“Consumer welfare” as an objective of antitrust law and regulation has its origins in several vague and even conflicting ideas of how to evaluate the impact of market consolidation. However, many of these ideas identify consumer welfare with higher market output and lower prices. Herbert Hovenkamp and Fiona Scott Morton argue that this definition of consumer welfare provides courts and antitrust regulators with a metric to judge the potential harmful effects of mergers and acquisitions that is superior to other antitrust goals, including protecting the “competitive process” and limiting firm “bigness.”

The Stigler Center’s 2023 Antitrust and Competition conference seeks to answer the question: what lays beyond the consumer welfare standard? In advance of the discussions, ProMarket is publishing a series of papers on the infamous consumer welfare standard. This piece is part of that debate.

The Sherman Act (1890) stated its offenses with economic language: “restraint of trade” and “monopolize.” To these the Clayton Act (1914) added “may be substantially to lessen competition” or tend to “create a monopoly.” The only exception is the Robinson-Patman Act, passed in 1936, which permitted injury to a particular competitor in lieu of harm to competition. Nevertheless, Supreme Court antitrust decisions did not mention “consumer welfare” until the 1970s—once in granting antitrust damages to consumers and another in a dissent by Justice William Brennan from the Supreme Court’s approval of several banking mergers by a subsidiary of Citizens and Southern National Bank. Usage picked up in the 1980s, including well known Supreme Court decisions in NCAA, which the plaintiffs won; and the Jefferson Parish tying case, which the plaintiff lost.

Long before the courts used “consumer welfare,” they measured antitrust goals by two metrics: changes in output or changes in price. Early decisions applying both sections of the Sherman Act used phrases such as “restrict output,” “limit production, output,” or “restricting output.” They drew this idea from pre-Sherman Act cases that described agreements that restrain trade with terms such as “enhance the price” or “limit the supply.” More recent Supreme Court decisions continue to use it, including Trial Lawyers (“constriction of supply”) Northwest Wholesale (“decrease output”), Indiana Dentists (“reduction of output”), NCAA (“output limitation)”, Matsushita (“restricting output and raising prices above the level that fair competition would produce”), AmEx (“reduced output, increased prices, or decreased quality”); and Alston vs. NCAA (“reduce output and increase price”).

Interpretation of the Clayton Act is similar. A 1909 decision interpreted a state antitrust “lessen competition” provision to mean “restraint of trade.” A 1922 Clayton Act exclusive dealing and tying decision concluded that “the only standard of legality with which we are acquainted is the standard established by the Sherman Act….” That year, the Supreme Court condemned a dress pattern maker’s exclusive dealing requirement, relying on Sherman Act cases that spoke of “enhancement of prices” as the evil. In 1935, the Supreme Court refused to condemn General Motors’ requirement that dealers use only its own repair parts when the market was more competitive. Then in 1936, the Supreme Court condemned IBM’s tie of data cards based on an 80+% market share. Without tying, “a competing article of equal or better quality would be offered at the same or at a lower price.” The popular “leverage” theory of tying arrangements adopted that observation until the Chicago School critiqued it in the 1950s. That theory identified the harm from tying as higher prices in the tied product. Justice Louis Brandeis analogized the practice to a patentee’s attempt to fix the price at which a patented article could be resold.

Consistent usage of output and price as signs of antitrust harm indicates that from the beginning, judges understood the relationship between monopoly, output, and price. Monopoly was their concern. As a result, the debate today over “consumer welfare” has taken place on two playing fields. One is the courts, where the concern with lower output and higher prices has consistently dominated. The term “consumer welfare” largely supplies some rhetoric, but no judicial decisions to date have identified a conflict between greater welfare and higher output. The second playing field is academic legal and economic literature, where the consumer welfare debate is fierce but has very largely occurred over the courts’ heads.

A useful definition of “consumer welfare” is that antitrust should be driven by concerns for trading partners, including intermediate and final purchasers, and also sellers, including sellers of their labor. These all benefit from high output, high quality, competitive prices, and unrestrained innovation. Higher output and lower prices are good indicators of competitive benefit, and there is little practical difference between the way courts talk about antitrust harm and the idea of “consumer welfare.” The definition leaves many issues of implementation unresolved. That is, the “consumer welfare” principle does not write specific rules but rather limits the range of inquiry. For example, it suggests that merger law should focus on mergers that lead to reduced output, higher prices, lower quality, or reduced innovation. It does not tell us whether a merger of two firms with, say, 15% market shares triggers this concern. That depends on economic theory and the empirical record established by previous similar mergers.

Williamson, Bork, and consumer welfare

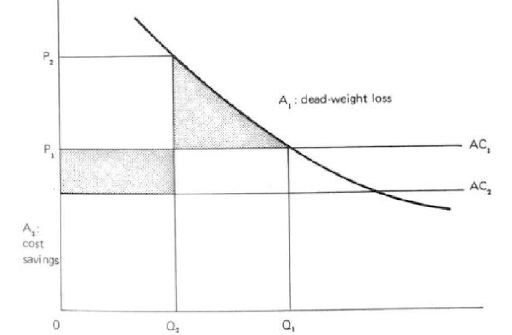

Not everyone has followed this playbook. In the 1960s, economist Oliver Williamson modeled a practice that reduced output and raised prices but produced offsetting efficiencies. The question was whether the efficiency gains offset the competitive losses. Bork later borrowed this model, illustrating a situation where output drops by roughly one-half (Q1 to Q2) but also produces significant (assumed) efficiencies because costs fall from AC1 to AC2. The result of this merger is, first, deadweight loss from lower output which Williams and Bork assumed to be offset by the efficiencies. The remaining effect is a large wealth transfer from consumers to producers. Because these resources simply change ownership, Bork and Williamson regarded the transfer as neutral. With this neutrality assumption in hand, within the Williamson-Bork model welfare could go up even as output decreased, or vice-versa:

Bork never explained how such dramatic efficiencies could occur even as a firm reduced its output. Most efficiencies (for example, economies of scale) assume increased output. Because per unit fixed costs decrease as output increases, Bork must have been assuming a firm with low fixed costs, with efficiencies coming from lower variable costs. But in that case, what was the source of the monopoly power? Further, the Bork figure showed the tradeoff between the deadweight loss and efficiency gains that accrue to a single firm. But for mergers that facilitate oligopoly or collusion, every firm in the market charges higher prices, while the efficiency gains accrue to only the merging firms. For example, in a merger of two firms each with 20% market shares, the efficiency gains apply only to the post-merger firm’s 40% of sales. The higher prices from increased oligopoly would apply to the entire market. In that case the model understates the losses by 2 ½ times.

Most importantly, Bork did a world of disservice by taking Williamson’s model, which he had correctly named “welfare tradeoff,” and renaming it “consumer welfare,” even when it led to higher prices and lower output. This misuse of the term “consumer welfare” has had two harmful effects. On the political right, given Bork’s view that efficiencies cannot be measured but should simply be assumed, it approved practices that lower consumer surplus but enlarge firm profits. At the other extreme is the view that efficiencies should simply be disregarded, condemning some practices that lead to higher output and lower prices.

The merits of consumer welfare as an antitrust goal

Consumers are generally best off when market output is high, prices are low, quality is high, and innovation is unrestrained. Some complain that output and welfare sometimes move in opposite directions. That could be true in the case of “demerit goods,” such as opioids, alcohol, or liquor, where welfare may actually decline as more is consumed. Nevertheless, antitrust policy has consistently treated alcohol and cigarettes exactly as it treats any other good, perhaps because they are usually regulated by government entities that handle public health or dangerous products.

The historical record, and sound argument, indicate that antitrust policy should focus on higher output, lower prices, higher quality, and unrestricted innovation. Efficiencies count, but only to the extent that they generate these outcomes: that is, where efficiencies lead to output at least as high and prices lower than prior to the challenged practice. The 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines—which never use the term “welfare”—accept an efficiency defense to a presumptively unlawful merger only if it “is not likely to be anticompetitive” in any market. Since the Guidelines’ basic goal for merger policy is to prohibit mergers that “create, enhance, or entrench market power,” that is effectively saying that the efficiencies must be sufficient to hold output and price to pre-merger levels. The Guidelines’ treatment of mergers with anticompetitive unilateral effects is concerned about the post-merger firm’s ability to raise price “above the pre-merger level.”

One value of this approach is that it evades the objection some have raised that the merger law never states an efficiency defense. Under the Guidelines approach, however, no efficiency defense is necessary. Proof of efficiencies is not required if there is no competitive harm in the first place.

So what does the use of the word “welfare” add? The term refers mainly to the surplus that consumers receive when they value something by more than its purchase price (or that sellers obtain when they sell something for more than its costs). For example, if a consumer is willing to pay $8 for something that costs $6, that transaction yields a $2 surplus. Estimating welfare changes requires knowledge about output and price changes, and also about the shape of the demand curve in the relevant region. If quality increases or price declines and nothing else changes, consumer welfare increases as well. Consumers buy more because the price has gone down or quality has improved. Those changes make consumers better off.

When an economist examines a practice and concludes that it increases “welfare,” the evidence supporting that claim is commonly that the practice increased output or reduced price. Even Brandeis, a populist, understood the importance of output. In 1931, he refused the government’s request to condemn a patent-sharing joint venture after pointing out that the government made no attempt to show restricted market production and, given the venture’s 26% market share, that was unlikely. On this issue, Brandeis was a consumer welfarist.

Firms sometimes increase nominal output, at least in the short run, without increasing consumer welfare. Product misrepresentation or exploitation of behavioral biases are examples. A credit card company can emphasize an initial period of zero payments, while the later high payments are difficult for a consumer to understand; she enrolls or purchases more than if she had a better understanding. Ticket sellers can tack on fees at the end of the purchase process—before the consumer pays—and not lose sales; those same consumers choose not to buy when the fees are declared up front. A prominent example of the deviation between consumer welfare and (the court’s definition of) output occurred in the American Express case. The anti-steering rules at issue functioned like an MFN for the price of credit cards to the merchant. The AmEx rule stopped merchants steering transactions to cheaper cards, expanding AmEx output at their expense. But critically, no rival credit card could implement a strategy of low merchant prices, so they all responded by mimicking American Express’s supracompetitive fees. Those high fees then caused competition for cardholder usage with perks and points, which in turn encouraged card holders to overuse their cards. Those increased card fees became part of a merchant’s cost structure and had to be borne by all consumers in the form of higher prices (if no surcharging is possible, the good has the same price regardless of the form of payment). And of course, as economics teaches, those higher prices for retail goods necessarily caused lower output. The case shows that if a court considered only AmEx’s output, it would move against consumer welfare. Correctly tracing through the impact of the conduct on retail output would have led the court to the right conclusion and protected consumer welfare.

We try to limit these strategies with regulation, consumer protection, and product safety or information standards. When those tools do a good job, output returns to its role as a good proxy for consumer welfare. This is the setting antitrust law takes as given and must establish to avoid unworkable complexity. In complex or novel settings economists may need to do some work to model how consumer welfare relates to output. The output of interest is the total output in the market and not that of the defendants.

Focusing on output also helps to resolve the apparent conflict between the welfare of consumers, who prefer low prices, and workers, who want higher wages. Workers ordinarily benefit as the demand for labor increases, and labor demand usually rises or falls with changes in product demand. Witness what happened to the U.S. labor market as the country entered and then emerged from COVID-19 restrictions. Labor is mainly a variable cost, certainly in lower wage ranges. When the output of a product, say t-shirts or restaurant meals, decreases by 20%, labor usage decreases as well. Antitrust policy helps labor by ensuring that product output is competitive. To be sure, there may be additional ways to raise wages, such as workers sharing rents from economic regulation or market power. But a far more reliable source of income for an average worker is to be exposed to robust and strong demand for labor.

Do product market restraints that reduce the demand for labor always lower wages? Not if the labor market is perfectly competitive. In that case, wages remain unchanged as demand moves. But many labor markets exhibit at least some upward slope in the supply of labor, and some may exhibit a great deal. In that case a reduction in the output of labor can cause welfare losses just as a reduction in product demand does. We care about both the short- and long-run impact. If an anticompetitive reduction in the price paid for nurses or for video content lowers payments below competitive levels, workers will stop training to be nurses and investment in video content will fall. Output may not respond immediately, but consumers will be harmed in the long run.

So a workable tool for measuring consumer welfare is the effect of a challenged practice on output or price. In relatively few settings we may see a divergence between output and true consumer welfare, but these situations can be analyzed and typically controlled. Measurement issues are significant, but for nearly all purposes the measurements are ordinal, not cardinal. That is, we need to show that a practice tends to reduce output, but calculating an exact amount is unnecessary to make this point. The statutes do not require cardinal measures, other than the Clayton Act’s insistence that a lessening of competition be “substantial.” Cardinal measurement is not even necessary in private damages actions. A damages plaintiff need not show losses in welfare but rather private losses—typically either higher prices or lost business value in competitor suits. Indeed, the “deadweight loss,” which Bork identified with the welfare loss of monopoly, is not even recoverable by purchaser plaintiffs because there are no purchases in that range.

Antitrust alternatives to consumer welfare

What about alternatives? The two alternatives most commonly suggested today are that antitrust law should protect the “competitive process” or that it should target “bigness.”

The idea that antitrust should protect the “competitive process” has been voiced by some Supreme Court justices, as well as the current head of the Department of Justice Antitrust Division. Its strength is also its weakness: it does not provide any metric for measurement. As a result, liberals wishing to expand antitrust law and conservatives wishing to shrink it have both used a “competitive process” rationale. Justice Stephen Breyer used it to explain why American Express’ policy of forbidding merchants from switching buyers to a lower cost card violated the competitive process. He also used it to justify a telephone monopolist’s exclusive arrangement with a single provider. Justice John Paul Stevens used it to defend the rule forbidding maximum resale price maintenance, while Justice John Marshall Harlan II used it to attack that very rule. Some cases define “competitive process” by identifying it with consumer harm, thus pilfering the language of consumer welfare. Others have used it to exonerate conduct that they admitted caused consumer harm. Some have used it to explain why antitrust protects competition, not competitors. The enthusiasm for new vocabulary may be driven by the desire to change jurisprudence. Those observers who have concluded antitrust has been harmfully permissive in the last decades want to change outcomes, which may require a new word, even if it defines similar underlying concepts.

Opposition to “bigness” as an antitrust goal does not suffer from the same deficiencies. Like consumer welfare tests, it provides an identifiable goal, assuming we agree about how big is big. “Bigness” tests violate two fundamental principles of competition analysis, however. One is that market power attaches to products, not to firms. A second is that the target is not absolute size but rather size in relation to some market. For example, a one-store grocer in Crested Butte, Colorado, may have more market power in its market than Chrysler, even though Chrysler is thousands of times larger. Chrysler has several competitors while the isolated grocer does not. A policy directed at pure size is also unconcerned with differences between horizontal and vertical expansion. For example, when a firm acquires a $10 billion asset, it becomes bigger by that amount whether the acquired firm is a competitor (horizontal) or a supplier (vertical). As a result, concerns with size are not moored in competition policy. The Supreme Court has explicitly rejected “mere size” as a target of antitrust law.

“Bigness” is a poor predictor of low output and high prices, which are effects of monopoly. A large firm may inhabit a large market (e.g. cars) or be large because its products are popular with consumers (e.g. cars). But a policy against size is likely to protect higher cost or less innovative competitors, many of whom may be smaller. For example, the great anti-chain store movement of the 1920s and 1930s gave us the Robinson-Patman Act, which targeted firms owning four stores or more. Independently owned pharmacies have long sought protection from intense chain price competition with government regulation.

A focus on competitive output and price as an antitrust goal suggests several propositions, offered here as discussion points:

- While macroeconomics is not normally relevant to antitrust policy, certainly not in individual cases, overall productivity is important: as individual markets are more competitive and produce more, the economy as a whole usually benefits.

- A focus on industrial concentration, which has been voiced by the White House, is justified to the extent that higher concentration is associated with oligopoly, reduced innovation, lower output, or higher prices.

- A general policy of protecting higher cost or less innovative firms will harm both consumers and labor.

- The relentless pursuit of naked horizontal restraints is fully justified, while market mergers and vertical restraints require more analysis.

- The test for mergers should be whether a merger will lead to reduced output (or higher prices) in at least one market (relative to the but-for world); once a violation is found, the remedy of divestiture of illegally obtained assets should always be on the table.

- “Bright line” antitrust rules, such as per se condemnation of tying, maximum resale price maintenance, or cost reducing mergers or joint ventures harm both consumers and labor because they sometimes prohibit output-expanding activity.

- Antitrust should stick with its historical concern for poorly performing industries exhibiting rigid oligopolies, lack of innovation or new entry, or persistent monopoly.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.