Grocers Kroger and Albertsons want to merge, which would make them the second biggest retail food chain and, according to them, enhance their ability to compete with Walmart and Costco and offer lower prices to consumers. Christine P. Bartholomew writes that the promises of more competition and lower prices for consumers are unlikely to manifest, and thus the Federal Trade Commission should block the deal.

The potential merger between Kroger and Albertsons moved a step closer to completion last month when the grocery chains sold off $1.9 billion in assets. As part of its current “charm campaign,” the companies are framing this divestiture as a sufficient prophylactic against any anticompetitive effect from combining the nation’s second and fourth largest grocery chains. However, this proposed merger would require a significant clean-up to fulfill its promises.

A core concern behind Section 7 of the Clayton Act is consumer protection. Section 7 prohibits mergers that might lessen competition, since such deals risk creating fewer choices and higher prices. Others have already lambasted the merger for its potential to harm workers and exacerbate food deserts. As it stands, the proposal also bears three markers of a deal that benefits Kroger and Albertsons’ bottom lines at a cost to consumers: it would increase market concentration; risks inflating competitor prices; and relies too heavily on a dicey divestiture plan to protect competition.

I: Increased concentration will not improve competition

Merger analysis requires uncovering any potential anticompetitive impact. If the merger goes through, 70% of the national retail food market would be consolidated in three firms: Walmart, Kroger-Albertsons, and Costco. The retail grocery market has already become more concentrated in recent decades, morphed by years of consolidations and acquisitions. Mergers have driven out smaller regional chains, as well as privately owned stores. Compared to 25 years ago, there are roughly one-third fewer grocery stores. Market share for the top four largest grocery retailers, Walmart, Kroger, Costco, and Albertsons grew 46% from 1993 to 2019.

Kroger and Albertsons contributed to this concentration. Between 1983 and 2014, Kroger acquired 15 grocery chains. In 2015, Albertson acquired Safeway, a deal that joined 2,230 stores, 27 distribution facilities, and 19 manufacturing plants across 34 states and the District of Columbia.

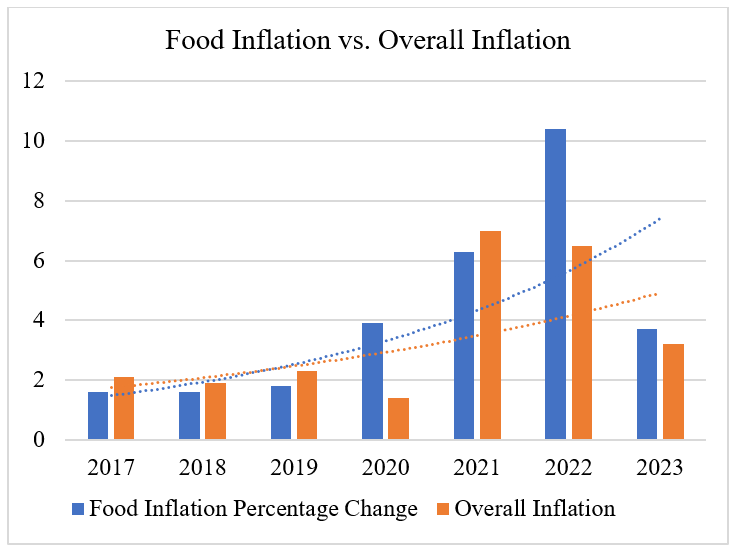

At the same time, other players in the food supply ecosystem, including beef and chicken processors, also consolidated. The result: soaring prices. Since 2018, the Consumer Price Index for all foods increased 20.4%, outpacing national wage increases. Food inflation currently exceeds historical average rates, even after dropping in 2023:

Supporters of the merger would rightly point out antitrust laws do not condemn mergers simply because they increase market share. Nor does an increased market share automatically equate to higher prices. Nationally, the additional market concentration from this merger would not exceed key thresholds when analyzed using the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI), a primary measure used to identify dangerous mergers. One calculation of the merger found it would increase the food retail industry HHI by 28 points—below the one-hundred-point increase that regulators generally use to decide whether to block a merger in a moderately or highly concentrated market.

National market shares, however, mask the merger’s danger. In more local geographic markets, retail sale of food and other grocery products in supermarkets is already highly concentrated. Post-merger Walmart and Kroger-Albertsons would control more than 70% of the grocery market in over 160 cities. This would tempt them to increase consumer prices in areas where it has become the dominant retailer. Consider Walmart: in areas where it is the primary grocery retailer, it has raised food prices. A lack of competition meant it had no reason to maintain its “Every Day Low Prices.” That Kroger-Albertsons would take a different route than Walmart with this local market power is dubious.

Admittedly, the concerns raised so far are speculative. But merger analysis turns on supposition; Section 7 of the Clayton Act focuses on whether a merger might—not will—harm competition. As discussed, the specter of such harm exists. This means regulators will have to prognosticate whether sufficient procompetitive justifications exist to outweigh the merger’s anticompetitive effects. On this second question, the Kroger-Albertsons deal falls short.

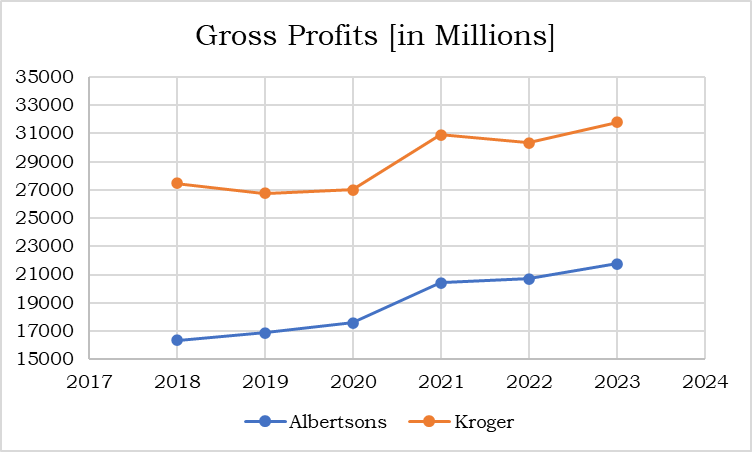

Kroger and Albertsons will likely contend merging would allow them to better compete with Amazon, Costco, Walmart, and Aldi. Costco, however, controls less than one-eighth as many stores as Kroger and Albertsons combined. Even Amazon, a notorious player in the world of antitrust, controls less than 2% of the grocery market. As for Walmart, Kroger and Albertsons already compete successfully, having increased their profits over the last few years despite Walmart’s growth.

That a competitor is undercutting Kroger-Albertsons’ ability to generate greater profits does not make a merger procompetitive. Should the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) accept the argument that mergers are justified because of the threats posed by Walmart and Amazon, it would open the floodgates for future mergers. Players across multiple industries face competition from these behemoths.

II: The Waterbed effect will force smaller competitors to raise prices

Further, how the merger allows Kroger and Albertsons to compete is cause for concern. Experts point out that the merger would afford Kroger-Albertsons greater buying power to negotiate lower prices for necessary inputs, reducing internal costs. Increased buying power can benefit consumers if the buyers pass on savings. But monopsony power can also spell danger. Buyers can use their power to worsen the terms for less powerful buyers. Prices go down for the dominant buyer but rise for others, a phenomenon called the “waterbed effect.” This effect risks less potential price competition from smaller rivals.

Currently, consumers benefit from downstream competition. While Kroger and Albertsons are losing market share to Walmart, they are also losing ground to discount outlets. Aldi is increasingly placing competitive pressure on Kroger and Albertsons. Even dollar operators like Dollar General and Dollar Tree have expanded their food offerings. A merger risks compromising these competitive forces by allowing Kroger-Albertsons’ buying power to inflate input costs for these smaller, low-cost operators. The result: fewer discount options for consumers.

Some are skeptical of the waterbed effect in its entirety. They contend the link between buying power and consumer prices is too attenuated. Others retort by pointing to Walmart’s buying power as the source of its dominance. The FTC appears poised to wade into this debate. Staffers at the agency have already reached out to farming, food desert, and smaller grocery chain experts. Such inquiries could help the agency assess the merger’s potential impact on supply chains.

Setting aside the waterbed effect debate, the real question is what consumer prices will be in future years, when the dust settles after any initial investments by Kroger-Albertsons to lower prices. To waylay concerns about the merger, the companies have promised to reinvest $500 million to lower prices; $1 billion to improve associates’ wages and compensation; and yet another $1.3 billion in more ambiguous investments like “enhanc[ing] the customer experience.” Whether the gains from its increased buying power and other merger efficiencies would be sufficient to finance these pledges is far from clear.

Lofty promises to justify a merger are hardly unique: proposed mergers are often laden with pledges to lower prices and enhance competition. At least in the supermarket industry, however, such assurances ring hollow. A 2012 FTC working paper analyzed the impact of 14 horizontal mergers in the supermarket industry on consumer prices. Like most mergers, many of these deals vowed to usher in lower prices. In roughly 29% of these mergers, these vows were not honored: no price decreases occurred. More troubling, though, in over a third of the studied mergers, prices increased. While prices only increased just over 2%, any food price increase can have significant consequences. Thirty-one percent of households already report having skipped or reduced meal sizes because of fiscal concerns. Most of these increases occurring in mergers involved highly concentrated markets—markets like those that would be created by a Kroger-Albertsons merger.

III: A questionable divestiture

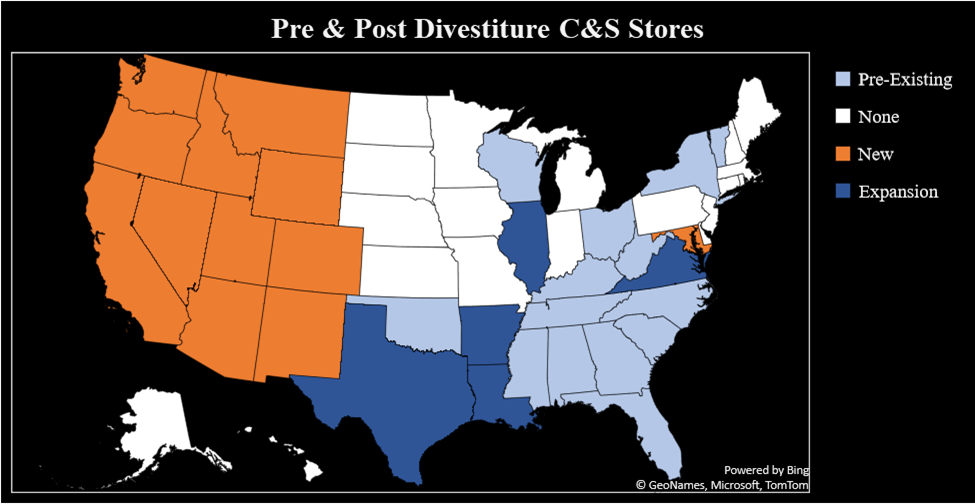

Perhaps anticipating regulatory skepticism, on September 8, 2023, Kroger and Albertsons shared its plan to divest assets to C&S Wholesale Grocers. Kroger-Albertsons announced the plan as “a key next step toward completion of the merger by extending a well-capitalized competitor into new geographies.” A divestiture might seem like an easy answer to a messy proposed merger. In fact, in the 1960s and 70s, courts regularly required them as a remedy to otherwise risky mergers. Indeed, Kroger and Albertsons are proposing to sell off significant assets: 413 stores, eight distribution centers, two offices, and many brand names. This sell-off unfortunately generates a third cause for concern.

Divestiture is not a panacea. Its utility as a remedy varies, as evidence suggests divestitures can drive prices up roughly 7.7%. Moreover, Albertsons’ past divestitures call into question its ability to structure a sell-off that benefits competition. In 2014, as part of Albertsons’ merger with Safeway, the two grocery chains sold 168 stores to Haggens, a small, northwestern chain. Albertsons pitched Haggens as poised to become a viable competitor capable of competing against the newly merged entity. Less than a year later, Haggens filed for bankruptcy and shuttered the doors of 27 acquired stores. It then sued Albertsons, alleging in part that Albertsons overstocked stores with perishable fruit and meats, provided inaccurate pricing information (which contributed to higher prices), and failed to perform necessary maintenance on stores and equipment.

The litigation settled prior to a judicial determination as to the legitimacy of the allegations. As part of the bankruptcy, Albertsons was able to reacquire 33 previously divested stores at a fraction of their original value. Consumers ended up paying excess grocery costs when Haggens operated the stores, then felt the pinch from reduced competition after Albertsons reacquired the stores.

Admittedly, the current divestiture is notably different from Albertsons’ “rotten deal” in 2015. C&S has experience operating grocery stores (Grand Union and Piggly Wiggly) in the Midwest and Carolinas. And there is evidence of regional grocers successfully expanding beyond their territorial reach. Pre-acquisition, Haggens owned but 18 locations; C&S owns 515. C&S’s experience, though, lies primarily as a wholesaler. The divestiture almost doubles the number of retail outlets C&S will operate—going from 515 to 928. It requires C&S to greatly expand in states in which it only has a modest presence. Consider, for example, Arkansas. The divestiture results in a 280% in-state growth. Further, the divestiture will necessitate expanding into the west coast, where it has no prior experience or brand loyalty.

It remains to be seen whether C&S has the retail operating expertise to shoulder this rapid expansion. With these open questions, it is difficult to feel confident that C&S can serve as a meaningful competitive check on post-merger Albertsons and Kroger’s dominance.

Conclusion

Despite these open questions, the CEOs for Kroger and Albertsons continue to make the case that their merger is a good thing. They have taken their case to the people, issuing an op-ed in the Cincinnati Enquirer in an effort to assure the public that the merger will not result in store closures, loss of jobs, or increased grocery costs. Could the divestiture be sufficient to protect the retail grocery store market? Potentially. Could the merger result in lower prices to consumers? Perhaps. But from an antitrust standpoint, a merger needs more than the possibility of gain; so long as a merger might tend to lessen competition, the Clayton Act prohibits it. As it stands, the Kroger-Albertsons deal is stained with uncertainty. Too great a risk remains that consumers will be left paying to clean up the mess from this merger.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.