Xerox invented modern copier technology and was so successful that its brand name became a verb. In 1972, U.S. antitrust authorities charged Xerox with monopolization and eventually ordered the licensing of all its copier-related patents. As new research by Robin Mamrak shows, this antitrust intervention promoted subsequent innovation in the copier industry, but only among Japanese competitors. Nevertheless, their innovations benefited U.S. consumers.

Competition authorities in many countries have tightened their antitrust policy in recent years. In the United States, this has raised concerns that stricter antitrust enforcement against domestic incumbents could undermine the pioneering role of American companies in the high-tech sector, as it may particularly allow foreign competitors to catch up. For example, a comment in The Wall Street Journal warned that “[a]ntitrust action against leading U.S. tech companies would shrink American dominance of the world’s fastest-growing industry.” Similarly, Big Tech executives have argued that antitrust charges against their companies would only help China.

In a recent working paper, I present empirical evidence on the impact of antitrust enforcement on (foreign) innovation by analyzing the Xerox case in the 1970s. The results show that U.S. antitrust action against Xerox promoted innovation in the target industry, but only among Japanese competitors.

Xerox Corporation was the de facto monopolist in the U.S. market for plain-paper copiers throughout the 1960s. As a little-known company, Xerox achieved its breakthrough in 1959 when it launched the Xerox 914 office copier. The fully automated machine commercialized a novel copier technology known as “xerography” that is still widely used today. Xerox’s technology was superior to that of competitors, as it could produce dry copies within seconds, was easy to operate, and could be used with ordinary plain paper. Xerox had protected its copier technology through more than 2,000 patents and strictly refused to grant licenses to any other manufacturers of plain-paper copiers. Xerox also used patent infringement suits to block entry by competitors who developed their own patented technologies. For example, when IBM introduced its first plain-paper copier in 1970, Xerox immediately sued for patent infringement, initiating a legal battle that lasted for several years.

In 1972, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed an antitrust complaint against Xerox that alleged monopolization of the copier market. At that time, Xerox’s share in the rapidly growing market was close to 95%. Xerox was accused of hindering effective competition in plain-paper copiers through its strategic use of the patent system and anticompetitive pricing policies. In 1975, Xerox settled with the FTC by signing a consent decree. As the key remedy, Xerox was ordered to license all its domestic and foreign copier-related patents to any third parties. Xerox had to grant the first three licenses to each firm royalty-free and could then ask for reasonable royalties that were not to exceed 1.5% of the licensee’s revenues.

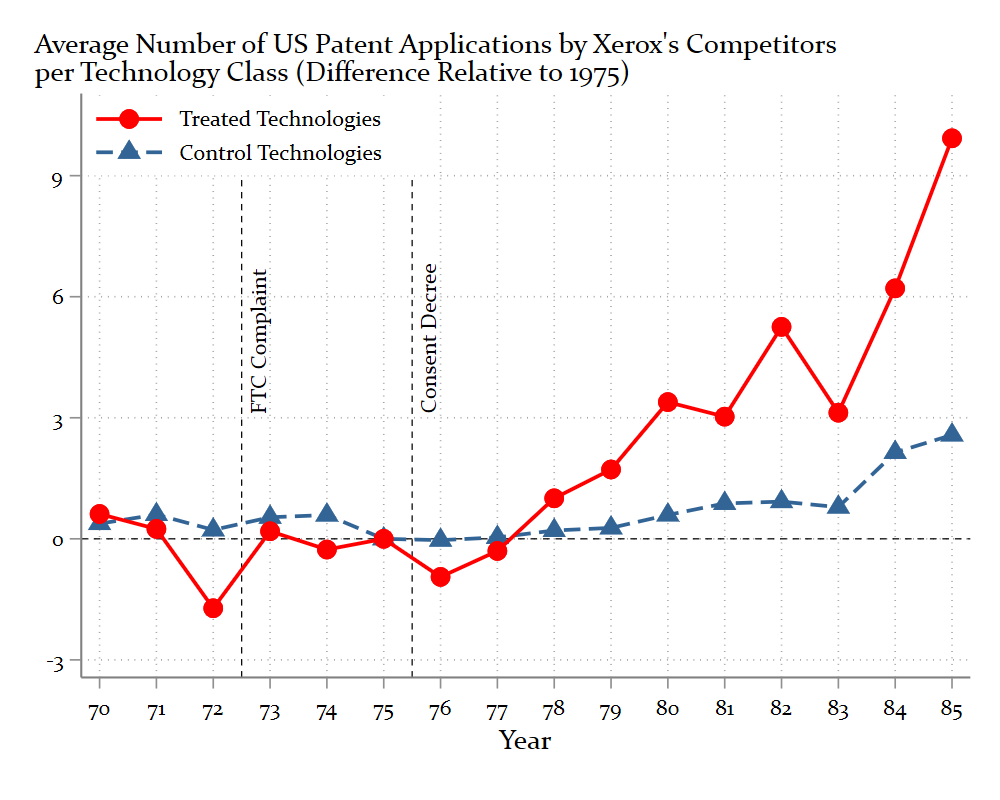

To investigate the impact of the Xerox case on subsequent innovation, I look at the number of patents filed in the U.S. by firms other than Xerox or its subsidiaries. All patent applications are assigned to a technology class. This allows me to compare patenting in fields where Xerox patents became available for licensing (= treated) to patenting in fields where no Xerox patents were licensable (= control). Put differently, treated technologies capture copier-related technology classes that were affected by antitrust action against Xerox, whereas control technologies classes do not. The figure below shows the average annual number of U.S., patent applications by Xerox’s competitors per technology class in these two groups, relative to 1975.

As the figure reveals, there was a relative increase in U.S. patenting in copier-related technologies after the settlement of the antitrust case. The corresponding regression estimates indicate that antitrust enforcement against Xerox led to an additional 160 patent applications in the U.S. per year after 1975. This represents an economically meaningful increase in patenting in copier-related technologies by around 1.4%. Thus, compulsory licensing of Xerox’s patents promoted innovation by other firms in the copier industry, as Xerox’s competitors used the newly available technology for follow-on research and either directly or indirectly built on Xerox’s patents. In contrast, as my research further shows, Xerox itself only modestly reduced its patenting after 1975. In summary, the empirical results indicate that the overall impact of the antitrust case on subsequent innovation was positive.

Interestingly, the main beneficiaries of access to Xerox’s technology were competitors from Japan. When separating the number of patent applications by applicant country, I find no effect of the antitrust case on patenting by U.S. firms. Instead, the increase in copier-related patenting after 1975 is primarily driven by Japanese applicants. Among them, only established firms but not start-ups increased their patenting. Moreover, the positive innovation effect was most pronounced for Japanese firms with extensive prior patenting experience in copier technologies. This indicates that potential competitors from Japan were most successful in building on Xerox’s technology.

The finding that Japanese rivals increased their innovation following the antitrust case is in line with historical narratives about the development of the copier industry. Prices fell rapidly as more and more firms entered the plain-paper copier market. Among the entrants, American copier producers such as IBM or Kodak started competing with Xerox in the high-volume market segment where Xerox made most of its sales. For IBM, entering the high-volume segment may be explained by the potential to exploit economies of scale from the company’s existing distribution network for mainframe computers.

Conversely, Japanese entrants such as Canon, Konica, Minolta, Ricoh, and Sharp strategically focused on the lower end of the copier market. They produced machines that were cheaper, smaller, and designed for lower volumes than existing plain-paper copiers. This business model was different from that of most American copier producers and is considered one of the key reasons for the Japanese success. Consistent with this narrative, I show that Japanese competitors filed a higher share of patents that contained words in their title or abstract that can be associated with smaller copiers. Moreover, their innovation activity expanded to new technology fields, while there was no reduction in the quality of inventions. Thus, antitrust action against Xerox not only affected the rate but also the direction of subsequent innovation.

What can we learn from these findings regarding today’s concerns that stricter antitrust enforcement may undermine the American dominance of the high-tech sector? The evidence from my paper shows that such concerns are worth investigating. In the case of Xerox, U.S. antitrust intervention primarily helped foreign competitors to build on Xerox’s technology. However, this result is not due to some of the competitors being Japanese. Instead, Japanese entrants employed a different business model that allowed them to expand the market for plain-paper copiers to the lower-volume segment, which had been ignored by Xerox. This suggests that society lacked some innovations during Xerox’s patent-protected monopoly. In that way, the antitrust case against Xerox also brought enormous benefits to American consumers. They experienced lower prices and more innovative copiers, irrespective of whether the innovators were Japanese.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.