Mandated legislation of worker representation is unlikely to be the magic bullet some policy-makers have pictured. A new paper finds workers may benefit from being employed in firms with worker representation, but these benefits reflect that these firms are likely to be larger and unionized and are not caused by worker representation per se.

Many western economies have experienced significant declines in the share of corporate income accruing to workers. In response, worker representation on corporate boards has gained momentum as a way to ensure the interests and views of the workers. Recent polls suggest that a majority of American voters want workers to hold seats on corporate boards. And leading politicians on both sides of the political spectrum in the US and UK are advocating a system of shared governance. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) proposed a federal bill in 2018 that would give workers in large corporations the right to elect two-fifths of all board members. In the UK, former prime minister Theresa May pledged to have workers represented on corporate boards in her campaign for the 2016 Conservative Party leadership election.

In our analysis, we first show that workers in firms with worker representation do see some benefits: New employees at a firm with worker representation are paid more on average, and wages of existing employees are less tied to firm performance, meaning they are less likely to suffer due to adverse shocks to their employers. But these effects are not due to worker representation per se. Conditional on the firm’s size and unionization rate, we find that worker representation has little, if any, effect. We therefore conclude that, despite the wide-spread enthusiasm, mandating worker representation is unlikely to benefit workers.

We study whether workers benefit from being represented on corporate boards in the context of Norway, using a unique matched panel dataset of all workers, firms, and boards covering the period 2004-2014. Using this dataset, we can measure the worker representation of firms and follow the earnings trajectories of workers over time, even if they switch firms.

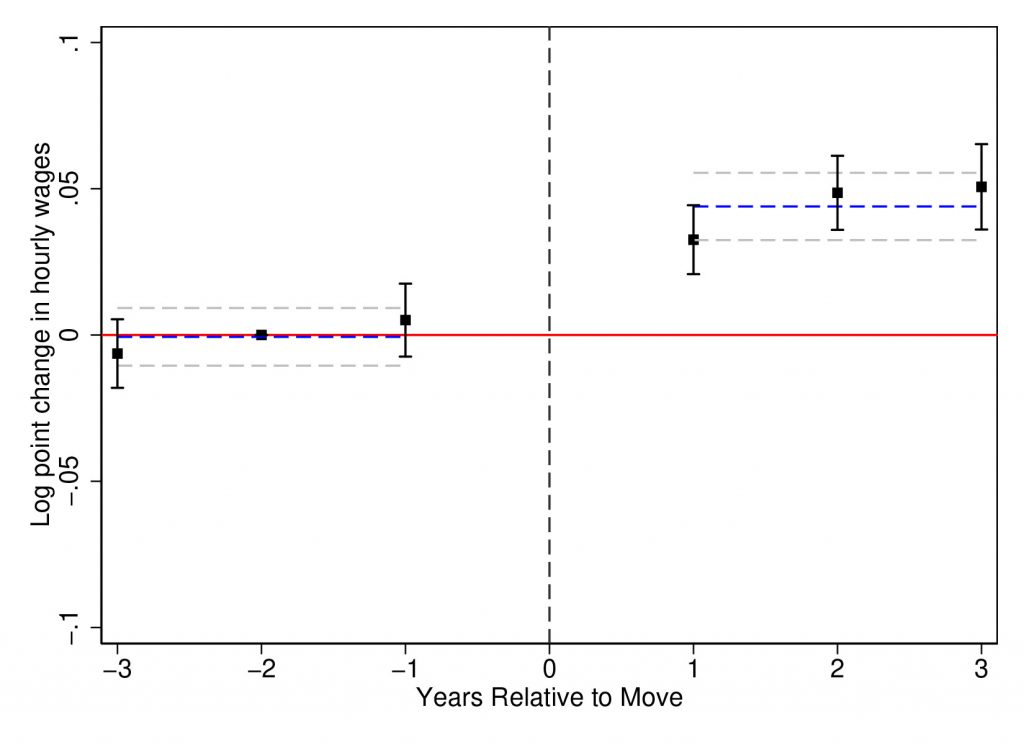

New employees in firms with worker representation earn more than in their previous job. But one might be concerned that the observed pay raise is influenced by adverse events occurring prior to the move. For instance, a decline in sales might simultaneously lead to pay cuts for existing employees while motivating workers to apply for jobs at firms with worker representation where job security might be higher. This could artificially depress their pre-switch earnings, making the wage impact appear to be greater than it actually is. To address this issue, we use co-workers moving from the same firm as a comparison group. Co-workers in the same firm are likely to experience similar events before switching jobs. In the years after the move, differences in wages between the two groups can therefore be attributed to worker representation on the board.

Figure 1a illustrates our first key finding: Workers moving into a firm with worker representation experience a 4 percent increase in wages, compared with their former co-workers moving between firms without representation.

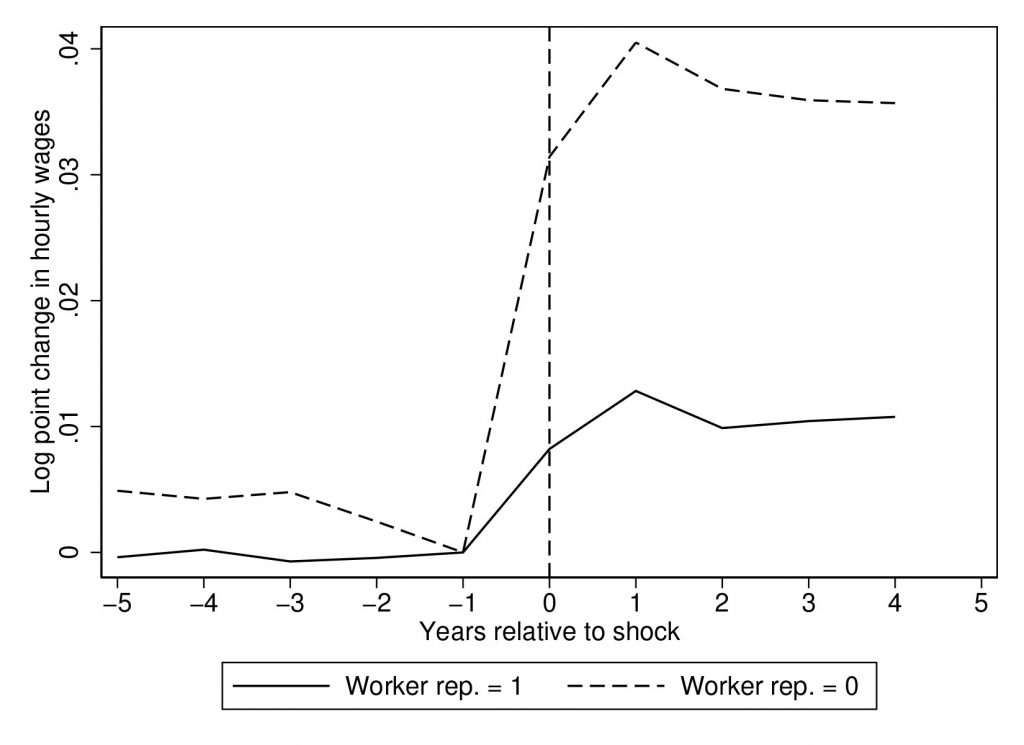

Figure 1: Wage impacts of being employed in a firm with worker representation

Not only do workers in firms with worker representation earn more on average, they are also better protected from fluctuations in firm performance. When wages are closely tied to the performance of the firm, workers may face dire consequences in the face of an adverse event such as a fall in the demand for the firm’s products. Figure 1b illustrates what happens to wages when a firm experiences a shock to its performance: In response to a 10 percent fall in the value added (revenue net of cost of materials) of the firm, the wages of workers decrease by 0.9 percent in firms without representation, while the wages of workers in firms with worker representation only decrease by 0.2 percent.

Still, these effects cannot be used to draw conclusions about the effects of a policy mandating worker representation. Worker representation is not randomly allocated to corporate boards, but likely driven by factors that might also affect pay. As a consequence, firms with worker representation are very different from firms without.

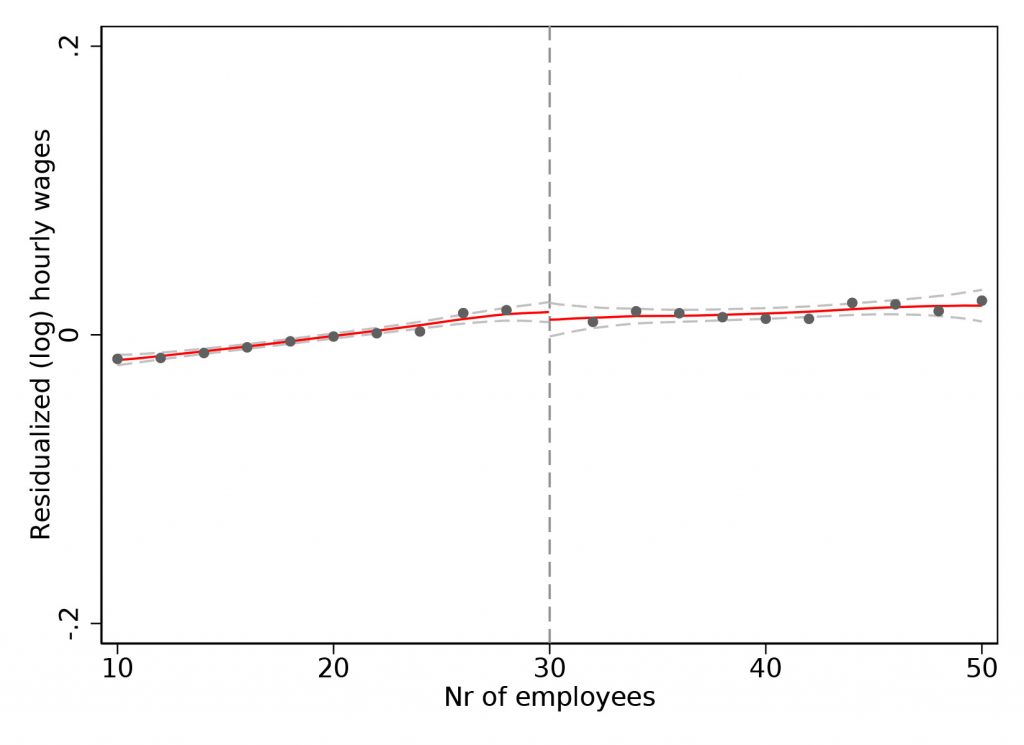

To shed light on the likely effects of a policy mandating worker representation, we first make use of a law that gives different rights to representation to workers in otherwise similar firms. In Norway, workers can demand worker representation on the corporate board if the firm has more than 30 employees. If introducing worker representation on a given board increased wages, we would expect to see a discontinuous increase in wages when firms become eligible by law. However, Figure 2a shows that there is no such discontinuity. Workers in firms that are only just eligible with between 30 and 40 employees do not earn significantly more than workers in firms that are barely ineligible with between 20 and 30 employees.

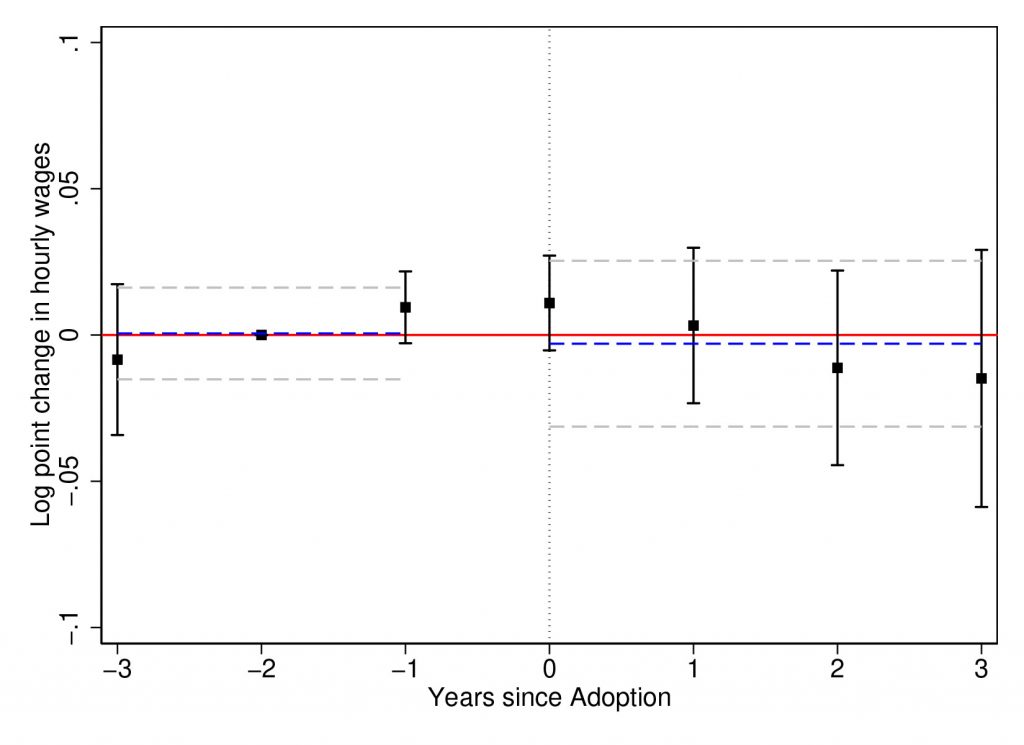

An alternative way of learning about the effect of introducing worker representation on the board of a given firm is to study the compensation of workers in firms that adopt worker representation in different years. The exact timing of adoption of worker representation is plausibly unrelated to other factors determining how much workers are paid. Any differential change in wages for workers in firms that adopt worker representation in different years can therefore be attributed to the workers being represented on the corporate board. However, as Figure 2b shows, we find no evidence of a significant change in pay for existing employees in the years after their employer adopts worker representation, compared to workers in firms that adopt worker representation in later years.

Figure 2: Effects of adopting worker representation on wages

Even though employees do benefit from working in a firm with worker representation, we find that these gains are not driven by worker representation per se, but rather by other factors. Firms with worker representation stand out as considerably larger and more unionized than firms without representation. We show that the wage gains and improved protection from fluctuations in firm performance associated with working in a firm with worker representation can be entirely explained by differences in firm size and the share of unionized workers between firms with and without representation.

Our paper highlights that where you work matters for how much you make. Workers in firms with worker representation earn more and are better protected from adverse shocks to their employer. However, mandated legislation of worker representation is unlikely to be the magic bullet some policy-makers have pictured.