorized third-party sellers who peddled in diverted or counterfeit products to become official Amazon partners by providing them with Vendor Central Accounts, which transformed them into suppliers who sell to Amazon in bulk. This enabled Amazon to sell grey market goods—including, in some cases, counterfeits and knockoffs—directly to consumers.

Even more surprisingly, former employees claim that at times Amazon would sell those diverted products at below acquisition-cost. These activities effectively limited the ability of brands to ensure that their goods are sold on the platform only through their authorized sellers. Additionally, it also limited the ability of brands to control the price at which their goods were advertised.

Some brands became aware of these practices and were therefore reluctant to join the platform, refusing to sell their products through Amazon. But these attempted boycotts were all but destined to fail. It appears that these brands were de-facto forced to sell through the e-commerce titan: even if a given brand refused to deal with Amazon directly and prohibited their authorized sellers from joining the platform, that brand would nonetheless notice that their products were sold by unauthorized sellers. Former employees claim that Amazon circumvented the attempted boycotts of these reluctant brands by actively recruiting unauthorized sellers who sold branded products without authorization. This effectively forced reluctant brands to the negotiation table. Even though they did not wish to sell on the platform at first, brands such as Birkenstock ultimately determined that it was better to cooperate with Amazon than to watch grey market sellers selling their products or knockoffs on its platform without their consent.

At this point, it is necessary to explain why brands were largely unable to block these unauthorized sellers and effectively resist Amazon’s efforts to undermine their control over product distribution. The short answer is that it is almost impossible for a brand, even one as dominant as Nike, to effectively crack down on unauthorized sellers that sell via Amazon. Despite the scant case law on this matter, court records reveal the modus operandi of unauthorized sellers on the Amazon marketplace.

As the Colorado District Court recently explained:

“In recent years, there has been an increase in the amount of retail sales completed through online marketplaces, such as Amazon. These online marketplaces allow third party sellers to sell a manufacturer’s products anonymously. It has been well publicized that unauthorized third-party sellers sell diverted products through the online marketplaces, including damaged, defective, tampered-with, and/or fake products. Because these third-party sellers operate anonymously, a manufacturer has no ability to exercise its quality controls over the products or to ensure the products are safe, which presents serious risks to consumers.”

In addition, the court observed that unauthorized sellers online typically operate beyond the reach of American authorities, thereby alleviating the most severe potential repercussions of their unauthorized or illegal activities. And even if at times Amazon complies with a given brand’s request to remove an unauthorized seller for the marketplace, the effects of removal are usually temporary and minimal since other, almost-identical sellers would begin to sell their products within days. In some cases, Amazon does not comply with brands’ suspension demands on various grounds, or simply ignores them. Brands can then file a trademark infringement lawsuit against the unauthorized seller in order to force Amazon to suspend it. But even when a brand obtains a judgment against the seller and a court orders Amazon to terminate the account, another one will usually take its place within days.

All of this does not mean that Amazon is unwilling or unable to solve the problem it created in the marketplace. Last year’s well-publicized agreement between Apple and Amazon, now under scrutiny from the FTC, seems to reflect the future relationship between Amazon and the brands on its platform. For years, the Amazon marketplace was plagued with unauthorized sellers who peddled in Apple products or sold counterfeits. In this unruly reality that Amazon created and fostered, even a tech giant like Apple could not effectively control the prices and distribution of their products. The only option left for Apple was to turn directly to Amazon for assistance. In exchange for certain concessions, Amazon began to “gate” Apple’s products on the marketplace, purging all unauthorized dealers from the marketplace upon Apple’s request. Most recently, it was rumored that Garmin has entered into a similar agreement with Amazon.

The damage to brands as a result of all of this is twofold: First, many brands suffered from price erosion due to the sale of cheaper counterfeits and used products, as well as unauthorized sales not bound by MAP policy, and are willing to operate with lower margins. Since the unauthorized sellers and even Amazon itself offered the brands’ products on the platform at a lower price, the revenue of the brands’ authorized sellers significantly declined both in the Amazon marketplace and in other websites or brick and mortar stores.

Second, as a direct result of Amazon’s assault on the brands’ control, authorized sellers started to push back. Many authorized sellers argued that the brands are effectively penalizing them by forcing them to adhere to the pricing policy. This made it increasingly difficult for brands to attract, recruit, and retain authorized sellers.

Overall, it appears that there is a direct correlation between these activities and the theory that Amazon is engaging in predatory pricing. By offering products at below-cost and enabling the activities of unauthorized third-party sellers, Amazon not only attracted more users to the platform—it also deeply disrupted the retail business by undermining the traditional roles of brands in the market. This state of affairs, which Amazon helped perpetuate, is also a business opportunity: Amazon now has a program that offers sellers faster and privileged service from seller central for $20,000 per year.

| “In this unruly reality that Amazon created and fostered, even a tech giant like Apple could not effectively control the prices and distribution of their products.” |

The Recoupment Stage

If the primary purpose of the predation stage was to ensure the availability of almost any product at a competitive price on the Amazon platform, it appears that afterward, Amazon focused on recouping the losses it sustained. When the majority of the reluctant brands were finally beaten to submission and agreed to deal with Amazon directly or authorize its sellers to sell through the platform, Amazon could gradually purge the vendors that enabled it to establish its dominant position in the marketplace in the first place.

Amazon’s supplier purge seems to indicate a new potential problem for the company. Unlike Amazon, third-party sellers—both authorized and unauthorized— are unwilling or simply cannot afford to sell at a loss. This limitation made it harder for Amazon to ensure low prices on the platform. It had to make sure that products will not be offered at a higher price on Amazon in comparison to other outlets—even if such prices accurately reflect the ever-increasing costs associated with the fulfillment of Prime orders.

To remedy this, Amazon once again exploited brands’ MAP policies. As mentioned, MAP policies effectively dictate the minimum advertised price of a given product across the entire retail industry. Traditionally, this meant that the price of a typical product in a brick and mortar store would be lower than the price online, where consumers are charged an additional shipping fee at checkout.

Amazon, however, forced sellers to offer their products at the same price as brick and mortar stores. It also decided to bundle the costs of Prime fulfillment into the advertised price of products on the platform, which meant that sellers had to shoulder the hefty costs of Prime fulfillment alone. Amazon required sellers to match prices in other online outlets that did not incorporate fulfillment into their advertised prices, then told them it will “suppress” the “buy box” (or the Buy Now button) until they were able to match those lower prices. In simple terms, this meant that sellers lost the noticeable “buy now” button that makes shopping on Amazon so intuitive. Without the “buy now” button, consumers could still buy the seller’s goods, but they will have to engage in a much more convoluted process to find the buried items, which of course depresses sales.

These decisions placed third-party sellers between a rock and a hard place. If the sellers could not convince brands to raise their MAP, their Amazon business was destined to fail. They also transformed MAPs from a weapon that brands could use to combat Amazon to a tool that Amazon is now exploiting against the brands.

Nowadays, a brand will reach out to its authorized sellers on Amazon and tell them that it decided to implement a MAP for a given product. The sellers would then typically respond that they will be unable to break even at that given price, due to the high fees associated with fulfillment on Amazon and the fact that in order to “win” the Buy Box, the advertised price on the platform must be as low as the lowest price available in other outlets. The brand will then “republish” a higher MAP, effectively raising the price to a level that will allow the Amazon sellers to turn a profit. Since MAP policies are implemented almost across the entire retail industry (Walmart is a notable exception), the lowest asking price of the given product in any and all outlets will reflect the cost of Amazon fulfillment.

This intricate negotiation between brands and sellers results in higher prices for products, all in order to accommodate the need of third-party sellers to pay the ever-increasing fees involved in selling through Amazon. In addition, Amazon now actively intervenes in its marketplace in order to ensure that MAP policies are strictly enforced by the brands and that other outlets that do not adhere to MAP, such as Walmart, maintain price parity with Amazon.

One third-party seller, who asked to remain anonymous, was willing to turn over his books for inspection in order to illustrate the magnitude of the increase in consumer prices. Together, we analyzed a single product, of which tens of thousands of units have been sold since 2015. The minimum advertised price for this single product, at any and all outlets, has increased more than 30 percent in the past four years. Despite this fact, this seller’s margins on this product are tighter than ever due to Amazon’s fee increases.

Amazon’s primary tool of enforcement to ensure third-party sellers maintain price parity with other outlets is to suppress the Buy Box of a brand’s seller if it finds that the given product is sold at a lower price somewhere else. Their increased dependency on Amazon forced brands to raise MAPs and enforce these policies vigorously. In doing so, brands become increasingly dependent on Amazon and effectively lose their ability to control their products.

| “I believe that even a slight revision in Amazon’s policies might have a positive, tangible, and immediate impact on the dying retail industry.” |

Is There a Way to Counter Amazon’s Monoposnistic Dominance?

Amazon’s monopsonistic dominance over brands as the retail industry’s preeminent platform is harming consumers. Due to the price-matching policies Amazon set to ensure its dominant position, consumers are paying higher prices for products. Sadly, Amazon’s pricing policies are especially damaging to the poorest consumers, those who cannot afford a Prime account or don’t have a permanent address. These consumers are now paying higher prices at the dollar store or at CVS because brands have to ensure that their Amazon business is profitable.

Amazon’s conduct also harms non-Prime members who shop online, since they are unable to find the products they are buying at a lower price—even if the outlets where they shop could offer those products at a lower price.

By bundling the fees of fulfillment and shipping into the product’s total price, Amazon is effectively depriving its own customers the ability to choose between the speed of fulfillment and the price of the product. Amazon customers could potentially save hundreds of dollars a year, for instance, by choosing to ship less urgent items in a slower manner. While Amazon does already offer this option, consumers are not adequately compensated for selecting the slower shipping option.

There are various proposals on how to remedy the harm caused by Amazon, many of them thought-provoking and worthy. However, after studying Amazon’s conduct and business model rather closely, I believe that even a slight revision in Amazon’s policies might have a positive, tangible, and immediate impact on the dying retail industry and will, of course, benefit consumers.

First, Amazon should unbundle fulfillments fees from the total price of products. This means that Amazon customers will be billed separately for fulfillment at checkout, based on the speed of delivery they opt for and the fulfillment costs associated with the products they ordered, similar to the way in which taxes are currently added at the checkout screen.

Second, Amazon should remove unauthorized third-party sellers and force all sellers to reveal their corporate identity. It should disclose the actual corporate identity of all its suppliers and disclose to consumers the supplier of the given item they bought.

Lastly, Amazon’s ability to set prices in the marketplace should be curtailed. It should be prohibited from engaging in Buy Box suppression.

If Amazon refuses to adopt these changes, legislators and regulators should step in and ensure that they are implemented. Once these measures are implemented, brands will be able to immediately lower MAPs across the board. Both brick and mortar stores and online sellers will be able to compete with Amazon on price and perhaps in time develop cheaper and quicker fulfillment methods than Prime (although this is unthinkable right now). This simple solution might diminish Amazon’s current stranglehold over the market and would give regulators, legislators, and competitors some time to carefully articulate a fair, competitive and equitable vision of retail in the 21st century.

[Note: Amazon did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.]