In 1949, the innovative French economist and policymaker Jean Fourastié introduced a theory of growth and technological development that economists could still use today, as well as predictions regarding the future of economic development that proved to be quite prescient.

This article is part of ProMarket’s history series. You can read all of the pieces in the series here.

French economist and policymaker Jean Fourastié (1907-1990) introduced a theory in 1949 predicting the economic growth of the “Trente Glorieuses” (the Glorious Thirty years of post-WWII growth), the subsequent fall of manufacturing and rise of services, and a secular stagnation at the turn of the millennium.

Data-Based Economics

At the end of the Second World War, Fourastié joined Charles de Gaulle’s General Planning Commission to oversee the measurement of productivity in the French economy. Over the following decades, Fourastié remained involved in the various planning bodies that flourished in the French administration at the time. He always kept faith in market forces—but within a state-controlled framework.

Despite his position as an economics professor at Sciences-Po and the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, Fourastié kept away from debates on economic theory, claiming that the needs of the time were for applied economics. His scientific approach was the one of an empiricist: data led to theory. Through books, columns, and TV shows, Fourastié became a public figure who explained the deep changes the French economy was experiencing. He forged the term “Trente Glorieuses” (The Glorious Thirties), arguing that life in France was more shaken up by an “invisible” economic revolution due to the rapid increase in productivity, rather than France’s different political revolutions.

A Growth Theory Grounded on Technical Progress

For productivity measurement purposes, Fourastié’ constituted numerous series of prices expressed in number of unskilled hourly wage, a work still in progress. His observations inspired his theory of economic development, exposed in a book he published in 1949, Le Grand Espoir du XXème siècle (“The Great Hope of the Twentieth Century”). The Great Hope has not been translated to English but the mains concepts were presented in a book published in 1960 as The Causes of Wealth and are discussed in an article in History of Political Economy.

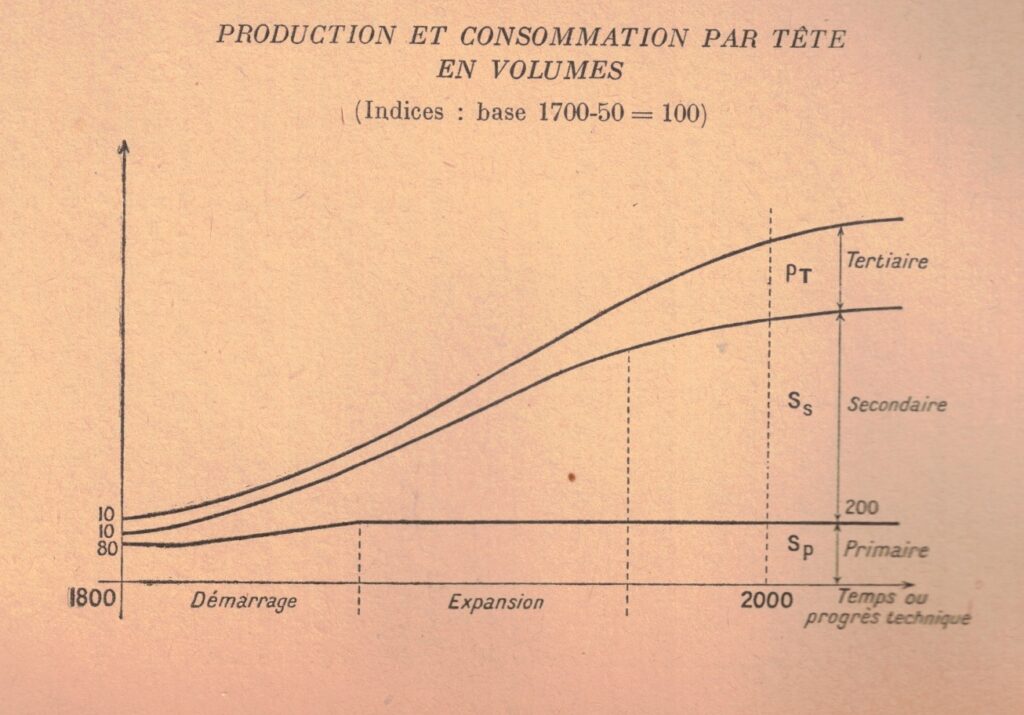

Technological progress is the key determinant in Fourastié’s theory of growth: “technological progress enables an increase in production by hours of work, but its effect is not homogeneous over industrial sectors and over time.” (Fourastié, 1949). Fourastié used this feature as a criterion to distinguish sectors: the primary sector consists of activities characterized by medium technological progress (mainly agriculture); the secondary sector, of activities with considerable technological progress (industry, for the most part); and the tertiary sector, of activities with low technical progress (mainly services).

Fourastié offers a striking example: in 1700, the cost of producing four square meters of mirrors (as in Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors) represented 40,000 hours of unskilled labor; this cost then dropped to 6,500 hours in 1850, 550 hours in 1900, and only 100 hours in 1950. Manufacturing mirrors has high productivity gains and is thus classified as part of the secondary sector. However, the cost of cleaning a mirror was one hour of unskilled labor under Louis XIV and has remained around this level ever since. Hence, cleaning activity, which exhibits approximately nil productivity gains, is classified in the tertiary sector.

Besides, the study of consumer behavior led Fourastié to assume “saturations” in the consumers’ demands for goods produced by the primary and secondary sectors. This idea of a cap on the demand for agricultural goods echoes Engel’s law, which states that as consumers’ income increases, the share spent on food decreases. In addition to a cap on food consumption, Fourastié expected that the demand for manufactured goods would also quickly reach a saturation level that could correspond to “two cars, three bathrooms, and two telephones per inhabitant, including children.”

Conversely, the demand for tertiary services can be thought of as endless because “services help to multiply time” for human beings. For Baumol, people tend to ask for more services rather than for additional manufactured goods precisely because human contact is somehow critical for welfare, and services are activities that often involve in-person contact. Owing to this, however, they are also much less sensitive to technological progress.

“Fourastié’s analysis enables us to reconcile the ongoing presence of technological progress with the low productivity gains we currently observe.”

Accurate Predictions

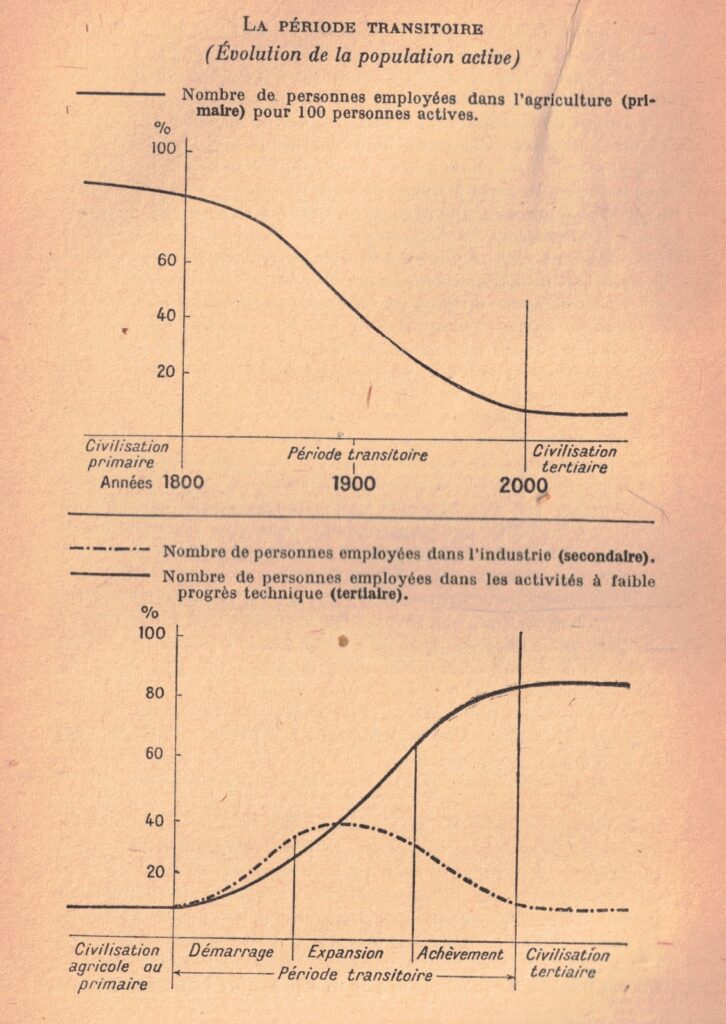

Once the saturation in demand for primary goods occurs, the ongoing productivity increase would lead to a fall in the workforce in the agricultural sector, seeing as there’s a limit to how much people can eat. Indeed, technical progress allows to maintain the required production while using fewer workers. Thus, an increasing share of the labor force would be available to work in other sectors, especially manufacturing.

A similar process of saturation will then quickly be observed in the secondary sector: the strong productivity gains in manufacturing would enable firms to meet the needs of consumers with fewer workers. For sure, this prediction was only a barely-discernible future for a 1949 Frenchman suffering from strict rationing of both food and manufactured products. Nonetheless, according to Fourastié, this future would most likely be marked by the fact that more and more workers would become available to work in the tertiary sector, in which the demand is never saturated.

Fourastié had forecast that about 80 percent of the population would eventually work in the tertiary sector. He believed the advent of this “service civilization” would occur around the year 2000, opening a new era of stability during which the labor force would work mainly in services, and would enjoy high standards of living. This, in Fourastié’s own words, was the “Great Hope of the twentieth century.” At a time when industry was triumphant, this prediction was highly original.

Fourastié summarizes the outcome of his theory as follows:

“The machine forces Man to specialize in the human (…) tertiary values invade economic life; therefore, one can argue that the civilization of technological progress will be a tertiary civilization—nothing will be less industrial than the civilization triggered by the industrial revolution.”

Fourastié’s theory explains that before the economic take-off (i.e., during the “primary civilization”), growth had been weak because the labor force was mainly working in agriculture. The high-growth regime observed between 1800 and 2000 could be considered a historical exception, which Fourastié attributes to the displacement of workers from low to high productivity activities triggered by technical progress. The peak of growth matched the period (“Expansion” on Fourastié’s graph) during which much of the labor force was working in the secondary sector, the sector experiencing the highest productivity gains. Beginning with the end of the 20th century, the largest share of the labor force is once again working in activities characterized by low sensitivity to technical progress—this time, mainly in services, and economic growth thus gradually weakened.

While for Robert J. Gordon, as for many economists, the succession of disparate phases of growth is undoubtedly explained by the diversity of the successive innovations that followed one another; Fourastié assumes that technological progress will potentially continue at a constant rhythm. Nevertheless, he argues that its effect on global productivity will decrease due to the reallocation of the labor force towards tertiary activities. In fact, Fourastié’s analysis enables us to reconcile the ongoing presence of technological progress with the low productivity gains we currently observe.

Fourastié offers several forecasts regarding our present. Continuous technical progress led the relative price of machines to decline, allowing Fourastié to forecast a concomitant fall in interest rates: “Obviously, we will need less and less financial capital; there will very probably be a trend towards a decrease in the cost of money because the demand for money will be smaller.” In fact, the secular stagnation currently seen by some observers in advanced economies is characterized by such low interest rates.

Fourastié also accurately predicted that:

“(…) farmlands will have lost almost all their value and industrial equipment will no longer be a hard-fought area for social struggles (…). However, tertiary goods (artwork, collections) or the generating of tertiary services (touristic and commercial locations, land pleasant to live on) will maintain all their prices.”

Influences and Prolongations

When personal services exhibit cost increases due to stagnant productivity, it is called “cost disease.” In a unified labor market, wages in the services sector are pushed up in response to rising salaries in activities that did enjoy productivity gains. As a result, the cost of personal services, such as medical care or education, would tend to increase relatively more than manufactured goods because only the production of the latter exhibit productivity gains. William Baumol formalized this phenomenon but repeatedly credited Fourastié as being the source of his analysis. In our 2018 paper, co-written with André Grimaud, we formalize the complete Fourastié theory.

Jean Fourastié, the civil servant and public figure, has accompanied the French toward the increase in living standards they enjoyed during the second part of the twentieth century. His thoughts on the changes and continuities of economic development enable contemporary economists to shed new light on the process of development since the first industrial revolution, as well as the possible path the global economy seems to be taking.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.