In a new NBER working paper, John M. Barrios, Filippo Lancieri, Joshua Levy, Shashank Singh, Tommaso Valletti, and Luigi Zingales explore the impact of various conflicts of interest on readers’ trust in academic research findings, uncovering significant nuances and implications for academia and policy.

Trust in academic research is crucial as academia shapes policies, informs public debates, and guides important societal decisions. This trust, however, could be affected by the presence of conflicts of interest (CoIs), situations where a specific interest of the researcher could compromise the researcher’s impartiality. Academic research in fields such as economics, medicine, and many others is becoming more costly and often depends on funding or access to databases controlled by private parties. To what extent do these relationships undermine trust in research? Despite the growing concerns, CoIs remain surprisingly understudied outside the field of medicine.

Several competition authorities share their concerns about how conflicts of interest impact antitrust research and policy.

In our new NBER working paper, we address this gap by examining how different types of CoIs shape perceptions of the trustworthiness of economic research. We surveyed academic economists and a representative sample of the United States population. Respondents were presented with vignettes summarizing high-quality research and asked to rate their trust in the findings. We explicitly noted that the research had been subject to peer review and published in a prestigious journal. Participants were then randomly exposed to various disclosure statements highlighting different forms of CoI, including monetary and career conflicts, access to data, academic/reputational conflicts, and political/ideological conflicts. The trust reduction is then the change in trust after the disclosure of a CoI.

Trust in the results declined across all groups (on average by 30%) following the disclosure of a CoI, despite the research being peer-reviewed and published in a prestigious academic journal. This decline was moderated by expertise, with average Americans experiencing greater declines in trust than “elite” economists (who publish in the top journals, see Figure 1). Nonetheless, even elite economists experienced a drop in trust.

Figure 1

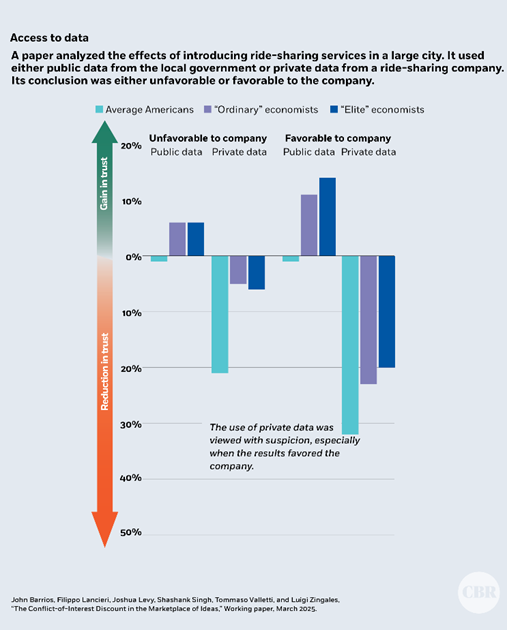

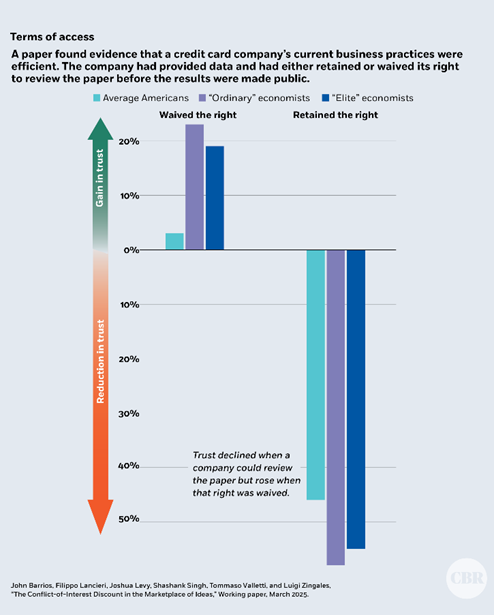

Financial incentives (such as funding) were not the sole or the most significant factor influencing trust. Instead, privileged access to data had the most pronounced effect. When research utilized private data aligned with the interests of the data provider, trust in the results decreased by over 20%. More strikingly, trust dropped by approximately 50% if the data provider retained review rights over the research outcomes, while explicitly waiving these rights increased trust by about 12%. In general, respondents expressed greater skepticism toward private data compared to publicly available government data (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Note: The images are from the Chicago Booth Review Infographic

These results highlight the growing significance of data as a key commodity in academia and raise important concerns about current journal disclosure practices regarding data access. Journals often have minimal requirements for disclosing how researchers obtain data, frequently granting waivers that limit data accessibility for replication and further studies.

Not all sources of funding create the same mistrust. Trust decreased much less when the source of the conflict was past work for the government rather than for a private party (as an expert witness in a hypothetical supermarket merger). Explicitly mentioning the payment size (USD 400,000 in our scenario) further reduced trust (see Figure 3). This finding provides context for the increasing courtroom practice of trial attorneys asking expert witnesses to disclose their compensation amounts during cross-examinations, amounts that frequently reach millions of dollars.

Figure 3

We find that experts exhibit a significant cognitive dissonance. Industrial organization economists exhibit a lower reduction in trust than financial economists when the vignette refers to a conflict in their area of expertise, but a higher reduction in trust than financial economists when the conflict regards a finance expert. The opposite is also true: financial economists distrust the IO expert more than average when the conflict focuses on antitrust, but discount less their finance peers in a consulting engagement.

Conflicts might also arise from political and ideological affiliation. Disclosing the author’s political affiliation in a paper on the effect of access to abortion decreased trust by 17%. Democratic authors are trusted less, regardless of the results, while Republican authors are trusted more if they find that access to abortion helps women’s careers, while they are trusted much less when they find it has no impact (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

These trust reductions incorporate some expectation that the published article might be conflicted even before the conflict is revealed. When we include this factor, the decrease in trust due to CoIs becomes even more severe.

Access to data and funding are crucial to academic research. Since we do not study the benefits of conflicted research, our article cannot draw any conclusions for regulating such relationships. Nevertheless, it does have some important policy implications.

First, we find that current disclosure lacks credibility: only 2% of our surveyed economists believe that academic peer economists adequately disclose their conflicts of interest. Without credible disclosure, conflicted research imposes an externality on unconflicted research, penalizing younger and more independent scholars. To reduce this externality, journals should devise some form of punishment for undisclosed conflicts.

Second, we must develop new policies for papers based on discretionary, gated private datasets. Agreements governing data access are typically confidential, creating opportunities for selective data sharing or manipulation of research outcomes. Confidential data-access agreements pose a direct threat to research transparency and replicability. Academic journals should explicitly refuse submissions from authors whose data providers retain review or approval rights beyond necessary confidentiality protections. Furthermore, journals should require public disclosure of data-access terms as a prerequisite for publication (excluding potentially sensitive payment details). Such transparency would bolster researchers’ negotiating power with data providers and strengthen the overall integrity of research.

While the above recommendations will ameliorate the problem, they will not eliminate it. Even with better rules, researchers will fully internalize the benefits from conflicted relationships (funding, proprietary data, prestige) without bearing the broader societal costs (less credible research). To fix this problem, we call for explicitly discounting conflicted papers in surveys, judicial proceedings, and promotion decisions. Our study provides an initial estimate for this discount, but further research in this area is needed.

For decades, economists have accused regulators of being captured by industry, ignoring their own conflicts. Now, the tables are turning. Regulators are finally waking up to academic capture. As the then Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter astutely summarized in a keynote address last September:

Economics teaches that incentives matter. And the inevitable incentive of that flow of money is to distort the academic dialogue and reshape expertise into advocacy.

We see this playing out from legal academia, to economics, to public policy. We see it in academic workshops, treatises and wonky empirical reports. In competition policy today, the expertise-buying game is ascendant. Conflicts of interest and capture have become so rampant and commonplace that it is increasingly rare to encounter a truly neutral academic expert.

Let me say this clearly — this will not end well. Already we see a seeping distrust of expertise by the courts and by law enforcers.

Unless we find a new way forward, we may see the critical role of expertise in competition policy dwindle away. No one should welcome that outcome.

It is imperative that the academic community effectively addresses its conflicts of interest. Failure to do so will further erode public trust and justify in the public’s eyes government interference in research, even when that interference has other goals in mind.

Authors’ Disclosures: John Barrios, Joshua Levy, and Shashank Singh report no potential conflicts of interest. Levy and Singh are both former research professionals at the Stigler Center. Filippo Lancieri received a research grant from CERRE, a Brussels’ think tank, to engage in research on data access in European Regulations. Lancieri is a Research Fellow at the Stigler Center. Tommaso Valletti was awarded a Leverhulme Major Research Fellowship to support his overall research projects. Luigi Zingales is on the advisory board of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute of the Minneapolis Fed, advises a financial startup called Jurna, produced a report on financial markets competitiveness in Chile commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank, and was compensated for speeches given at different universities and others institutions. You can find Zingales’ full disclosure statement here. Zingales is the faculty director of the Stigler Center.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.