Rebecca Haw Allensworth writes that the hallmark of the new conservative antitrust is not economic populism but silencing speech that the Trump administration ideologically opposes.

This article is part of a symposium that explores the meaning and future of a conservative antitrust based on the writings and policies of the antitrust enforcers in the second Trump administration. You can read the contributions from Rebecca Haw Allensworth, Thomas Lambert, Gus Hurwitz, Christopher Sagers, and Aviv Nevo as they are published here.

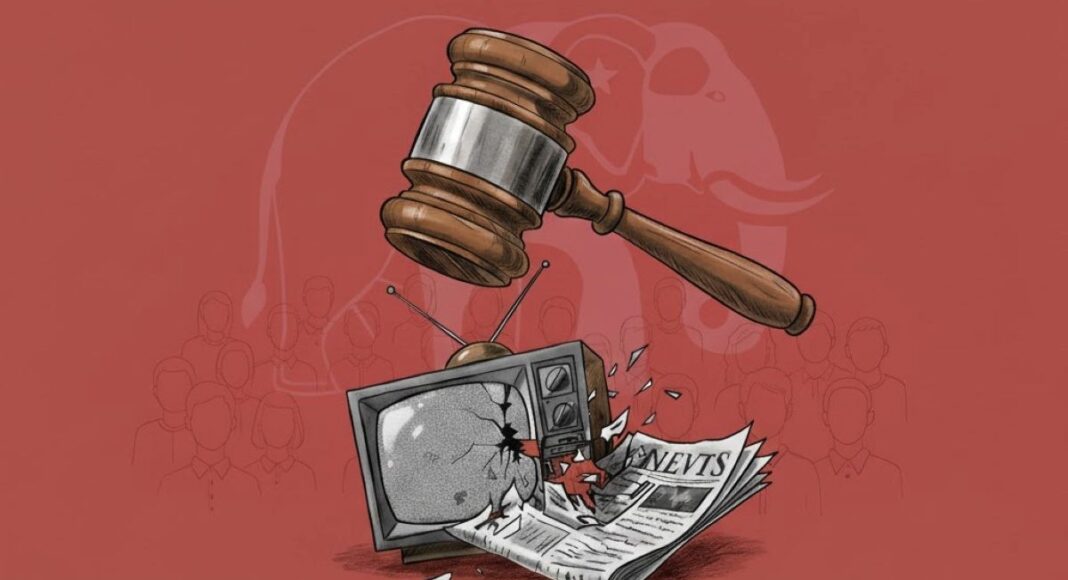

“Conservative,” as a term for antitrust under Republican administrations, has taken on a new meaning under President Donald Trump. For decades, “conservative” antitrust was laissez faire. Then, as the Republican platform evolved away from free-market and pro-business policies during the first Trump administration, “conservative” antitrust seemed to align with populist goals like confronting inequality and consolidated economic power. Today, while the second Trump administration uses populist rhetoric to describe its competition policy, its actual decisions in key merger cases reveal a different set of commitments. In these cases, Trump’s “conservative” antitrust is, in practice, neither laissez faire nor populist. In reality, it isn’t antitrust at all—it’s anti-speech.

“Conservative” has always been a slippery word. Yet in antitrust, at least until recently, that word has had a relatively stable meaning. Since the late 1970s, “conservative antitrust” meant minimalist enforcement and narrowing the paths to holding businesses liable for anticompetitive activity. This shift away from antitrust intervention was championed by Robert Bork, who made no secret of his right-wing political views. It was carried out, in no small part, by antitrust agency heads appointed by the great Republican hero, President Ronald Reagan. Laissez faire antitrust fit with the Republican brand of conservatism that championed free markets, limited governmental intervention, and technocratic economic policy that sought to, in the words of another conservative president, “make the pie higher.”

We all know that Reagan’s conservatism and Republican party are gone. At least as a rhetorical matter, populism has replaced libertarian economic policy. Take, for example, Trump’s policy on tariffs, which he says makes him “the first President in modern history to stand strong for hardworking Americans.” But if populism were the animating principle behind Trump’s antitrust agenda, then his merger policy might look a lot like that under the Biden administration. We might expect Trump’s agencies to use aggressive merger enforcement to slow the growth of large corporations that, according to the populist narrative, consolidate a dangerous degree of economic power in a few mega corporations. Indeed, several prominent Republicans threw their support behind the efforts of the Biden antitrust enforcers: economic populism makes for strange bedfellows.

But economic populism does not seem to guide the second Trump administration’s merger enforcement, nor do these recent moves signal a return to old-school conservatism in the form of laissez faire. Instead, Trump is using antitrust to silence dissenting voices and distort the information available to the public in ways that benefit him and his party politically—goals that have never been legitimate aims of antitrust.

There were early signs of this shift in the first Trump administration. Some observers viewed his administration’s decision to challenge AT&T’s merger with Time Warner as political retribution for CNN’s coverage of Trump during his first presidential campaign. At the time, Time Warner owned CNN. These days, the data points are more numerous, and the anti-speech priorities are more naked.

Consider Trump’s efforts to fire the two Democrats on the Federal Trade Commission, a move that hasn’t been attempted since President Franklin Roosevelt tried it and was shot down by the 1935 Supreme Court ruling in Humphrey’s Executor. Trump’s firings assured that not only would Democrats have no votes on FTC decision-making, but that they wouldn’t even be able to issue dissents to provide official counterviews. Historically, published dissents by sitting commissioners have been an important part of the FTC’s process, promoting transparency and accountability.

The saga of Paramount’s acquisition of Skydance is another datapoint, even if it technically involves merger enforcement outside of antitrust. The Department of Justice, which usually handles media mergers when they present competitive problems, apparently declined to challenge the merger. The Federal Communication Commission, however, threatened to use its broader mandate—to block mergers when they are not “in the public interest”—to hold up the deal.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that the FCC relented after receiving promises from the merging parties that they would amplify conservative content. Indeed, the FCC’s approval euphemistically required that the merged company’s programming “embod[y] a diversity of viewpoints across the political and ideological spectrum.” Another piece of evidence of a quid pro quo between CBS (a subsidiary of Paramount) and the FCC is CBS’s sudden decision to cancel Stephen Colbert’s “The Late Show.” CBS announced the cancellation two days after a closed-door meeting between the head of the FCC and the CEO of Skydance and nine days before the FCC announced its approval for the merger. This seems to be retaliation, undertaken at the behest of the FCC, for Colbert’s on-air statements criticizing Trump and Paramount.

Perhaps the most egregious example, however, and one receiving far less attention than the Paramount-Skydance merger, is the FTC’s consent order approving the merger of Omnicom and Interpublic Group, two global advertising holding companies. According to a statement released by FTC Chairman Andrew Ferguson on the day the agency announced its conditional approval of the merger, the primary concern, from a competition perspective, was that the merger would facilitate collusion among advertising holding companies to boycott publishers of conservative viewpoints.

Despite these concerns, the FTC approved the merger, but on only on terms that were bad both for consumers and for free speech principles enshrined in the First Amendment.

First, consider the consumer welfare effects of the consent order. Ostensibly, the order preserves the right of the merged Omnicom firm to unilaterally offer services that would allow an advertiser—in this case the consumer—to avoid placing ads on media the advertiser finds offensive or harmful to its brand. Put more simply, the consent order technically permits Omnicom to discriminate among media publishers based on their viewpoint. Indeed, Ferguson claimed in his statement that “[n]o one will be forced to have their brand or their ads appear in venues and among content they do not wish.”

In reality, however, the consent order threatens consumers’ ability to choose which viewpoints to associate with their brand or product. The order makes unlawful any reliance on third-party “exclusion lists,” meaning that Omnicom will have to create bespoke lists of websites with unacceptable content for every client. It may not even recycle a list from one client’s project to another. This raises the cost of providing viewpoint-based services, services that even Ferguson admits are perfectly lawful to provide. By how much, and whether the order makes it prohibitively costly, is unknown, because Omnicom was evidently motivated enough to merge to not raise the issue.

Second, even setting aside the consumer welfare implications of the order, it far oversteps the proper bounds of antitrust laws. The evil at which the consent order is aimed—in Ferguson’s words, the “deliberate, coordinated efforts to steer ad revenue away from certain news organizations, media outlets, and social media networks”—is itself protected speech under the First Amendment and therefore out of bounds of the antitrust laws. It is perfectly legal to use economic power, even through an explicit agreement, to attempt to influence public discourse.

The Supreme Court held as much in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, an antitrust case challenging a 1960s group boycott, organized by Black activists, against white store owners who resisted integration. The Court affirmed that “boycotts to achieve political ends are not a violation of the Sherman Act.” The Court’s analysis turned on whether the aims of the boycott were “parochial economic interests,” such as increasing pay or revenue for the boycotters, or were “politically motivated” and “designed to force governmental and economic change.”

As if the FTC’s overstep were not clear enough, the consent order goes further, requiring that Omnicom retain, for the purposes of proving compliance with the consent order, all communications with clients about content-based advertising placement and a list of publishers that appear on any internal, bespoke exclusion lists. This information has no reasonable bearing on competition policy. It merely facilitates the Trump administration’s surveillance of viewpoint expression by private market actors, surveillence it has already begun of other media companies. Again, that Omnicom agreed to this surveillance and to relinquishing its First Amendment rights tells us nothing about consumer welfare or about the political freedom at stake. All it means is that it was more profitable for Omnicom to waive these important rights than to abandon the merger.

This order appears to be one of the ways the administration is operationalizing its stated intent to use antitrust against perceived liberal bias by tech platforms. One irony, if we try to understand this move as part of a “conservative” agenda, is the way that it abridges the rights of large companies to use their economic power to influence political discourse. This right, as vindicated in cases like Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, was once seen as an important plank in the Republican platform.

Readers will recognize that the policy changes the Trump administration is implementing are far from unique to antitrust. They echo Trump’s subjugation of higher education, where universities are giving up important speech rights and academic freedom in response to Trump’s threats to cut off federal funding. The Trump administration will continue to use the leverage that comes with federal power to strike “deals” with private parties that advance Trump’s ideological and political interests. For the targets of Trump’s antitrust enforcement, these bargains may be better than the alternative. But for consumers, speech rights, and the rule of law more generally, these deals spell disaster.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.