A company’s purpose is a core aspect of the organization: it influences the financial performance of company, and relates to its ownership characteristics, compensation policies, and strategy.

Editor’s note: This piece is adapted from a speech presented during a 2020 conference on corporate governance and purpose, organized by the IESE Center for Corporate Governance and the European Corporate Governance Institute.

Corporate purpose has been a topic of discussion for nearly a century, beginning with early social scientists such as Adolf Berle, Gardiner Means, and Chester Barnard, who wrestled with the roles of both leaders in companies and companies in broader society. Today, the topic has taken on a renewed urgency as large societal challenges—reduced social mobility, climate change, distrust in media and institutions—loom. Companies have been simultaneously implicated in these challenges and looked upon for solutions. But what precisely is corporate purpose, and how does it relate to what we know about firms today?

Nearly every company has a “purpose” or “mission” statement. Most of these statements have a social focus. Microsoft’s is “to empower every person and every organization on this planet to achieve more.” John Deere’s is “to improve the quality of life for people around the world through our commitment to serving those linked to the land.” WeWork’s is the lofty “to create a world where people work to make a life, not just a living.” While some of these statements reflect deep truths that undergird organizations, many others are just nonsense. From the outside, it is very hard to tell the difference as Luigi Guiso, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales found in their 2015 paper, “The Value of Corporate Culture.” This “cheap talk” nature of corporate purpose renders it a challenging topic to study. Purpose is hard to define, hard to measure, and hard to isolate from other aspects of a company.

Seven years ago, my collaborators and I embarked on a research program to provide empirical evidence on corporate purpose and firms. We provide a measure of corporate purpose that does not depend on official statements but instead is based on actual employee beliefs. What we have found is that a company’s purpose is a core aspect of the organization: it influences the financial performance of company, and relates to its ownership characteristics, compensation policies, and strategy.

We define corporate purpose as “the set of beliefs about the meaning of a firm’s work beyond quantitative measures of financial performance.” Purpose provides both an “outside-in” and an “inside-out” function for firms. The “outside-in” function is to communicate to external parties what role the firm can be expected to play in broader market and society. In that sense, purpose can be seen as a reputational device, enabling outsiders to make sense of the rationales behind corporate actions absent direct access to the leadership suite. It also differentiates the companies for its customers: when choosing to deal with the firm, customers are also choosing to support the purpose of the organization.

“In its internal capacity, corporate purpose enables a shared sense of meaning among members of the organization.”

While outside parties are important, the inside-out nature of purpose is arguably its more vital function. In its internal capacity, corporate purpose enables a shared sense of meaning among members of the organization. We have long known from research in social psychology—such as Viktor E. Frankl’s 1963 book Man’s Search For Meaning—that we are meaning-motivated beings, with this motivation coexisting with and at times supplanting the need for material rewards. Since Frankl’s work, a deep body of work has demonstrated the centrality of meaning, with people working harder and at a higher level when they find meaning in their endeavors (such as here and here) and selecting into different jobs and organizations. Corporate purpose provides the organizational analog of this idea, addressing the following question for employees: what is the greater meaning of our collective endeavor?

This purpose is intangible and cannot be measured directly. To study it, we need to avoid the cheap talk that is endemic in formal purpose statements. Instead, we infer the strength of corporate purpose using the following logic: firms with employees that, on aggregate, have a strong sense of meaning in their work are those that have implemented a compelling corporate purpose. We measure purpose using a large survey by the Great Place to Work Institute (GPTW), the organization that administers Fortune Magazine’s 100 Best Companies to Work For annual list. As part of the application process, companies must administer a GPTW survey to their employees that covers various aspects of the workplace, including perceptions of management, coworkers, and the job. We analyze the raw survey results of all companies that applied to be listed in Fortune between 2006 and 2017, which includes more than 1.5 million employees and 1000 companies.

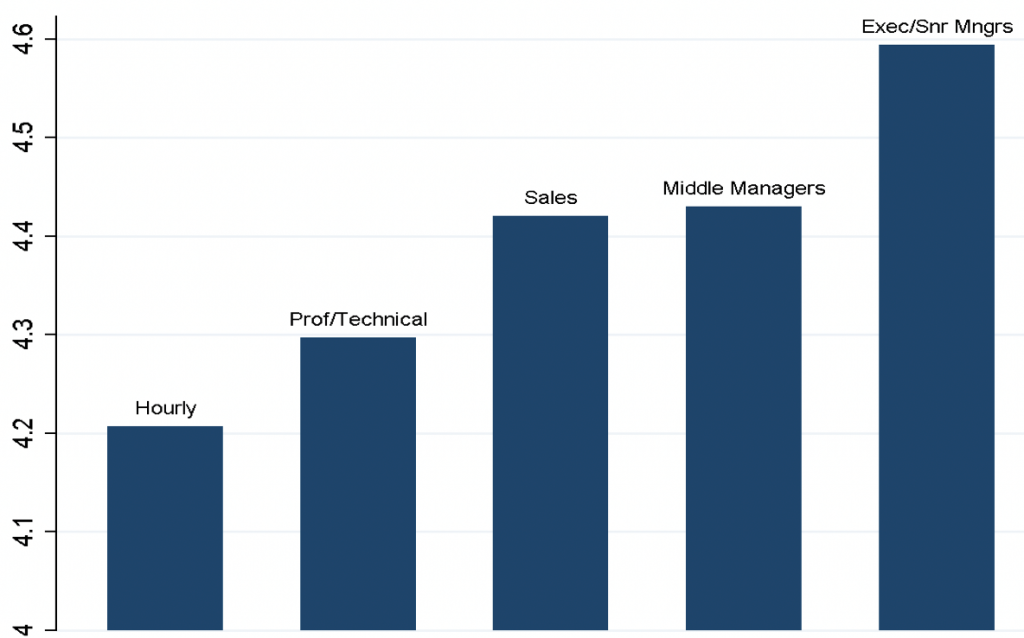

We have several studies so far that have examined various aspects of purpose, including financial performance, corporate ownership, acquisitions, and sustainability. Several patterns have emerged from this work. First, purpose falls down the hierarchy: the lower a worker is in the corporate hierarchy, the weaker his or her sense of purpose.

Second, across our studies, we have consistently found two types of purpose-driven organizations. One type is what we call high purpose-camaraderie organizations. These are organizations in which employees find high meaning in their work coupled with a strong sense of community within the company. The second type is what we call high purpose-clarity organizations, companies in which meaning is coupled with clear direction from management that links the top of the organization to the employee. Neither purpose alone nor purpose-camaraderie predicts stronger financial performance, but purpose-clarity does. Moving from the bottom to top decile of purpose-clarity for firms translates to about a four percent increase in return on assets. The stock returns of firms in the top quintile of purpose-clarity outperform the market benchmark by about seven percent per year. These are substantial effects.

Furthermore, this connection between purpose and performance is driven entirely by the middle ranks of the company: only when these middle ranks feel a high sense of purpose-clarity do companies outperform. These patterns appear causal; that is, purpose-clarity leads to stronger performance, and not the other way around.

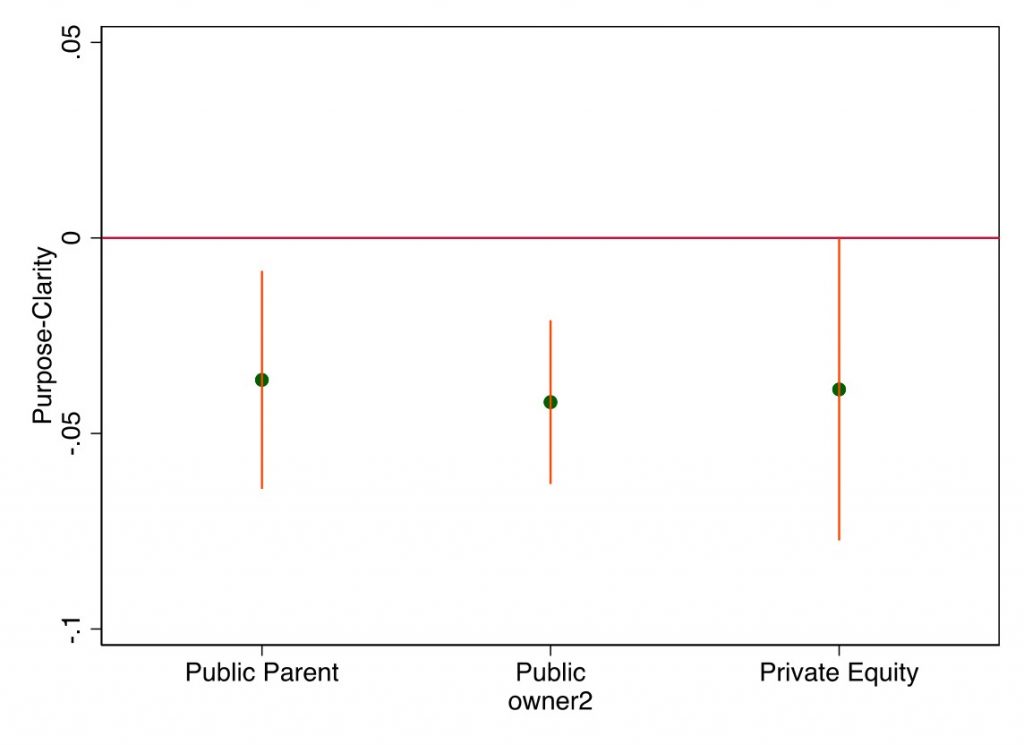

We have also examined how purpose-clarity varies across public and private firms. The red line in the figure below represents traditional private companies (that is, companies not owned by private equity firms). Compared to this baseline, purpose-clarity is markedly lower in public and private equity-owned companies.

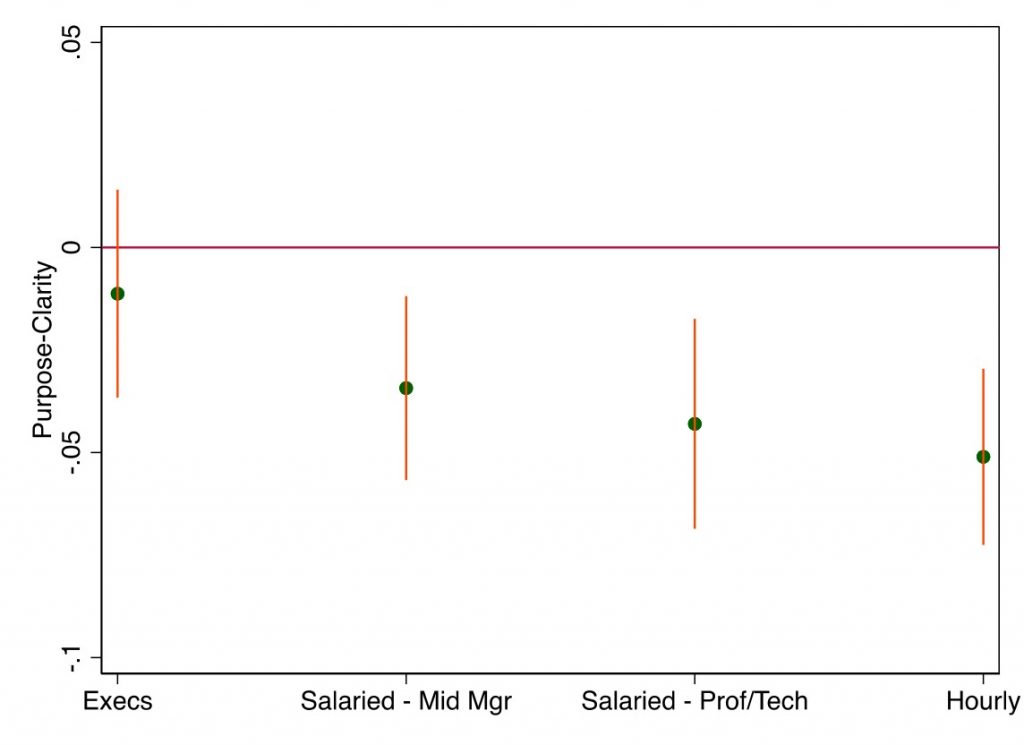

This difference between public and private firms is driven by employees down the ranks of organizations. This next figure shows this pattern. On the left-hand side is executives, then salaried middle managers, then the salaried professional ranks, and then hourly workers on the right of the figure. Another way to interpret this finding is that purpose-clarity weakens down the hierarchy in public but not in private companies.

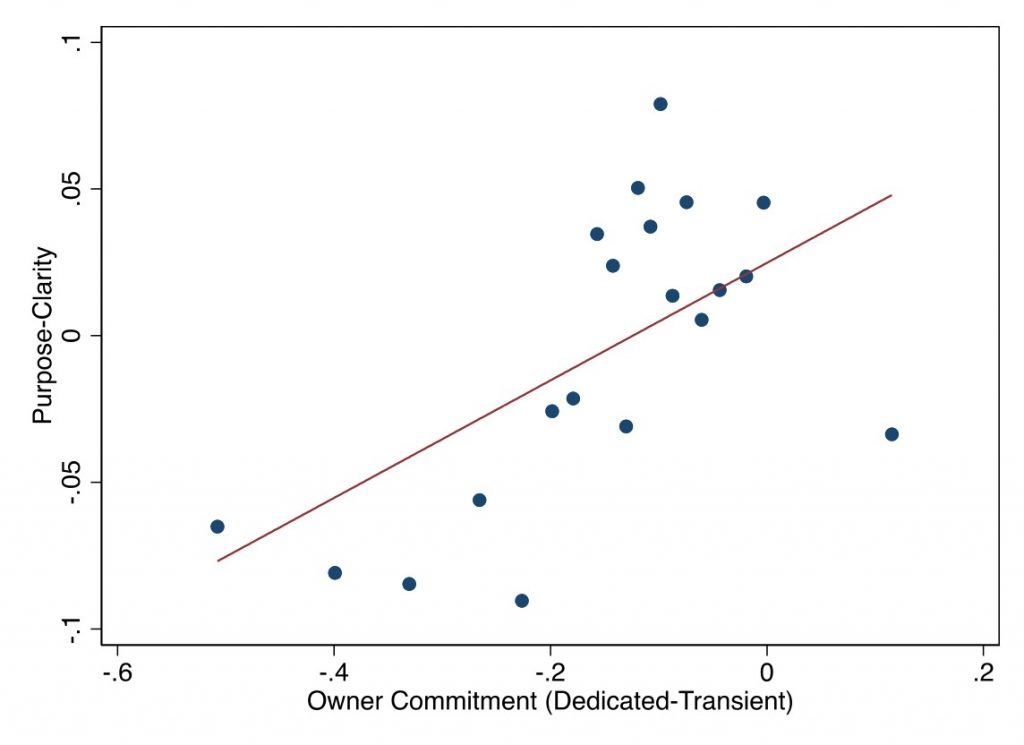

What is driving this difference between public and private companies? It appears that this difference is due, at least in part, to differences in commitment levels in corporate owners. To understand this effect, we examine how differences in shareholder commitment levels across public companies explains differences in purpose-clarity. We measure the degree of shareholder commitment by the relative share of dedicated and transient investors, and find that commitment and purpose-clarity are strongly related. In other words, firms with more committed shareholders are also those with a stronger sense of purpose-clarity, particularly among lower-ranked employees.

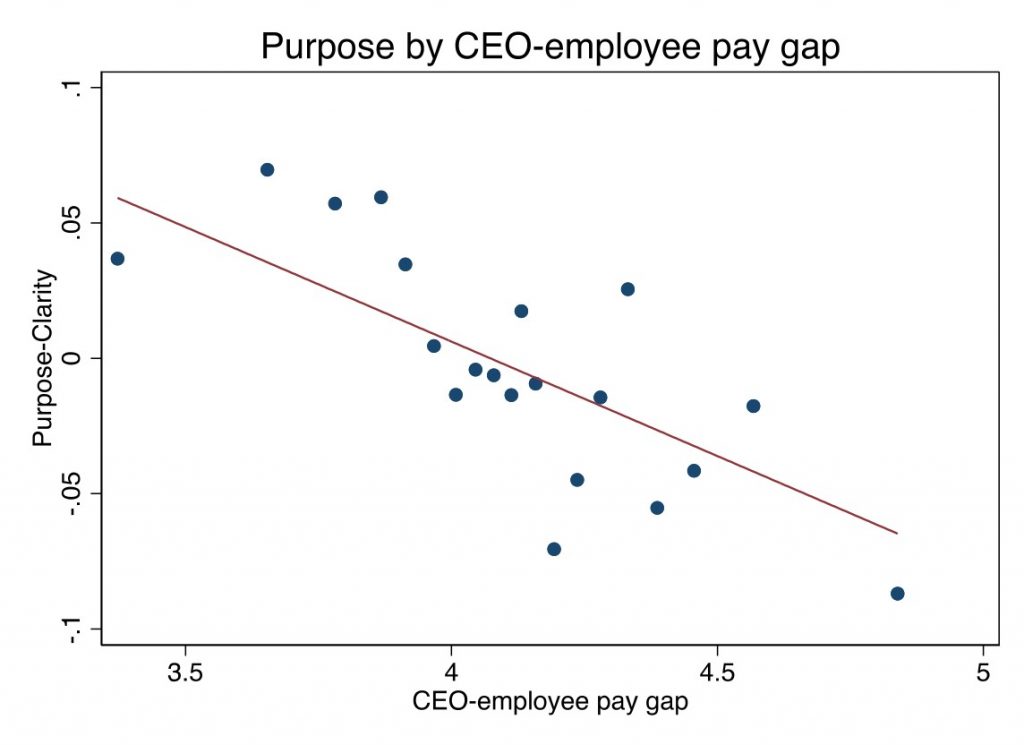

What do these firms do differently? They choose fewer outsider CEOs, engage in fewer mergers and acquisitions, and structure compensation differently. To illustrate this latter point, we find a strong connection between the pay gap between the CEO and salaried employees and corporate purpose. Firms with larger pay gaps have weaker purpose-clarity.

The role and importance of corporate purpose is one of the longest-running discussions in management and corporate finance. Can you motivate employees using larger, often social, aspirations or will that dilute their focus and confuse them? Should financial performance be a sufficient benchmark on its own or should it be supplemented with a more transcendent aim for an enterprise? Ultimately, why and for whom does the company exist in the first place?

These are questions that have generally been approached from a rhetorical perspective, with compelling arguments on both sides, but little evidence. Our research aims to inform this discussion with empirical facts. Corporate purpose and profits can be complements, a fact that runs counter to the assertion that we must choose between performance and social goals. Corporate purpose and shareholder commitment are also complements, a fact that is increasingly salient given that the average holding period for public shareholders is less than nine months and getting shorter.

References

- Berle, A. and Means, G. “Private property and the modern corporation.” New York: Macmillan. (1932).

- Bushee, B.J., 1998. The influence of institutional investors on myopic R&D investment behavior. Accounting review, pp.305-333.

- Barnard, C.I., 1938. The Functions of the Executive. Harvard university press.

- Edmans, A., 2020. Grow the Pie: How Great Companies Deliver Both Purpose and Profit. Cambridge University Press.

- Frankl, V.E., 1963. Man’s Search for Meaning. Simon and Schuster.

- Gartenberg, C.M., Prat, A. and Serafeim, G. “Corporate purpose and financial performance.” Organization Science, 30 no. 1 (2019): 1-18.

- Gartenberg, C.M., and Serafeim, G. “Corporate purpose in public and private firms.” (2021) working paper.

- Gartenberg, C.M., and Yiu, S. “Corporate purpose and acquisitions.” (2021) working paper.

- Gartenberg, C.M. “Purpose-driven firms and sustainability.” (2021) working paper.

- Guiso, L, Sapienza P, and Zingales L. “The value of corporate culture.” Journal of Financial Economics 117, no. 1 (2015): 60-76.

- Henderson, R., 2020. Innovation in the 21st Century: Architectural Change, Purpose, and the Challenges of Our Time. Management Science.

- Mayer, C., 2020. The Future of the Corporation and the Economics of Purpose. Journal of Management Studies