In new research, Shaoor Munir, Konrad Kollnig, Anastasia Shuba and Zubair Shafi explore how Google uses its web browser, Chrome, to maintain its dominance in other online markets, particularly advertising and search. Their findings contribute to an ecosystem analysis of Google’s anticompetitive behavior.

On Monday, United States District Judge Amit Mehta found Google guilty of operating an illegal monopoly in online search. A separate case challenging Google’s dominance in online advertising is set to begin in September. Yet, so far, one driving force behind Google’s business remains widely overlooked: its Chrome browser. Without it, Google’s consolidation in online search and advertising would hardly have been possible to such an extent. This blind spot in current antitrust proceedings on both sides of the Atlantic also underlines that antitrust enforcement ever more relies on tech talent to hold tech companies to account and thus the need to expand this expertise in public service vigorously.

Google first released Chrome in 2008. Within a few years, the browser displaced Mozilla Firefox and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer as the most popular web browsers. Nowadays, according to StatCounter, Chrome is the most widely used browser in every country in the world except Equatorial Guinea. Its overall market share is about two thirds. Further, the core of Chrome, the so-called “browser engine,” is the foundation for many other web browsers, including Microsoft Edge, Brave, DuckDuckGo and Opera. The modern web has become unthinkable without Chrome.

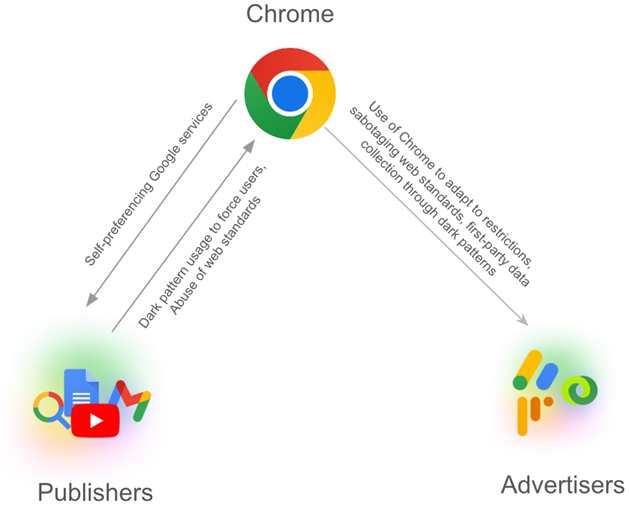

The ascent of Google Chrome is the result of significant and sustained investment by Google. This initially enabled the company to outperform its well-resourced rivals, particularly Microsoft, Apple, and Mozilla Firefox. However, given that Chrome is free and does not generate any direct income for Google, why would the company have prioritized the creation of Chrome and continue to invest in its upkeep? This is what we examined in a recent paper, forthcoming in the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law. Sundar Pichai, nowadays Google’s CEO, stated at Chrome’s launch in 2008 that “our entire business is people using a browser to access us and the Web.” Chrome was never envisioned as an ancillary service in Google’s operation. Instead, it is at the core of its business strategy. This is because it serves as a crucial link between Google’s advertising business and its other online services, particularly Google Search and YouTube—the two most visited websites in the world. This mechanism is visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Chrome was able to quickly gain browser market share despite being a latecomer to the game (Microsoft’s Internet Explorer had been out for over a decade, Apple’s Safari since 2003) in part because other browsers provided an inadequate web experience. Back then, the internet landscape was vastly different. Internet bandwidth was limited, web browsers were slow and clunky, and smartphones had only been released the year before in 2007. Most people still heavily relied on applications running on their Windows operating system, instead of using web applications like Google Docs or Gmail. Chrome changed this.

Compared to its competitors, Chrome offered a faster and sleeker web experience. Four years after its release, Chrome overtook Internet Explorer as the most widely used web browser. This wide adoption helped increase individuals’ uptake of Google’s other web applications. Nowadays, Gmail has become the most popular website in the email category, Google Drive the most popular file sharing service, and Google Workspace the most popular office suite. All these applications run exclusively in the web browser, rather than as a traditional desktop program. This shift towards web applications also means that users spend significantly more time online, use more Google services, and create more data that Google can then use for its advertising business. Given that over 80% of Google’s revenue comes from advertising and relies on vast amounts of data, Google couldn’t exist without the success of Chrome, encouraging the use of Google services and the creation of valuable data for Google.

As such, and as we document in our research, Google has pursued several strategies to maintain Chrome’s dominance over the past 20 years, including the acquisition of start-ups and competitors in numerous online services. Google’s market dominance allows it to push subpar web standards that hurt user privacy or drive out competitors. One notable example is Google’s 2010 acquisition of Widevine,the industry standard for protecting online videos or music against illicit copying. When Spotify adopted Widevine for its web player in 2017, it broke the program’s compatibility with the Safari browser and users had to switch to another browser. Widevine also reflects a radical departure from the traditional rulemaking on the internet, where standards are set by open, multi-stakeholder organizations, such as the World Wide Web Consortium or the Internet Engineering Task Force. Nowadays, these web standards are more frequently set by the most dominant browser developer, namely Google.

Another example is Google’s continued delay of restricting third-party cookies in Chrome. This technology allows Google and other companies to monitor users’ browsing activity across different websites. The collection of these user data is then leveraged to show people more targeted ads. The data are also sold via data brokers to anyone interested, which can expose user’s browsing history to unknown and potentially malicious actors. This is why other major web browsers have long since removed third-party cookies. Google announced its intention to follow suit first in 2020 and then multiple times thereafter but has still not done so. In a surprise move in July 2024, Google announced that it won’t abandon third-party cookies anytime soon.

When it comes to third-party cookies, Google is in a difficult position over protecting user privacy in Chrome while also relying on the data generated from Chrome for its core business model in advertisement. Additionally, the United Kingdom Competition and Markets Authority expressed concerns that the move away from third-party cookies might unfairly disadvantage Google’s competitors in online advertising. These competitors have relied on third-party cookies to show relevant adverts to individuals. Meanwhile, Google can rely on its own widely used services to collect data about users in a way that other, smaller competitors cannot. Additionally, as we show in our paper, Google leads in terms of adoption of first-party cookies, an alternative to third-party cookies that is significantly more difficult to implement for smaller competitors. About 80% of our studied websites used Google’s first-party cookies, followed by Facebook/Meta with 26%. Google’s strategy of delays could therefore be seen as an attempt to first make its own services ready for the transition, and to keep regulators occupied and look beyond more critical aspects of Google’s business. It also underlines the central role that Google plays in setting the rules for privacy and competition online.

Google also widely uses deceptive user interface design, so-called “dark patterns.” These dark patterns are intended to nudge users to take certain actions. For example, whenever individuals use Google services, such as Search, Docs or Gmail, on a non-Chrome browser, they receive constant reminders to switch to Google Chrome. When they login to Gmail via a competing browser, they even get an email into their inbox that suggests installing Google Chrome—potentially in violation of European Union law prohibiting unsolicited inbox advertising.

Chrome does not just bolster Google’s position in advertising and online services. It also allows Google to leverage its vast advertising revenues to push a “pay-to-play” paradigm. The most notable example of this are the direct monetary payments Google pays its competitors in web search—subject to the recent U.S. antitrust ruling. With these payments, Google seeks to become the default online search provider in competitors’ browsers. Microsoft is the only major browser developer that does not receive such payments from Google, and instead uses its own Bing online search. All other major players, including Mozilla Firefox and Apple, received large, regular payments from Google. Apple receives about a third of Google’s advertising revenue on Apple devices—amounting to about $20 billion in 2022. Meanwhile, Firefox, once having had a market share of 50% in the browser market, does not have a business arm in search or advertising, and has not been able to keep pace with Google Chrome. The market share of Firefox has now dropped to about 3%. This underlines the critical nature of integrating a browser with ancillary services.

In sum, despite Chrome’s dominance and its critical role in Google’s ecosystem, it has so far escaped antitrust scrutiny. Addressing this gap is instrumental to ensuring a competitive digital environment that fosters innovation and protects consumers. Potential remedies need further analysis but could include behavioral remedies targeting specific anticompetitive practices, such as restrictions on Google’s cross-service use of user data and on Google’s self-promotion of its own services via dark patterns. Structural remedies might involve an internal separation of Google’s divisions, or even a divestment of Chrome.

Our work points to a blind spot in current antitrust proceedings and underlines that a sound understanding of the whole technological landscape is instrumental for this work. Sadly, tech talent rarely works in public office, but instead for the very companies that the regulators wish to hold to account. This is changing. Yet, the pace is still too slow.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.