In addition to the challenges involved in manufacturing and distributing the new Covid vaccine from Pfizer, the reluctance of many Americans to take a Covid-19 vaccine, if and when one is available, remains particularly daunting.

Last Monday, November 9th, brought welcome news from Pfizer about the successful Phase 3 trial of what appears to be a 90 percent effective Covid-19 vaccine. Stock markets reacted with elation, ready to declare the Covid-19 crisis over.

Challenges lie ahead, of course. There is the challenge of manufacturing the vaccine, which will have to be applied in two doses. Then there is the further challenge of distributing it—a task that is especially demanding insofar as it will have to be refrigerated while in transit and storage.

Yet the most difficult challenge may actually be to get people to take it. A Pew Research Center survey of more than 10,000 Americans, administered last September, showed that no more than a slim majority (51 percent) of adult respondents would definitely or probably get a vaccine to prevent Covid-19, were it available today. The share of those who would definitely take a vaccine barely made up a fifth of the total (21 percent).

If take-up is that limited, the miracle cure may be no cure at all. It is worth recalling that immunity against measles requires 95 percent of a population to be vaccinated, while the comparable ratio for polio is some 80 percent. Given the highly contagious nature of Covid-19, containing it may require meeting comparably high thresholds.

What share of the population must be vaccinated in order to prevent the infected from spreading the disease depends not only on the properties of the virus, but also on behaviors such as mask-wearing and social distancing and on whether these persist into the post-vaccine period. Casual observation of the extent of “lockdown fatigue” suggests that these other contagion-mitigating behaviors may not persist. Some people may take the prospect of a vaccine at some future date as a license to go back to social business as usual today. That prospect would be alarming.

“Some people may take the prospect of a vaccine at some future date as a license to go back to social business as usual today. That prospect would be alarming.”

Transparency about risks to safety, if any, and consistent messaging by public health experts may help with take-up, as we discuss in a recent paper. But the patterns revealed by the September Pew survey, and by a companion survey administered five months earlier, do not suggest that opinions are especially malleable. In the US, Republicans are consistently less likely than Democrats to say that they would definitely or probably get a vaccine, and we know that party affiliation is relatively static. Individuals with a high school education or less are less likely to respond positively than those with college or post-college education. African Americans are less likely than other groups to indicate a willingness to take a vaccine, understandably given their troubled history with the US health care system (the Tuskegee Syphilis Study for example; see Alsan and Wanamaker 2016).

In addition, reluctance to take a vaccine may be Covid-19 specific. Messaging by certain politicians that Covid-19 is not a serious health threat—and in some cases, even questioning whether the threat exists—may cause people who support those politicians’ other policies to question whether a vaccine is necessary or effective. The perception of political interference with trials and regulatory approval, specifically in the context of Covid-19, may foster doubts about safety. When the Wellcome Trust surveyed Americans in 2018—pre-Covid-19—about whether vaccines were safe and effective, 77 and 87 percent of respondents responded positively—higher figures than returned by the Pew Research Center in the midst of the current pandemic. (Fully 77 percent of respondents to the Pew survey were somewhat or very worried that a vaccine would be approved and used before its safety and effectiveness was fully understood.)

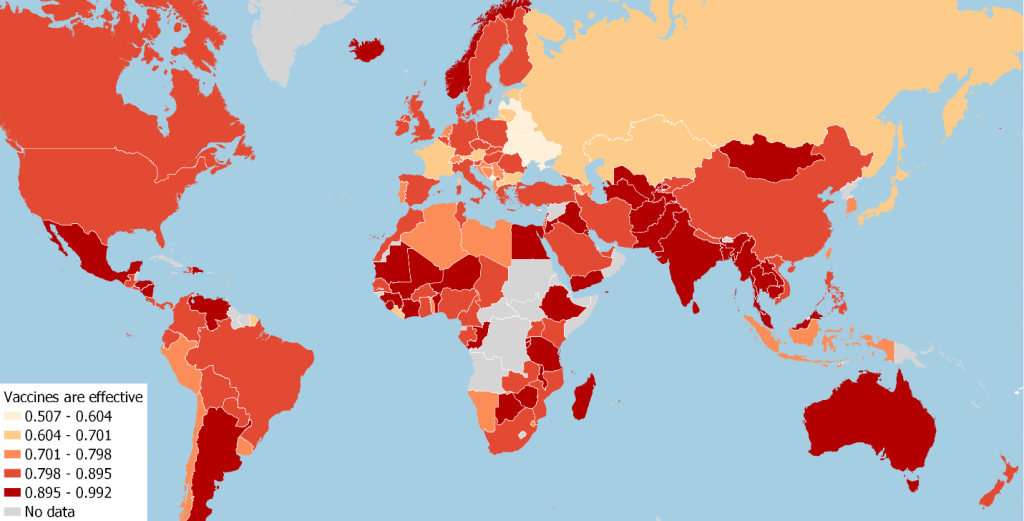

Figures 1 and 2, based on this 2018 Wellcome Trust study, show that vaccine skepticism is even greater in a number of other countries, most notably in Russia, in France, and in a surprising number of other Western European nations. What explains these cross-country patterns is far from clear but urgent to understand.

Our own analysis of the Wellcome Trust data suggests that vaccine skepticism is greatest among individuals who experience a pandemic first hand (in their country of residence) and specifically when they are in their “impressionable years” aged 18 to 25. This “experience” or “exposure” effect plausibly explains the difference between the earlier Wellcome Trust results for the US and the more negative Pew Research Center responses in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, with relatively few Americans having had pandemic exposure prior to the current year.

We further find that the negative revision of attitudes toward the safety and effectiveness of vaccines is limited to democratic countries, where citizens expect governments to be responsive to the public health emergency. In line with this interpretation, it is also driven by those individuals who experience epidemics under weak governments, where policymakers are less capable of mounting an effective public policy response. The experience of the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic is not far from fitting both of these two criteria.

This last finding also provides a ray of hope, however. A more consistent and effective public policy response, in which the governments’ non-pharmaceutical interventions produce positive results, may in turn foster confidence in the safety and efficacy of any vaccine they endorse and distribute. We can only hope.

References

- Aksoy, Cevat, Barry Eichengreen and Orkun Saka (2020), “The Political Scar of Epidemics,” NBER Working Paper no.27401 (June).

- Eichengreen, Barry, Cevat Aksoy and Orkun Saka (2020), “Revenge of the Experts: Will COVID-19 Renew or Diminish Public Trust in Science,” CEPR Discussion Paper no. 15447 (November).

- Alsan, Marcella and Marianne Wanamaker (2016), “Tuskegee and the Health of Black Men,” NBER Working Paper no.22323 (June).

- Pew Research Center (2020), “U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether to Get COVID-19 Vaccine,” Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center (17 September).

- Wellcome Trust (2018), Wellcome Global Monitor 2018, London: Wellcome Trust.

- WHO (2020), “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Herd Immunity, Lockdowns and COVID-19,” Geneva: WHO (15 October).