Online degrees are reshaping higher education by lowering tuition prices and reducing in-person program availability. In new research, Nano Barahona, Cauê Dobbin, and Sebastián Otero find that Brazil’s high online enrollment benefits those who need cheaper and more flexible options, but ultimately hurts young undergraduate students who are shifting away from higher-value in-person education options.

Over the past decade, online college degrees have expanded rapidly. Once a niche option, fully remote undergraduate programs are now an important feature of higher education systems around the world. By 2019, fully remote enrollment shares were approximately 44% in Brazil, 17% in Mexico, 15% in the United States, 14% in India, 13% in Australia, and 8% in the United Kingdom. This growth has been driven by advances in digital technology, regulatory changes, and rising demand from students seeking more flexible and affordable ways to earn a degree.

The expansion of online education has generated mixed reactions. Supporters emphasize its potential to broaden access to education, particularly for students who face geographic, financial, or time constraints. Critics worry about educational quality, post-graduate outcomes, and the long-term implications for traditional colleges. Much of this debate treats online education as a simple trade-off between access and quality. What is often missing is a broader view of how online degrees reshape competition among institutions, and how those competitive effects, in turn, affect students.

Higher education is not just a collection of independent programs. It is a market in which institutions compete by encouraging and maintaining student enrollment, setting tuition prices, and deciding which degrees to offer. Changes on one side of the market—such as the entry of lower-cost online programs—can have consequences for prices, enrollment patterns, and program offerings.

These competitive dynamics matter because in-person college programs are significantly more costly to operate. Campuses require physical infrastructure and human resources, including the presence of faculty and staff. When enrollment falls, institutions may not simply shrink; they may close programs or exit markets altogether. As a result, even policies or technologies that initially benefit students through lower prices can ultimately reduce the set of options available, especially higher-quality, in-person ones.

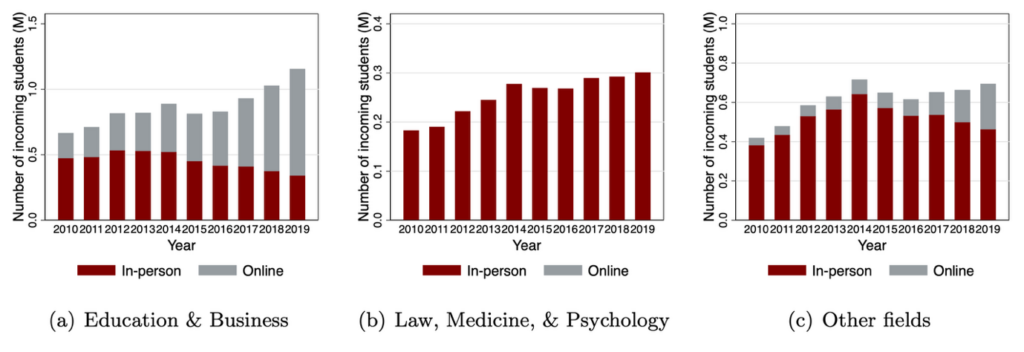

To understand these dynamics, we study the expansion of online higher education in Brazil, the largest market for online undergraduate degrees in the world. Brazil offers a useful setting because online programs grew rapidly over a short period, accounting for 17% of all new undergraduate enrollments in 2010 and 44% by 2019. Online programs must include in-person sessions for essential activities such as assessments and laboratory work, which must be conducted either at the institution’s main campus or at designated local hubs. Moreover, some fields of study face restrictions on being offered online (e.g., Law, Medicine, and Psychology). Finally, government reforms introduced in 2016 have streamlined the accreditation process for new online programs and granted institutions greater autonomy to establish new hubs. These regulatory rules created substantial variation in where and in which fields online degrees could expand, allowing us to study how local markets responded to the entry of online programs.

Figure 1: Expansion of online education by field of study

The first step is to compare online and in-person degree programs directly. While fields like law, medicine, and psychology more often require in-person learning, other areas, like education and business, have seen increases in online enrollment. Focusing on equivalent programs offered by the same institutions, online degrees are dramatically cheaper: tuition is roughly 40% lower.

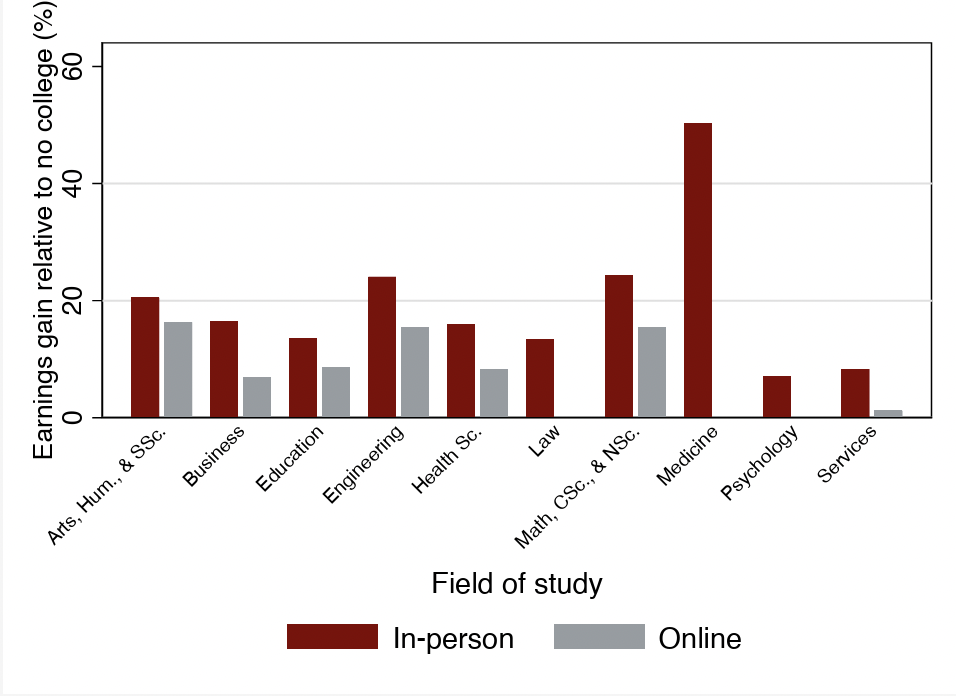

Completion requirements are similar between online and in-person programs, and dropout rates are slightly lower in online programs, likely due to greater flexibility and lower prices. Yet when students’ labor market outcomes are tracked over time, online degrees generate substantially lower returns. On average, enrolling in an online program raises earnings relative to not attending college, but by much less than enrolling in an in-person program. For example, in the business field, those with an in-person degree earn around 18% more than someone with no degree, while those with an online degree earn only about 8% more. This gap is especially large for younger students early in their careers.

Figure 2: Labor-market returns for in-person and online degree programs

To understand how online education affects markets, we assess variation in the local entry of online degrees across regions and fields of study. When online programs expand in a local market and field of study by 1550%, total college enrollment rises by 14%. Half of the students who enroll online would not have attended college otherwise.

But this is only half the story. Roughly half of online students are diverted from in-person programs they would have otherwise attended. This diversion is not innocuous. It moves students from higher-return in-person degrees into lower-return online alternatives.

At the same time, increased competition from online programs puts pressure on traditional institutions. In-person programs face high fixed costs from maintaining and improving campus facilities and resources. In regions and fields with greater online expansion, like Education and Business, tuition for in-person degrees falls and some programs become unprofitable, causing in-person programs to be reduced or cut entirely.

Once a program closes, students who prefer in-person education may have no nearby alternatives. Some switch to online programs; others leave higher education altogether. In this way, initial price competition can evolve into a reduction in choice, particularly for students who value face-to-face instruction.

The consequences of online expansion are not evenly distributed. Older students aged 26-45—who are less likely to attend college in the first place and place a high value on flexibility—benefit substantially from online options. For them, online education increases access and improves outcomes.

Younger students face a different trade-off. They are more likely to attend college regardless, and they financially benefit more from in-person instruction. When online programs expand and in-person options shrink, younger students are more likely to be diverted into lower-return degrees.

These findings suggest that the policy challenge is not whether online education should exist. Online degrees clearly provide value for many students. The challenge is how to integrate them into higher education systems without unintentionally crowding out higher-quality options.

One implication is that policies governing online education should be sensitive to who benefits most. In our analysis, alternative policies that disincentivize younger students from enrolling in online degrees, such as adjusting online fellowship and grant opportunities, increasing overall value added while preserving gains for those who rely most on flexibility. The goal is not to limit access, but to target it more effectively.

The expansion of online education illustrates a broader lesson about market design. Introducing cheaper, lower-quality options can expand choice in the short run, but also reshape competition in ways that reduce quality and variety over time. These dynamics are especially important in markets like education where quality is hard to observe and institutions face high fixed costs.

As policymakers continue to promote digital solutions across sectors, understanding these equilibrium effects will be essential. Access matters, but so does the structure of the markets that provide it.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.