In an excerpt from their new book, Six Faces of Globalization: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why It Matters, Anthea Roberts and Nicolas Lamp draw on contemporary examples to illustrate the corporate power narrative about winners and losers of globalization.

An automobile factory in the United States or Canada closes. Production of the vehicle model in question is moved to a new plant in Mexico or China. This scenario has played out countless times over the past three decades. How should we make sense of what is happening?

For protectionists, the answer is clear. The factory closures are an unmitigated loss for the United States and Canada and a gain for Mexico and China, because the manufacturing jobs at issue are “good” jobs that yield a decent standard of living and are essential to sustain manufacturing communities. Proponents of the establishment narrative offer a different reading: the “really good” jobs—those in research and development, design, and marketing—are likely to stay in the developed country, and their number might even increase, as the company can broaden its product offering by dint of the more cost-effective production. In other words, workers in developed countries get to move up the two ends of the smile curve where their work creates more value added, resulting in higher profits for companies and higher wages for workers in these countries. Proponents of the establishment narrative acknowledge that short-term pain will ensue but claim that everyone will gain in the end: the Mexicans or Chinese will be able to get factory jobs, and the average productivity of workers in the United States and Canada will increase.

The corporate power narrative argues that both of these readings miss a crucial part of the story, since they ignore what happens to the jobs as they are moved from the developed countries to the developing countries. In the words of Canadian union leader Jerry Dias, international agreements such as NAFTA have allowed corporations to take “good Canadian jobs and [make] them bad ones in Mexico.” What was a well-paying union job with health insurance and a pension in Canada becomes a Mexican minimum-wage job without benefits. At the same time, corporations can use the threat of moving ever more jobs to Mexico to pressure Canadian and US workers to accept lower wages and inferior working conditions. As the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) has argued, NAFTA makes “it easier for global companies to suppress wages, disrupt union organizing, and skirt clean air and water obligations by relocating or threatening to relocate production elsewhere . . . [B]y providing incentives that make offshoring decisions more attractive (including [investor-state dispute settlement], guaranteed market access, excessive intellectual property protections and a low-standards regulatory framework), these deals provide added leverage for employers to actively hold down wages and standards by ‘predicting’ workplace closures and offshoring of jobs if workers form a union or refuse to give back hard-won wages and protections during negotiations.”

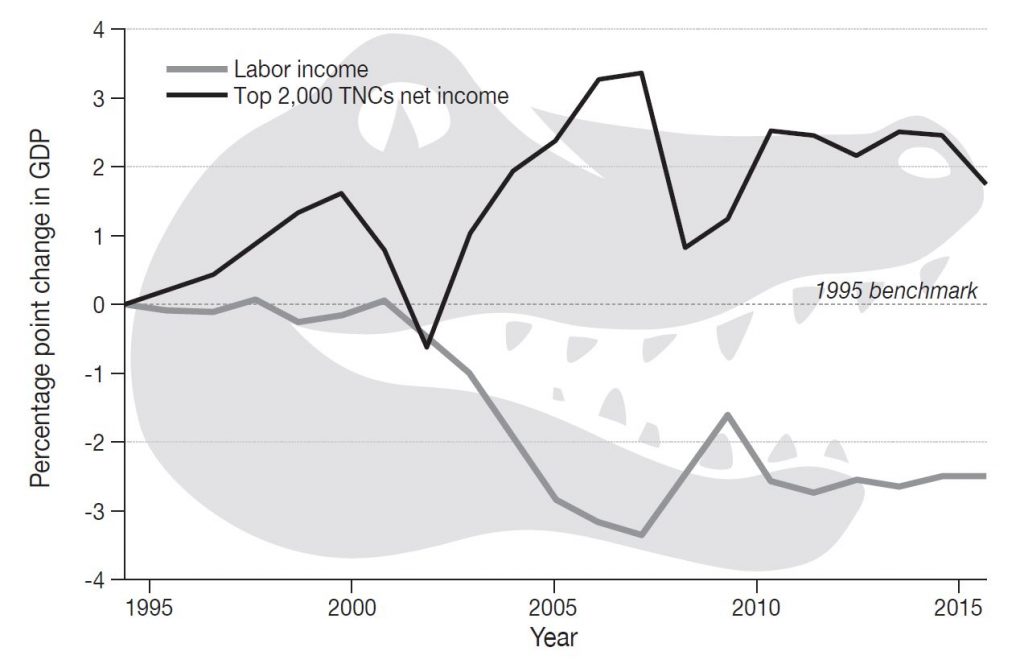

The corporate power narrative thus differs from both the establishment and the right-wing populist narratives in how it identifies the winners and losers from the offshoring of production: it holds that corporations and their owners win, and workers in both developed and developing countries lose. Along these lines, the AFL-CIO pointed out that, as a consequence of NAFTA “dragging down taxes, wages and standards towards their lowest level within the trade bloc,” the income distribution in all three NAFTA countries has “become more unequal as capital captures an ever-larger share and workers an ever-smaller share.” As a result, corporate profits have steadily increased and the labor share of income has concomitantly declined, which is reflected in the “crocodile curve” (Figure 6.2).

In contrast to the protectionist viewpoint, which pits workers in developing and developed countries against each other and attributes all outsourcing of jobs to “cheating” by developing countries, proponents of the corporate power narrative such as labor advocate Jeffrey Vogt concede that “developing countries should be able to attract investment based on a comparative wage advantage.” Yet the corporate power narrative also contradicts the establishment narrative’s contention that workers invariably win; rather, the narrative maintains that workers lose—both individually and collectively—whenever wages “are artificially low due to labor repression.” Dani Rodrik emphasizes the need to “distinguish cases where low wages in poor countries reflect low productivity from cases of genuine rights violations.” Violations of worker rights in developing countries concern the corporate power narrative not only because such violations affect the fate of the individuals involved but also because they can determine whether workers collectively gain from economic globalization. As the AFL-CIO has pointed out, “Rais[ing] the wages and protect[ing] fundamental rights for workers in Mexico” would help workers in all three NAFTA countries, since it would “limit … the ability of corporations and Mexico’s ruling elite to use Mexican wages as an instrument of labor arbitrage.” If workers in Mexico and other developing countries were able “to bargain collectively for better wages and working conditions, … the benefits of trade [would] accrue not only to capital but also to labor.”

It follows that for proponents of the corporate power narrative such as journalist William Greider, thinking about the winners and losers from economic globalization “does not begin by examining Americans’ own complaints about the global system. It begins by grasping what happens to people at the other end—the foreigners who inherit the American jobs,” since the misery of workers in developing countries is “the other end of the transmission belt eroding the structure of work and incomes in the United States.” That is why proponents of the corporate power narrative do not see the solution as closing the border. “The only plausible way that citizens can defend themselves and their nation against the forces of globalization is to link their own interests cooperatively with the interests of other peoples in other nations—that is, with the foreigners who are competitors for the jobs and production but who are also victimized by the system.”

To North American proponents of the corporate power narrative, Exhibit A for what happens when tariff reductions put workers in different countries in competition with each other without the same labor protections is the conditions in the maquiladoras that sprang up on the Mexican side of the border in the 1980s. Writing in the early 1990s, Greider described the slums of Ciudad Juárez as a “demented caricature” of sub urban life in America: the employees of US flagship companies, including General Electric, Ford, and General Motors, lived in “squatter villages,” subsisting on wages that did not pay for basic necessities. “With the noblesse oblige of the feudal padrone, some U.S. companies dole[d] out occasional despensa for their struggling employees—rations of flour, beans, rice, oil, sugar, salt—in lieu of a living wage.”

Instead of creating broad-based prosperity, on this account, the presence of US corporations in Mexico perpetuated misery. The working conditions were so deplorable that turnover among the employees was high and the often very young employees did not have an opportunity to acquire useful skills that would spill over into the economy at large. The corporations created an “enclave” economy that left no lasting prosperity before they decamped to places with even cheaper labor. As Nader sums it up, “The corporate-induced race to the bottom is a game that no country or community can win. There is always some place in the world that is a little worse off, where the living conditions are a little bit more wretched. …The game of countries bidding against each other causes a downward spiral.”

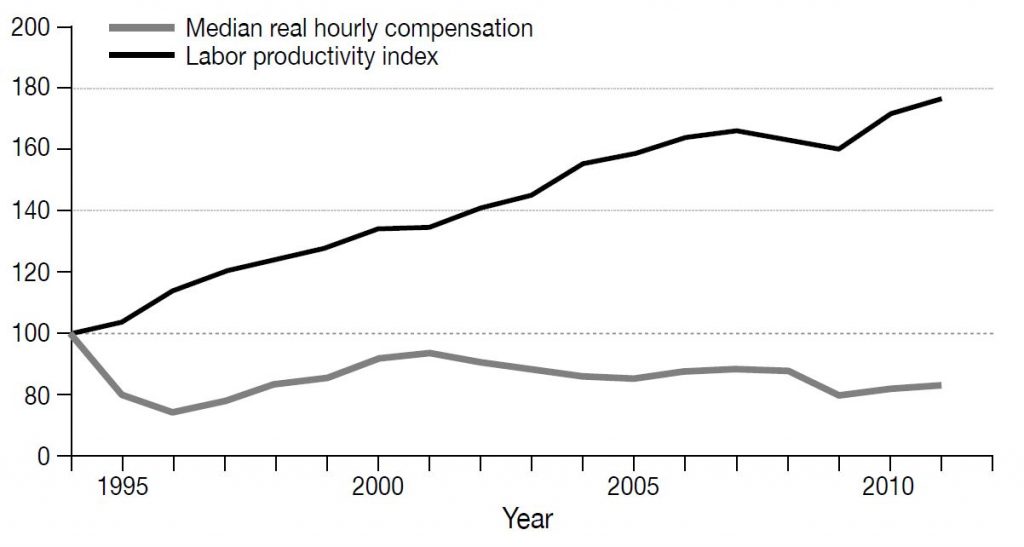

Proponents of the corporate power narrative argue that little has changed in the twenty-five years since NAFTA originally entered into force. The AFL-CIO points out that since the conclusion of NAFTA, “wages in Mexico have lost purchasing power, and the U.S.-Mexico wage gap actually has increased.” Mexican workers are far from being able to afford the standard of living that US workers whose jobs the Mexican workers inherited used to have. Dias frequently notes that Mexican workers cannot afford the cars they produce even though Mexican manufacturing productivity has been rising rapidly: between 1994 and 2011, productivity increased by almost 80 percent, whereas real hourly compensation fell by 17 percent (Figure 6.3). These statistics mean that despite “producing more, millions of Mexican workers are earning less than they did three decades ago.” The increasing gap between productivity and wages is the basis for the corporate power narrative’s claim that workers in developing countries are not really “winning”: these workers are not fairly rewarded for their work. Instead, the corporations that employ them are the ones that come out ahead, as they are able to appropriate a greater share of the gains from trade at the expense of both the Canadian and US workers who have lost their jobs and the Mexican workers whose wages do not reflect their rapidly rising productivity and barely allow them to subsist.

As NAFTA was being renegotiated in 2017 and 2018, Dias traveled to Mexico to put into action this insight into the interlinked fate of workers in developed and developing countries. Speaking into a bullhorn at a large protest in Mexico City, he conveyed a message of worker solidarity: “We all stand together, because the corporations only care about their profits, they don’t care about us. They take more and more and more, and we have less and less and less. They’re driving down the standards of workers in Canada, the United States and Mexico. So our strength has to be our unity. … They try to exploit workers. They pit workers against workers in each of our three countries. … Canadian and American workers know that our fight is not with Mexican workers. Our collective fight is with the governments, the international corporations.”

Excerpted from Six Faces of Globalization: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why It Matters, by Anthea Roberts and Nicolas Lamp, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.