In a new NBER working paper, Charles Hodgson and Shilong Sun show that vertical integration is usually good for consumers, except when firms have both the ability and the incentive to foreclose rivals. They use the heavily integrated Chinese Film Industry to show that targeting enforcement to the markets where harm is predictable makes it possible to effectively regulate harmful cases and protect consumers.

The debate over vertical integration, wherein a company integrates multiple stages of production, such as product development and retail, is one of the most contentious topics in antitrust. While integration can create benefits by eliminating successive markups that compound at multiple stages of the supply chain, it also creates the risk of vertical foreclosure: where a firm uses its control of one layer of a supply chain to disadvantage rivals in another. This practice is a growing concern, seen everywhere from online marketplaces prioritizing their own products over those of competitors to brick-and-mortar retailers giving preferential shelf space to store-owned brands.

The key policy question is not whether vertical integration can ever be harmful, but the market conditions under which harm is likely to arise.

The “ability and incentive” framework in vertical merger enforcement

Competition authorities in the United States, European Union and Canada use an “ability-incentive” framework to assess the risk of foreclosure. A firm’s ability to foreclose rivals depends on its control over a bottleneck segment—typically a stage of the supply chain where rivals cannot easily go elsewhere. A firm’s incentive to foreclose rivals depends on how much it stands to gain from excluding upstream or downstream competitors, often driven by the closeness of competition.

This framework features prominently in major cases such as AT&T/Time Warner, Illumina/GRAIL, and Microsoft/Activision, where plaintiffs devoted substantial attention to whether the merged firm could meaningfully foreclose rivals.

Despite the centrality of this framework, existing findings on vertical foreclosure are, as many have noted, “decidedly mixed” about how it affects competition. Our research moves this literature forward by showing that these context-specific outcomes become predictable once viewed through the lens of upstream and downstream market structure—much in the same way regulatory agencies evaluate market structure in horizontal merger review.

A real-world laboratory: the Chinese film industry

We study the Chinese movie industry, a setting that provides clean data and a clear mechanism for potential foreclosure. Vertical integration is pervasive in the market: many theater chains own or are owned by film distributors. Downstream theater chains are the bottleneck; they control pricing and showtime allocation. If an integrated theater wants to favor its own films, it can screen them more frequently, pushing rival films to the margins.

The product line of film distribution in China is as follows: The State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT) grants distribution permits to a distributor for a film after censorship review. Once a permit is issued, SARFT centrally coordinates contracting between distributors and all theater chains. Two rules anchor the market: films are released nationwide on the release dates, and box-office revenue is split according to a fixed formula between the upstream producers/distributors and downstream exhibitors. This standardization means that differences in treatment across films shown in a theater are not driven by contractual differences. They reflect how vertical integration affects theaters’ choices for how much to charge audiences to see a film, which films they show in competition for audiences’ attention, or to show an individual film at all.

In our study, we analyze a dataset of ticket sales, prices, and showings for all nationwide-released films from 2011 to 2015. For each film, we also collect its star rating from China’s largest movie-rating platform to measure the similarities between distributed films. These data allow us to compare how film showings are allocated, rather than priced, to measure the difference between showings of integrated and non-integrated films.

Foreclosure exists, but only under specific conditions

We document three facts about foreclosure behaviors. First, foreclosure is real, measurable, and economically meaningful. On average, films shown in theaters that are not integrated with the film’s distributor receive around 4% fewer showings when competing head-to-head with a film that does come from an integrated distributor.

Second, foreclosure requires theaters to have enough market power to restrict competition. An integrated theater can only foreclose rivals if customers cannot easily switch to nearby theaters. When an integrated theater faces little to no spatial competition—i.e., operating as a local monopoly with no cinema within 5 km—the reduction in showings for rival films is strongest.

Third, foreclosure is most likely when films are close substitutes. In this case, distributors have the incentive to reduce audiences’ viewership of a competing film, assuming audiences are less likely to watch both. To measure the similarity between every pair of competing films, we use the machine learning algorithm applied in practical film recommendations on nearly two million consumer film rating records. Our results confirm that when a film from an unintegrated and rival distributor is very different from the integrated theater’s own title, incentives to foreclose rivals diminish sharply because they are not competing for the same audience. For example, if a theater’s own film is a niche art film, it has very little incentive to bury a Marvel blockbuster.

The policy punchline: targeted enforcement works

So, what does this mean for consumer welfare?

When we simulate the effects across all markets, efficiency gains for consumers from integration generally prevail because integrated theaters increase the number of showings for integrated films. But antitrust enforcement should focus on the exceptions. In fewer than 10 percent of markets, integration reduces consumer welfare, and those markets are predictable. In the film industry, they are the ones where distributor-integrated theaters have low downstream competition—giving them the ability to foreclose rival distributors—and where theater-integrated distributors face high upstream competitive pressure from rivals with close film substitutes—giving them the incentive to foreclose rivals. This pattern aligns closely with the logic embedded in the U.S. 2023 Merger Guidelines.

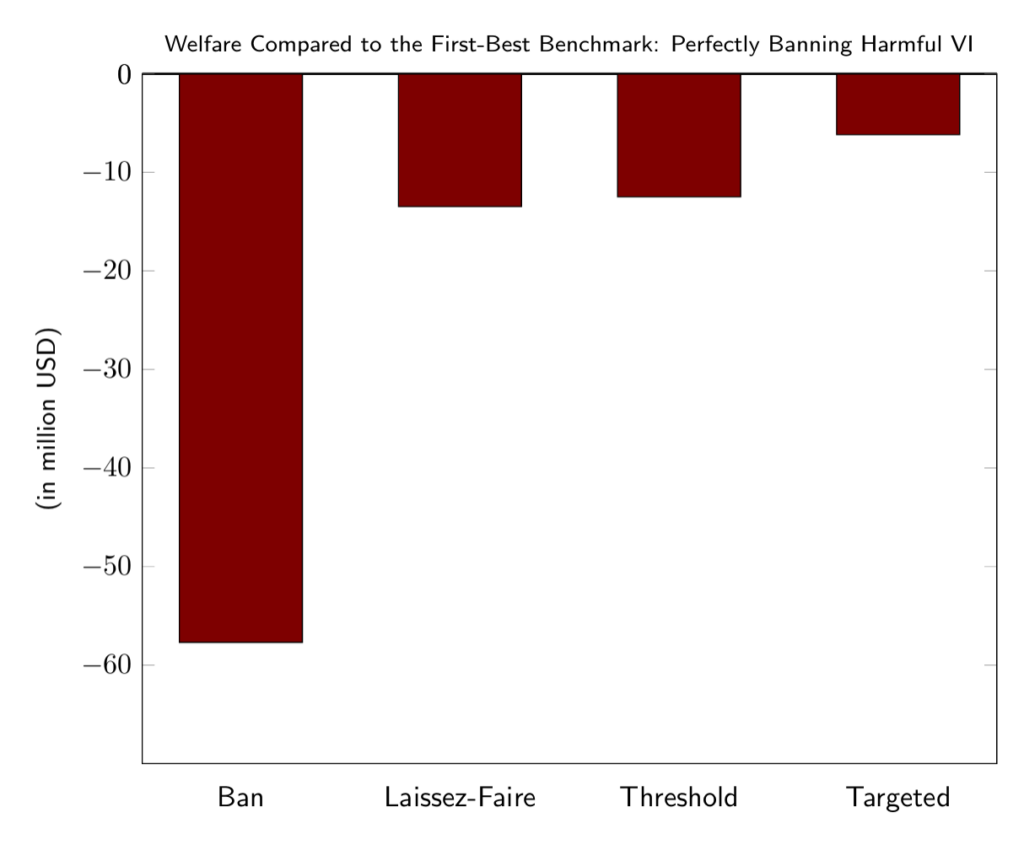

We then evaluate how consumer welfare changes under a range of policy designs. The results are presented in Figure 1.

1) A total ban on vertical integration: A blanket prohibition destroys substantial consumer surplus—millions of dollars in our simulations—because it eliminates the efficiency gains that occur in the vast majority of markets.

2) A laissez-faire policy: Doing nothing avoids the inefficiencies of a ban but ignores the predictable harms in foreclosure-prone markets. It results in over 20% of the welfare loss caused by the efficiency loss generated by a total ban.

3) A threshold-based policy: One simple alternative is to ban integration when theaters face too few nearby rivals or when films are too close in similarity. While easy to administer, this approach only achieves modest welfare gains.

4) A machine-learning-based targeted policy: A more precise approach uses a range of market characteristics, including local theater density and film similarity, to predict which integrations are likely to be harmful. This targeted rule is far more effective: it recovers nearly half of the welfare losses under the laissez-faire regime.

Figure 1: Consumer Welfare Impacts under Four Policy Scenarios

The policy lesson is straightforward. The debate should not be whether vertical integration is “good” or “bad,” but where it is likely to be harmful. Under the rule-of-reason standard that governs vertical cases, enforcers must demonstrate consumer harm—an analytically demanding and resource-intensive task. By grounding enforcement in horizontal market structure and identifying where firms have both the ability and the incentive to foreclose rivals, agencies can target the cases where harm is predictable. This allows them to develop screening tools and surgical remedies that protect consumers in uncompetitive markets without sacrificing the efficiency benefits that dominate elsewhere.

Author Disclosure: Charles Hodgson is an assistant professor at Yale University and a faculty research fellow at NBER. Shilong Sun is a Senior Economist at Compass Lexecon. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not purport to represent the views of Compass Lexecon. The authors report no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.