In new research, Dragan Filimonovic, Christian Rutzer, and Conny Wunsch find that generative artificial intelligence not only enhances the productivity of scientific researchers, but also lowers barriers to entry for early-career scholars and scholars who are not fluent in English. Rather than attempting to prohibit GenAI’s use, institutions should develop disclosure guidelines to facilitate trust and support adoption.

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is reshaping academia. Its impact on science has become particularly visible since the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, as scientists around the world have started to integrate GenAI into their daily work. Our study of social and behavioral scientists shows that those who use these tools publish substantially more papers without any decline in quality. This is particularly evident among early-career scholars and scholars in technically oriented subfields. In addition, by lowering barriers to entry that have long favored native English speakers and elite institutions, GenAI is starting to rebalance the global market for scientific ideas. Researchers based outside English-speaking countries are the third cohort that have benefited the most from GenAI. Together, these results suggest that GenAI is reducing structural barriers in academic publishing and that the research community needs to rethink editorial, access, and disclosure policies to keep pace with its rapid diffusion.

How we measured GenAI adoption

To uncover how GenAI is changing academic productivity, we tracked individual researchers in economics, sociology, and psychology from 2021 to 2024 using data from one of the largest publication databases, Scopus. To identify GenAI adopters, we analyzed linguistic patterns in papers’ abstracts and titles. Specifically, we flagged researchers whose writing incorporates terms that spiked abnormally in frequency after 2022, when ChatGPT launched, and thus indicate the use of GenAI. These include terms such as “delve,” “meticulous,” and “unveil.” We restricted the keyword list to terms whose frequency rose by at least 200% between 2022 and 2024 to reduce false positives from normal topical or stylistic drift. To address the possibility that early adopters were already more productive (selection bias), we compared them to a control group. For each adopter, we identified one or more non-adopters with almost identical characteristics in 2021, such as publication record, field, and career stage. Hence, we tested for the difference in the number of published papers between comparable researchers.

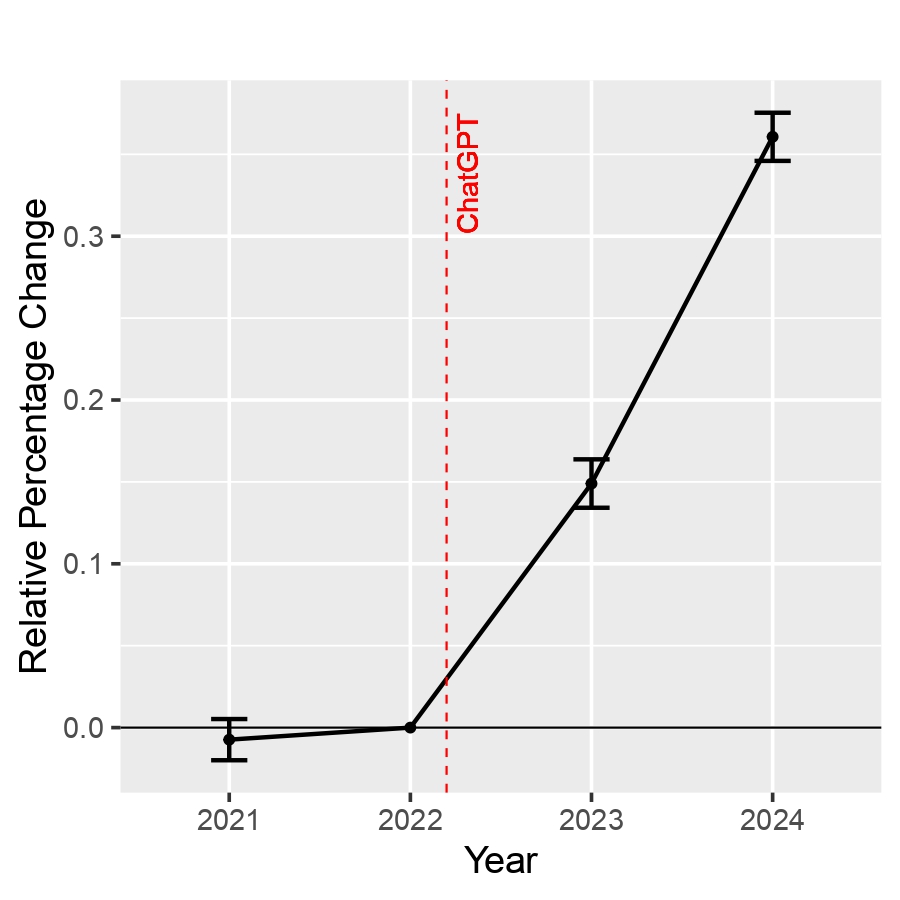

Our data show clear evidence of GenAI’s benefits for scientific publishing. Compared with similar non-adopters, researchers who used GenAI increased their publication output by about 15 percent in 2023, and as they became more familiar with the new tool, that number rose to 36 percent in 2024. To investigate whether this came at the expense of quality, we examined where adopters published. We kept journal impact factors fixed at their 2019 levels to ensure that shifts in rankings did not affect the results. GenAI adopters published after the release of ChatGPT in journals with slightly higher impact factors: about 1.3 percent higher in 2023 and 2.0 percent higher in 2024. Overall, researchers who adopted GenAI produced more papers and published them in slightly higher-quality journals than comparable non-adopters, compared to the period before ChatGPT’s release. This pattern indicates substantial productivity gains among adopters without any evidence of a quality penalty.

Because early adopters might differ systematically from other researchers, we tested whether our findings were sensitive to alternative definitions of adopters and comparison groups. Such design choices could, in principle, affect our estimates by shifting the balance between false positives and false negatives in identifying adopters. Specifically, we varied the matching design (using alternative adopter vs. non-adopter matching ratios), tightened or relaxed the keyword selection filter, and applied stricter percentile-based definitions of GenAI adopters. The results remained consistent, suggesting that any misclassification is limited. At the same time, our approach likely understates GenAI adoption, since the use of AI for coding, literature searches, or revisions often leaves few linguistic traces. The true effects are therefore probably even stronger than what we observe.

Figure 1: Effect of GenAI use on Scientific Productivity (left) and Quality (right)

Who gains most

The distribution of benefits from GenAI is not uniform. Effects are larger in more technical subfields such as economics and psychology compared to sociology, among early career researchers, and for authors in non-English-speaking countries. We find similar gains for men and women.

At its core, academic publishing is a market with high fixed costs: a lot of time is required to review the literature, gather and clean data, conduct analyses, and write and edit the paper. Research often requires specialized skills, such as econometrics, and language fluency, especially in English, in which many academic journals publish. GenAI mitigates these costs. You do not need a large laboratory budget to use GenAI, and unlike many other research tools, it is easily accessible from almost anywhere in the world (unless governments ban it). In our data, the largest productivity gains appear where frictions are steepest—thin support networks (e.g., mentorship or grants), complex methodologies, and editing or translation burdens—indicating that the technology delivers the greatest returns where traditional bottlenecks are highest.

This contrast becomes clearer when viewed from a historical perspective. For decades, access to research capital has been concentrated and scarce. It required affiliation with an elite and well-funded university, access to senior scholars for mentorship, or large grants. Such capital created high barriers to entry and reinforced existing hierarchies. That is precisely what GenAI is beginning to change, as it represents a fundamentally different form of capital for knowledge production: democratized, currently inexpensive, and available to nearly anyone with an internet connection.

This shift from concentrated to distributed capital is a classic disruptive force, and our data show that it is already making a pronounced impact. Consider the language barrier. GenAI acts as a universal polisher, reducing the stylistic and idiomatic disadvantages that have little to do with the quality of an idea but determine how it is received. This allows researchers in Seoul or Berlin to write with the fluency of a native English speaker in Cambridge (the United Kingdom or Massachusetts). In addition, for early-career researchers, GenAI serves as a digital co-pilot, helping to structure arguments, refine methods, and brainstorm counterarguments.

GenAI disclosure vs. prohibition

GenAI is not an unalloyed benefit to academia. Broader concerns about GenAI chatbots hallucinating facts and making errors in data manipulation are well-documented. Although we found that scholars have been able to use GenAI to improve the quality of their work, as measured by which journals accept their work, there are concerns that this may be because journal referees are not yet aware of all the ways in which GenAI can compromise scholarship. There are also present ideas of fairness and integrity, and some believe that GenAI degrades scholarship in the same way that artists argue GenAI degrades art. So, an important question arises from our findings: If GenAI adoption is rising and the gains are real, how do we maintain trust in future scientific outputs?

One suggestion is for academic journals and publishers to ban or restrict the use of GenAI in what they publish. This will effectively disincentivize scholars from using GenAI or to use it only where permitted, such as for literature reviews. However, efforts to enforce prohibition are not only ineffective; they are poor market design. When a useful technology is banned, it does not disappear. It simply goes underground. This creates a shadow market where those who use the tool to generate entire texts or produce misleading content could become indistinguishable from honest researchers who use it for linguistic support, as neither group can disclose their usage. This ambiguity about who uses the tool and for what purpose ultimately erodes trust. A blanket ban punishes the very groups that our data show GenAI benefits most, while doing little to prevent genuine misconduct.

Many institutions rely on AI detectors to enforce prohibition. Evidence suggests that these systems are brittle, easy to bypass, and often flag non-native writing as “AI-generated.” Our results show that the largest benefits occur precisely where linguistic frictions are highest, further reducing the viability of detectors as an enforcement tool.

Instead, clear authorship and disclosure guidance, combined with strong peer review processes, offer a more effective path than technological gatekeeping that mistakes lack of fluency for deceit. We advocate for a transparent disclosure model based on simple, standardized statements at the article level that indicate whether and how GenAI tools were used (e.g., for language polishing, coding assistance, or drafting). Ideally this would appear in a dedicated disclosure field alongside existing data or conflict-of-interest declarations. Such transparency enables the community to establish new norms, as it did with the introduction of statistical software and more recently with data sharing and pre-registration of research trials and experiments. If adoption is disclosed clearly, the market for scientific ideas can reprice what it values. Textual polish may matter less, and genuine novelty, solid data, and creative insight may matter more. That is a far healthier outcome than prohibition. Instead of resisting the tide, clear guidelines allow institutions to adapt, ensuring that this new form of capital strengthens trust rather than sowing suspicion.

Looking ahead

The early signal is hard to ignore. When new technology removes old barriers, it does not merely speed up the same researchers doing the same work. It changes who can participate. Our results show that GenAI is already flattening steep gradients in academic writing linked to career stage, field technicality, and language. If institutions meet this shift with openness and transparency, the payoff will not only be more papers but a research system that is faster, fairer, and more open to talent wherever it exists.

There is still a long road ahead in measuring adoption and evaluating GenAI’s broader impact on academic publishing. Our analysis focuses on the social and behavioral sciences. Other fields, especially STEM, may evolve differently. Our text-based proxy captures adoption for writing, but not how researchers use GenAI across the full research process, from planning to coding and analyzing to writing. In the short term, we see more papers and slightly higher quality. In the long term, editors and reviewers may raise expectations, novelty could be repriced, and attention might shift. These dynamics warrant continued observation and debate as GenAI reshapes how science is done.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.