In new research, Seda Basihos investigates the relationship between a decline in market competition and global democratic backsliding. She finds that market concentration leads to increasing political power for giant firms—a trend that ultimately erodes democracy levels.

For decades, a fundamental tenet of political economy has been that competitive markets and democratic governance are mutually reinforcing. Competition disperses economic power, preventing any single entity from exerting undue influence over political decision-making. In turn, democracy provides the institutional foundations that allow competition to flourish.

But what happens when market competition declines?

My new research provides empirical evidence that the decline in market competition observed since the 1990s is a significant driver of the current trend in global democratic backsliding. Using data from 80 countries over three decades (1990-2019), I find that the concentration of market power in the hands of a few large firms leads to a concentration of political power, which in turn erodes democratic institutions. Counterfactual estimates suggest that roughly a quarter of the recent global decline in democracy can be attributed to the rise in corporate market power.

The twin trends: rising markups and falling democracy

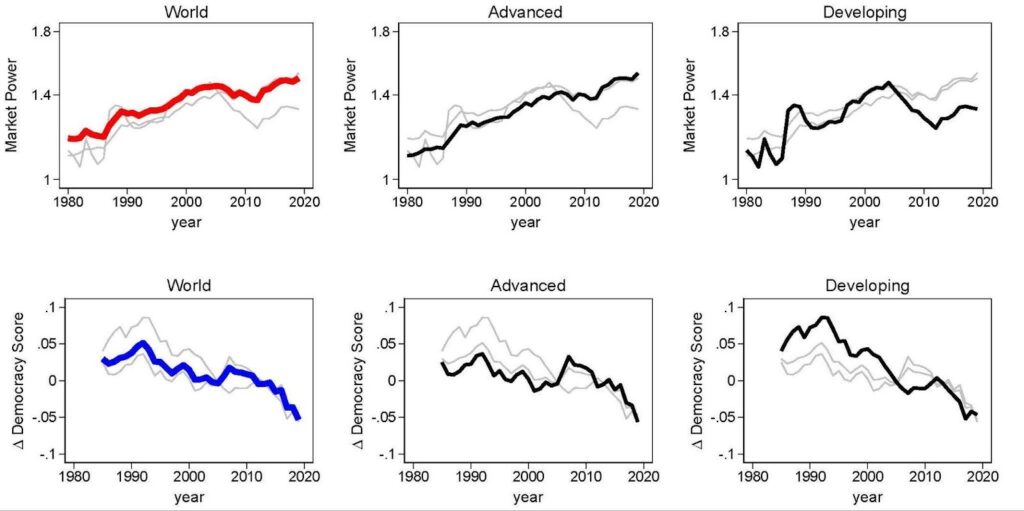

Two recent trends stand out in the global economic and political landscape. First, a growing body of research has documented a steady rise in corporate market power. Using financial data from over 57,000 publicly traded firms, I measure economy-wide market power through what economists call “aggregate markup”—the average amount by which firms’ prices exceed their production costs. This measure captures the concentration of market power across an economy. As Figure 1 shows, aggregate markups have increased significantly worldwide since the late 1980s, particularly in advanced economies.

Second, organizations like the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project have meticulously tracked a decline in democratic quality, as measured by factors such as the robustness of electoral and liberal freedoms. V-Dem’s Electoral Democracy Index shows that global democracy has been in retreat since the early 2000s, reversing nearly half the progress made since the end of World War II.

Crucially, the increase in market power preceded the measured democratic backsliding, raising a pressing question: Is this timing merely a coincidence, or are the two trends connected?

Figure 1: Evolution of Market Power and Democratic Backsliding Around the World

Establishing a causal link

Establishing causation is challenging. The relationship could run in both directions. Does market power undermine democracy, or do weakening democratic institutions allow powerful firms to emerge? While both are plausible, my research focuses on the first direction, as the rise in corporate market power clearly began before the democratic backsliding.

To disentangle this, I use a granular instrumental variable (GIV) approach. The identifying insight is straightforward: market power reflects both systematic factors (such as macroeconomic trends, technological changes, or even political conditions and regulatory choices) and random firm-level events. Because large corporations account for a disproportionate share of economic activity, unexpected shocks to these individual firms—such as operational disruptions, product innovations, or supply problems—create measurable changes in overall market power concentration.

These firm-level shocks serve as the instrument. They are unrelated to political conditions—as they are random—but directly affect aggregate market power. If market power genuinely undermines democracy, then random changes in market power should predict subsequent changes in democratic scores.

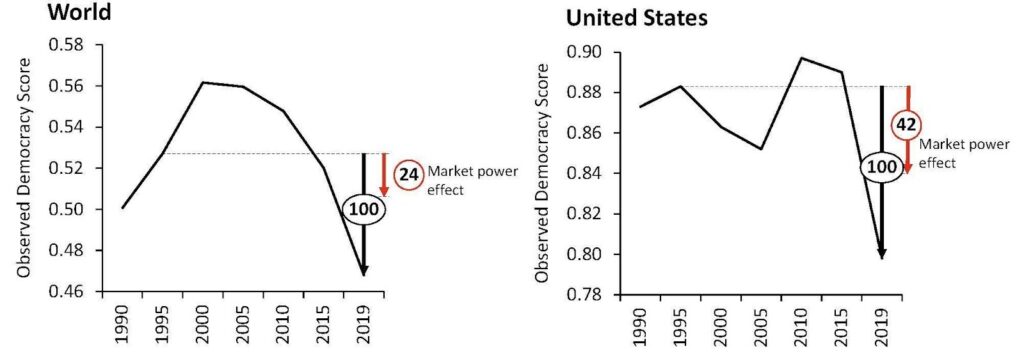

The empirical results strongly confirm this hypothesis. Random shocks that increase market power lead to statistically significant democratic erosion.The magnitude of this effect is not small. Figure 2 quantifies the contribution of rising market power to democratic decline through counterfactual analysis. The solid line shows the actual democratic trajectory from 1995 to 2019, while the dotted line marks the 1995 baseline level. The percentage indicates how much of the total observed democratic decline is attributable to increasing market power. In the United States, for instance, nearly 42% of the democratic erosion since 1995 can be attributed to growing corporate market power. Without this increase in market power, U.S. democracy would have declined far less—by 58% of the observed amount rather than 100%. Put differently, rising market power has pushed U.S. democratic quality back to levels last seen in the 1970s.

Figure 2: The Extent of Democratic Backsliding from Market Power.

It’s the biggest firms that matter

When I decompose the sources of rising aggregate markups, the largest firms—those in the top 5% by revenue—are almost entirely responsible for the total impact of economic concentration on democratic backsliding. A broad-based increase in markups across all firms has no discernible impact on democracy. It is the concentration of economic power at the very top that translates into political power.

Why? Because these very large firms have both the means and the motive to engage in politics. Their vast financial resources provide the capacity, and their dominant market position gives them the incentive to influence policy and regulation to protect their rents.

A firm-level analysis of U.S. lobbying data confirms this mechanism. Firms with higher markups spend more on lobbying, and this relationship is primarily mediated by firm size: higher markups lead to larger market shares and revenues, which in turn provide the resources for greater political engagement. For these corporate giants, lobbying expenditures represent only a tiny fraction of revenue—a small price to pay for maintaining political influence. Yet there are also other channels of influence that are not easily captured in available data.

How market power erodes democracy: the mechanisms

Large firms want to buy political influence, but is that all they are buying? My analysis tells us that their political influence comes at the cost of a corrosion of core democratic institutions.

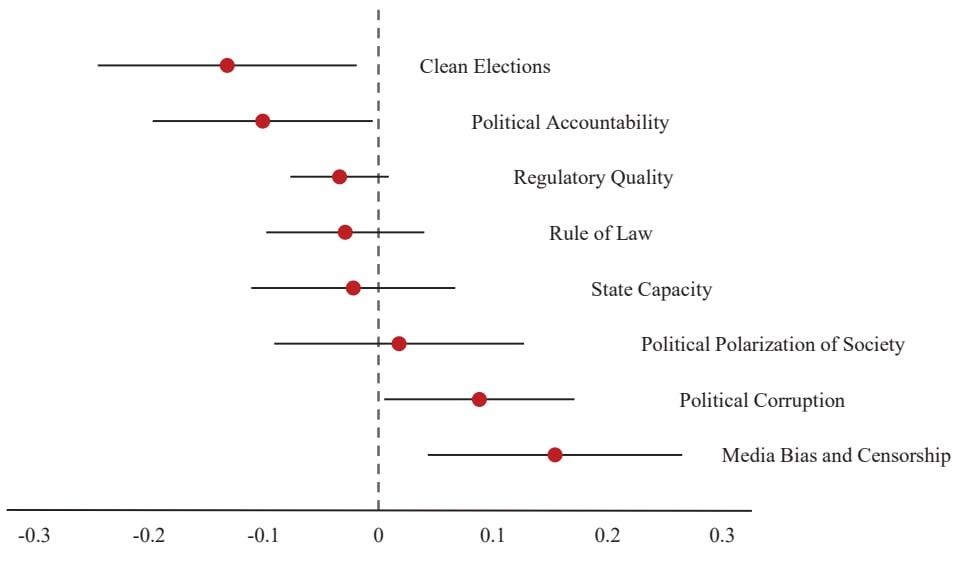

The most direct pathways are increased corruption and the erosion of clean elections. Market power is significantly associated with a decline in the quality of elections and an increase in electoral fraud and bribery. Furthermore, it exacerbates corruption across the executive, legislative, and regulatory branches of government.

Another critical channel is media control. I find a strong positive relationship between market power and media bias and censorship. This can occur through direct ownership of media outlets or if large advertisers pressure or influence the media to self-censor. When powerful firms can shape the information citizens receive, it undermines their ability to hold governments accountable.

Indeed, the analysis shows that market power decreases political accountability—the ability of citizens to sanction their leaders. Conversely, I find no significant effect on the rule of law or state capacity (such as efficiency of the state in administering services and maintaining fiscal stability). This suggests that powerful firms may not seek to break the state itself but rather to manipulate its levers for their own benefit.

Finally, I investigated whether income inequality is a key mediator between economic concentration and democratic backsliding. While theoretically plausible, the evidence does not support this pathway. The main harm arises not from widening income gaps but from the direct institutional erosion caused by corruption and political influence.

Figure 3: The Estimated Long-run Effects of Market Power on Various Institutional Indicators.

Implications for policy and research

Large firms act in their economic interest. As profit-maximizing entities, they naturally seek to protect and expand the conditions that sustain their market dominance. In itself, this behavior is not surprising. Yet when market power becomes entrenched, these incentives extend into the political sphere.

The findings of this study carry significant implications for how we understand the relationship between markets and governance. The evidence suggests that the conversation around antitrust and competition policy should be broadened beyond its traditional economic focus.

While consumer welfare and innovation remain critical considerations, this research indicates that market concentration can have profound political and civic consequences. Therefore, policies designed to promote competition may serve a dual purpose. They are not only tools for fostering dynamic and fair markets but can also be understood as investments in institutional resilience.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.