In new research, Monika Leszczyńska explores how consumers’ ideas of morality should inform government agencies and courts as they seek to update and enforce consumer protection laws. The focus is on adapting these laws to address modern business practices in the digital age. These practices involve behavioral manipulation of consumers, resulting in non-monetary damages, such as the invasion of privacy.

Companies are increasingly relying on manipulative online marketing strategies, often referred to as “dark patterns,” that exploit people’s cognitive limitations to influence their consumption choices. One common example of these strategies is “nagging,” where users receive persistent notifications on their mobile devices, urging them to share their geolocation. Scholars, legislators, and regulators recognize the risks associated with these tactics, as they have the potential to harm consumers by negatively impacting their welfare, undermining consumer autonomy, and eroding trust in the digital economy. Recent studies indicate that these techniques have a significant impact on consumer decisions. They can lead individuals to consume products and services they wouldn’t normally choose or prompt them to disclose information they would prefer to keep private.

Market forces are unlikely to resolve this issue because consumers often do not realize that these techniques are being used to influence their decisions, at least not in the moment when they are making consumption choices. Awareness might dawn on them later, leading to attempts to avoid companies employing such tactics. However, seeking alternatives—businesses that do not employ such strategies—can be costly for consumers even if such alternatives exist. This is particularly true as companies have little incentive not to use these tactics. Non-manipulative strategies tend to be less effective compared to those exploiting cognitive biases and heuristics. For the market to self-correct, companies would need to gain a competitive advantage by refraining from these dark-pattern strategies. This would entail companies investing money and effort into educating consumers about the associated dangers. The situation presents a collective-action problem: companies hesitate to invest in such an educational campaign due to the fear that other companies will benefit from their efforts without contributing.

All of this—the risks posed by these strategies and the unlikelihood that the market will self-correct—underscores the need for legal intervention. However, the legal response, especially for non-deceptive practices like nagging, remains unclear. In particular, drawing a line between acceptable persuasion or choice architecture that facilitates consumer choices and unacceptable manipulation that may harm consumers is challenging.

In my new paper, I explore a valuable benchmark for informing a legal response to these practices that incorporates public perception and moral norms applied to companies’ tactics. It shows that the factors influencing these moral assessments do not necessarily align with states’ or the federal government’s criteria for evaluating the lawfulness of dark-pattern practices under consumer protection laws. I conclude that taking into consideration consumers’ views on practices that target privacy-related decisions, potentially resulting in non-monetary harms, informs how governments can revise consumer protection laws and regulations for the digital age.

Initially, I identified the key elements of the unfairness standard, a legal doctrine to determine illegal business practices, at both state and federal levels. Through a comprehensive survey covering all 50 states, I found that in 17 states, a moral criterion plays a decisive role in determining whether a practice is deemed unfair. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), federal courts, and numerous state courts examine whether a practice, to be deemed unfair, results in or is likely to result in substantial consumer injury that consumers cannot reasonably avoid and that is not outweighed by countervailing benefits.

Historically, the FTC primarily regarded consumer injury as monetary harm. This emphasis hampers the application of the unfairness standard to online marketing, which often targets privacy choices, where proving monetary harm can be challenging. Although the FTC has recently broadened its unfairness test to include strategies resulting in non-monetary harms, how the federal courts will interpret this change remains uncertain. In addition, government agencies and courts must now reconsider what it means for consumers to reasonably avoid a business practice, which traditionally depends on consumers having freedom of choice. In online marketing, this raises a question: which strategies genuinely threaten freedom of choice to be deemed unfair?

The two sets of criteria for assessing the unfairness of trade practices—one emphasizing morality and the other including consumer injury, free choice, and cost-benefit analysis—align with two perspectives on the objective of consumer laws. One viewpoint sees consumer laws as a set of legal rules designed to enforce moral norms in markets. The other perspective focuses on consumer sovereignty, wherein the goal of consumer law is to safeguard consumers’ freedom of choice, allowing them to maximize their welfare. The latter perspective operates on the assumption that, given freedom of choice, consumers will act rationally and make decisions that genuinely optimize their welfare.

Applying the unfairness standard to online marketing strategies, whether to enforce moral norms or protect consumer sovereignty, will benefit from understanding consumer perceptions of these strategies. Both the morality of online marketing strategies and the threat they pose to consumer freedom of choice can be assessed by regulators such as the FTC or state attorneys general responsible for enforcing consumer protection laws, or by courts. However, the views of these entities may not necessarily align with those of key stakeholders—consumers. Ultimately, understanding moral perceptions and their driving factors will also help determine whether the two objectives of consumer protection law overlap when defining the scope of the unfairness standards applicable to online marketing practices. For example, do consumers perceive as less moral only those strategies that may result in monetary harm, or do they also consider non-monetary privacy-related harm?

Taking into account the elements of the unfairness doctrine and the two normative perspectives on the objective of consumer law, my empirical research explores people’s moral views on online marketing strategies. Additionally, the study investigates whether the two legally significant elements—the presence and type of injury, as well as the perceived threat to freedom of choice—drive these views.

To test this, I conducted an experimental vignette study with a sample representative of the United States population in terms of age, race, and gender. Each participant read a scenario describing a dating app that offered a free 7-day trial period. Following this period, users received a notification presenting the option to extend the app for another 30 days. I used this notification to introduce two experimental factors: the type of strategy employed to influence users’ decisions about extending the app and the presence and type of potential injury resulting from this decision.

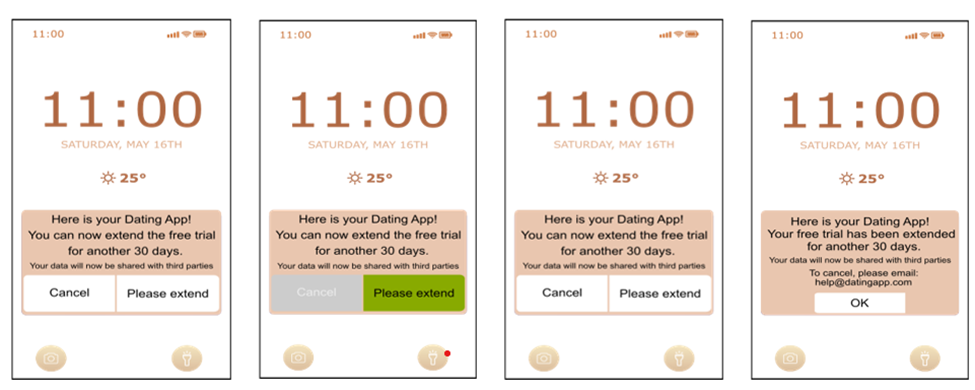

In one set of scenarios (no harm treatments), users were informed that the app would be extended for free for another 30 days. In another set of scenarios (privacy treatments), they learned that once the app was extended, all personal data users shared with the app would be disclosed to third parties. Finally, in another set of scenarios (money treatments), the app was extended for another 30 days but would now cost $9.99 per month. Figure 1 illustrates the baseline for the design of users’ choices regarding the extension, along with the three tactics used to influence their decision. After reading a scenario, participants were asked a set of questions designed to measure the perceived threat to their freedom of choice and whether they found the strategy to be morally acceptable.

Figure 1. Baseline and three strategies introduced to influence users’ decisions

A. Baseline: Shows the neutral choice design where users can cancel or extend the app.

B. Graphics: Illustrate an aesthetic design modification technique highlighting the desired decision by the app.

C. Nagging: The notification looks like the Baseline, but participants were informed that users would receive it every day.

D. Roach motel: The app is extended by default, and users can cancel it by sending an email to customer services.

All strategies presented here are from the privacy treatments, where users are informed that their data will be shared with third parties. In the no harm treatments, there was no additional information. In the money treatments, there was a sentence informing users that the app costs $9.99 per month.

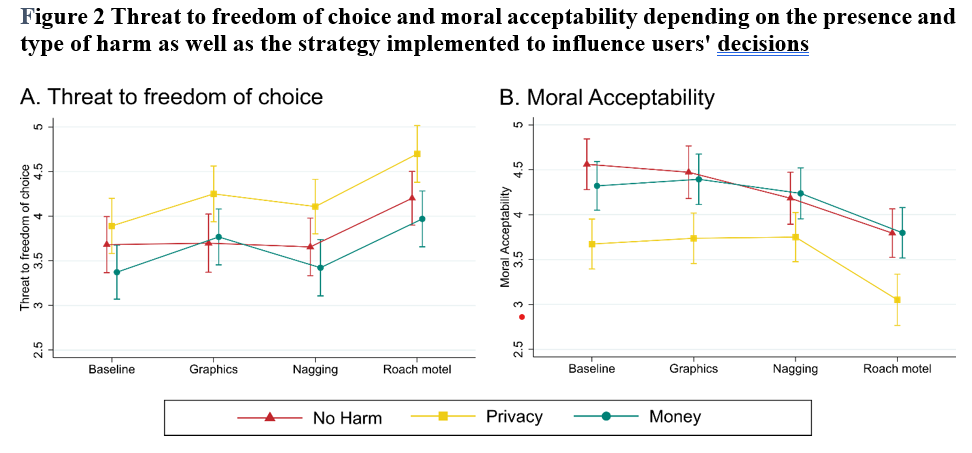

The results show that people perceive tactics that may potentially result in privacy harms as more threatening to their freedom of choice and less morally acceptable than those unlikely to lead to any harm. Simultaneously, strategies such as the “roach motel” technique, where it is easy to extend the app but difficult to cancel it, are perceived as more threatening to freedom of choice and less morally acceptable than a neutral choice design, regardless of the presence and type of harm. Finally, it is indeed the perceived threat to freedom of choice that drives the moral perception of those tactics, although there are certainly other considerations playing a role in those assessments.

What do these findings imply for the unfairness standard?

Firstly, if we believe consumer law should take into account the perceived threat to freedom of choice posed by online marketing strategies as a factor influencing consumer welfare, as well as people’s moral views on these strategies, it should also scrutinize practices likely to lead to privacy harms.

Secondly, if the threat to freedom of choice is significant, proving likely consumer injury should not be necessary.

Lastly, if state courts use morality to judge unfairness, they should consider whether it threatens consumer freedom of choice or is likely to lead to consumer injury, understood very broadly to include privacy harms. Such practices likely violate moral norms.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.