In the first of two articles, Jeff Alvares explores how Brazil’s public digital payments system achieved transformative financial inclusion through vertically integrated infrastructure, creating a model now facing scrutiny under international trade law and raising questions about the boundaries of legitimate public infrastructure provision.

In July, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) initiated a Section 301 investigation into Brazil’s public instant-payment system, Pix, for discriminatory practices that harm U.S. commerce. Coming weeks after the USTR had flagged India’s and Indonesia’s public payment services in its Foreign Trade Barriers report, the move signals a new front in global trade tensions centered on industrial policy, financial regulation, and antitrust in the digital economy.

At stake is a fundamental question: to what extent can governments deploy regulatory power and public digital infrastructure to achieve social goals like financial inclusion—the stated purpose of Pix—when doing so reshapes competitive dynamics? The outcome will set a precedent for which services central banks can provide on an exclusive basis, prompting a reassessment of international trade rules poorly adapted to state-led digital platforms.

The architecture and economics of payment systems

Payment systems traditionally separate infrastructure from user-facing services. Central banks provide wholesale settlement “rails” that move money from one bank to another—such as the Federal Reserve’s Fedwire or Brazil’s Reserve Transfer System (STR)—while private payment schemes—Visa, Mastercard, American Express—compete on user experience and features. Banks operate intermediary systems that clear retail transactions between payment-scheme participants—such as the Automated Clearing House (ACH) in the U.S. and the Funds Transfer System (Sitraf) in Brazil,—settling their net positions through their accounts at the central bank.

Unlike traditional markets, payment systems exhibit unique economics. Network effects mean a payment method accepted everywhere becomes indispensable, creating powerful incumbency advantages. Two-sided market dynamics require coordinating merchants and consumers simultaneously, favoring platforms with existing relationships with both. Payment infrastructure involves massive fixed costs but minimal marginal costs, creating natural monopoly conditions.

These features explain why payment markets gravitate toward concentration. They also reveal why traditional antitrust analysis, built on assumptions that more rivalry always improves outcomes, may be inadequate for digital-infrastructure markets, where concentration can enhance efficiency.

Changing payments landscape

Before the internet, payment systems faced restricted access, high costs, and slow settlement. All of this was particularly true in emerging markets. Limited banking competition constrained access to payment services, increased fees, and reduced incentives to adopt faster technologies.

With the internet came non-bank payment-service providers (PSPs) that expanded access to transaction accounts beyond banks. Then emerged instant-payment systems (IPSs), both public and private, powered by settlement infrastructures that made funds available to payees in real-time on a continuous basis (24/7/365). These include FedNow and RTP in the U.S., BI-FAST in Indonesia, UPI in India, and SIC in Switzerland. Various payment schemes operate atop these rails such as Zelle (U.S.), QRIS (Indonesia), Google Pay, Paytm and PhonePe (India), and Twint (Switzerland).

IPSs vary significantly across countries in how they permit competition on their infrastructure and application levels. Competitive-market models like the U.S. FedNow or European Union’s SEPA maintain both infrastructure and applications as substantially competitive. In the U.S., FedNow, which was developed by the Federal Reserve, competes with RTP, offered by The Clearing House. Instant-payment schemes have the choice of settling through their own networks or via any of the back-end systems available. Zelle, for instance, settles via ACH if the sender’s or receiver’s bank is not on the RTP network, and it could potentially connect to FedNow at any time.

Infrastructure-layer monopolies like India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) provide exclusive public settlement infrastructure while leaving applications open to private competition. In turn, vertically integrated monopolies like Brazil’s Pix involve exclusive government operation of both infrastructure and application layers, with mandatory participation and zero pricing.

Developed countries tend to favor private sector competition to prevent digital monopolies from entrenching through network effects. Developing countries lean towards more interventionism to achieve universal access when private markets won’t serve low-income populations profitably.

This distinction is central for international trade law: competitive models face minimal scrutiny; infrastructure monopolies may fall under governmental-authority exceptions; and vertically integrated monopolies face the greatest exposure for hindering competitive opportunities.

The Pix story: From market failure to radical intervention

Brazil’s payments landscape before Pix launched in 2020 exemplified market frictions. A few major banks dominated both infrastructure and customer-facing applications. Wire transfers cost $1.50-3.00 USD and took hours or days to clear. Credit card fees reached 2.2% on average, compared to 1.7% in the U.S., 1.5% in Canada, and 0.3% in the European Union. Around 45 million Brazilians, about 29% of the population, remained unbanked and excluded from digital commerce. Existing players had little motivation to incur the fixed costs of infrastructure that could cannibalize their card fees and transfer charges. Incumbent banks and card networks benefited from fragmented, costly rails.

The Central Bank conceived Pix to overcome this structural inertia. It now operates the Instant Payment System (SPI) infrastructure to provide real-time settlement around the clock. Use of this rail is mandatory for banks and major PSPs. Pix itself, the payment scheme running atop the SPI, is also Central Bank-controlled, with mandatory participation, and zero pricing for services to individuals and small businesses. (In common parlance, Pix refers to both the payment scheme and the vertically-integrated payment system including SPI).

The cornerstone of Pix’s integrated design is a combination of legal and economic barriers to potential competing payment schemes.

Legally, the SPI was built exclusively for Pix, and other payment schemes cannot connect to it for instant settlement. Any alternative front-end service would need either to build its own instant-settlement rails—an implausibly costly undertaking—or to rely on slower legacy systems such as the Central Bank’s STR or the bank-run Sitraf—much as Zelle uses ACH for transactions outside the RTP network. However, settlement through these channels wouldn’t be instant, fundamentally limiting any competing scheme’s ability to match Pix’s core value proposition.

Economic barriers compound the foreclosure. Even if a competing scheme could somehow access instant-settlement infrastructure, Pix’s mandatory participation requirements mean all major financial and payment institutions must offer it. Combined with zero pricing for users, this creates insurmountable competitive disadvantages: a rival scheme would need to convince banks and nonbank PSPs to support a second instant-payment system while charging fees that Pix does not, and would face a market where Pix already reaches the vast majority of consumers and merchants. The network effects that made Pix successful have also dug a powerful economic moat around it.

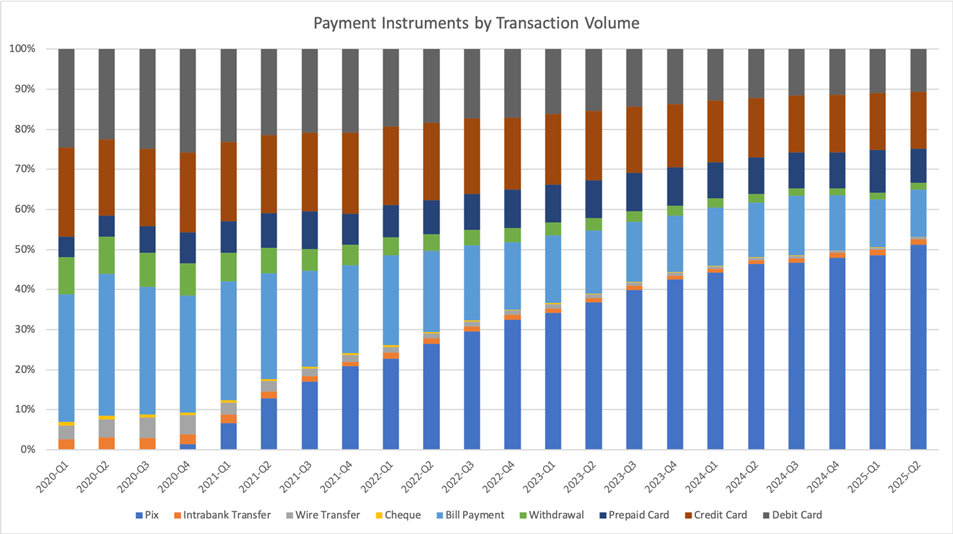

Pix’s fast, affordable, and near-universal model has achieved transformative results. It now reaches 177 million users (83% of population) and accounts for 51% of all payment methods, displacing payment cards and bank instruments alike (see chart). It processes seven billion monthly transactions worth $550 billion. For millions, it became the gateway to the digital economy.

Despite stifling competition in parts of the market for instant-payment services, the SPI-Pix integrated model has had apositive impact on competition elsewhere in the financial sector. Its competitive neutrality has spurred the growth of PSPs that vie for deposits with banks and provide better and cheaper products and services. Despite reducing incumbents’ market share, there’s evidence that Pix correlates with the use of other payment methods and banking products.

Still, the lack of competition on the front end of instant payments might restrict innovation in technological features such as security solutions and complementary product offerings such as embedded lending, investment or insurance, rewards programs, cash management tools, and cross-border networks. The very design features enabling financial inclusion success could create obstacles to service differentiation that typically drives competitive application markets.

Therefore, while Pix has promoted competition among banks and nonbanks in the broader provision of financial services—transaction accounts, lending, and other products—it may have stifled the development of competition in the market for instant-payment services more narrowly. The result is a system with unprecedented inclusion but limited rivalry at the scheme level.

Pix delivers transformative social benefits, but it does so through foreclosure rather than through competition among payment schemes. This tradeoff raises profound questions for antitrust policy and international trade law. In part II, I will discuss the complex legal arguments on both sides.

Author Disclosure: Jeff Alvares is senior counsel at the Central Bank of Brazil. The views expressed are his own and do not represent those of the Central Bank of Brazil or the Brazilian government.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.