In new research, Elise Blasingame, Christina Boyd, Roberto Carlos, and Joseph Ornstein explore how the Trump administration used a quota policy for immigration judges working under the Department of Justice’s purview to influence how they adjudicated cases. The authors find the policy successfully nudged more judges to rule against immigrant plaintiffs.

The Trump campaign has made no secret of its plans to further expand the scope of executive branch power and reign in independent federal agencies should he return to office in 2025. But controlling the behavior of lower-level actors within the federal bureaucracy has been a long-standing challenge for presidents and their administrations. In our new study, “How the Trump Administration’s Quota Policy Transformed Immigration Judging,” we demonstrate how Trump was able to use a controversial 2018 performance quota policy to significantly alter the behavior of immigration judges—particularly among those judges who typically favor noncitizens’ claims in immigration cases—to advance his agenda to drastically reduce immigration. Our findings have significant implications for immigration judge independence, due process protections for noncitizens, and presidential power.

In the United States, immigration judges are part of an administrative court under the Executive Office of Immigration Review housed in the Department of Justice. Immigration judges make decisions in hundreds of thousands of noncitizen-removal cases yearly. Judges consider a variety of case types, including, for example, asylum claims, requests for adjustment of immigration status, and related immigration matters. Immigration judges are directed to use independent judgment as they make decisions based on the law and facts in the cases before them—just as is the case for other U.S. judges. What is different for immigration judges, however, is that they are employed by and serve as bureaucrats within the Department of Justice, meaning that politicians like the president and attorney general hold power to curtail their judicial autonomy. No comparable threat to judicial independence exists for most other federal judges, like those serving on the U.S. district and circuit courts or the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 2018, then Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a policy requiring immigration judges to complete a minimum of 700 cases per fiscal year and have no more than 15% of cases overturned on appeal, meaning that immigration judges had to be mindful of what the Trump-appointed Board of Immigration Appeals and attorney general wanted in their decisions. While the stated aim of the policy was to reduce the backlog of immigration cases growing exponentially year-over-year, the political motivations were clear: to pressure immigration judges to order more immigration removals and deportations as quickly as possible. From building the wall at the southern border, to family separation policies in detention centers, Trump was unequivocal in his aims: waging one of the most aggressive anti-immigration campaigns in recent history. The policy was certainly controversial and led some judges to quit. The immigration judges’ union campaigned against it.

Previous presidents have attempted to control immigration judges’ outputs to meet their policy goals but were largely ineffective. This quota policy was different because it credibly threatened both job security and promotion opportunities for judges if they failed to meet the policy requirements.

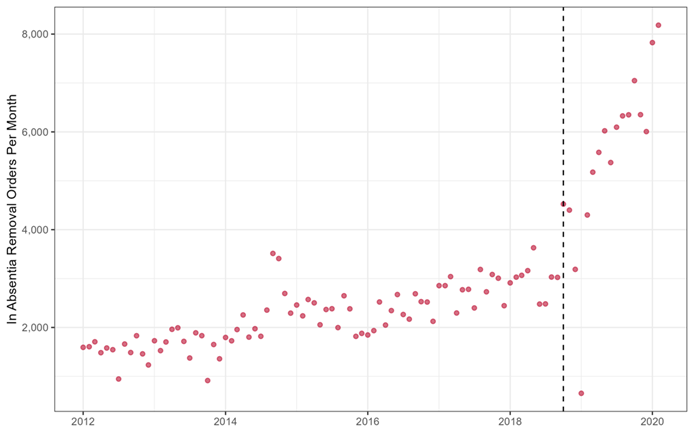

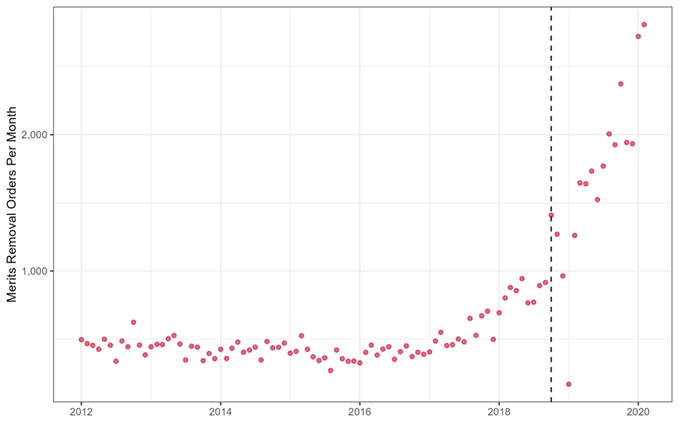

To examine the effect of the policy on judges who were hearing immigration cases before and after the policy, we focus on two outcomes: cases decided in absentia and those decided on the merits. When an immigrant-petitioner fails to appear or shows up late for their assigned case hearing, the judge has the discretion to order the petitioner to be removed (deported) in absentia, meaning they were absent for their court date. In other cases where an in absentia removal order is not relevant or does not occur, a judge considers the facts of the case and decides whether to order a removal based on the merits of their case. Merits and in absentia orders offer immigration judges an avenue for complying with the Trump quota policy’s aim for more removals, with in absentia orders also furthering the policy’s emphasis on speedy removals.

Figure 1 shows the monthly rates of cases decided in absentia before and after the policy. We see a significant increase in in absentia removal orders in the year after the policy goes into effect, corresponding to an additional 5,000 noncitizens who were ordered removed post-policy.

Figure 1

But not all judges responded the same way to the policy. Our analysis focuses on comparing the individual behavior of those judges who heard cases both before and after the October 2018 policy went into effect. We examine the effect of the policy on immigration judges based on specific characteristics such as partisanship, gender, ethnicity, and prior work experience. Our results indicate that Democratic, Latino/a, and female judges, among others who were more likely to rule in pro-noncitizen directions pre-policy, were the judges most likely to increase their average rates of issuing in absentia removals (by as many as 10 percentage points) with the implementation of the policy. This tracks with our expectations given that more conservative judges and those with prior experience working for the government (think judges who used to work as attorneys for the Department of Homeland Security) were already issuing case decisions aligned with the administration’s preferences more often than their colleagues before the policy’s implementation.

For decisions based on the merits, Figure 2 shows a similar increase in removal orders post-policy. To provide context, before the quota, immigration judges ordered less than 1,000 non-detained immigrants removed on the merits of their cases each month. Within a year of quota implementation, the merits removal rate rose to nearly 2,000 per month. Again, we find statistically significant increases in the likelihood of issuing merits removal orders for those judges who were more likely to rule in favor of noncitizens before the policy took effect.

Figure 2

Implications for Immigration Policy and Beyond

Immigrants must navigate an exceptionally complex system, often without proper legal representation, in what feels like “refugee roulette” to borrow a phrase from Jaya Ramji-Nogales, Andrew Schoenholtz, and Philip Schrag (2007). As researchers have long found, and our findings reiterate, noncitizens’ experiences in U.S. immigration courts are highly variable depending on the court and judge assigned. With the quota policy, those judges who may have initially been more sympathetic to the extreme difficulties faced by immigrants and their families were significantly less likely to issue a supportive ruling. Moreover, seeking relief through the appeals process is extremely difficult, costly, and unlikely to succeed (especially for those removed in absentia). In each of the hundreds of thousands of cases we reviewed, the immigration judge holds the potential to irrevocably change the lives of petitioners awaiting a decision in their case.

These findings also add further fuel to the calls from advocates and interested observers to remove the immigration court from under the DOJ to a more independent federal court. If individual case outcomes for thousands of immigrants can be politically influenced as dramatically as our data indicate, it calls into question the level of independence immigration judges actually have in deciding cases.

While there is no consensus on this issue, Republicans and Democrats do agree that the ever-growing backlog of cases remains a major challenge to the administration of the immigration court system. Between 2018, when the policy was issued, and today, the backlog of cases multiplied from about 650,000 to more than 2 million cases. These are immigrants, including roughly 40,000 detained, awaiting adjudication. While we provide evidence that the political aim of the policy was achieved, there remain questions regarding the efficacy of the policy toward its stated goal of reducing the backlog.

The immigration judge quota policy was revoked under the Biden administration, but should Trump be re-elected in 2024, he will likely institute a similar policy to influence the incentives and decision-making of immigration judges and other bureaucrats. This case study may serve as a blueprint for presidents in growing executive power and influencing the policy outputs of bureaucrats in ways previously viewed as implausible. This is especially true for agencies overseeing hot button issues like immigration. As Congress continues to avoid legislating on immigration-related matters, what happens next with presidential efforts to constrain bureaucrat behavior will be important to watch.

Authors’ Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of ProMarket, the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.