The Covid-19 pandemic has decimated livelihoods in developing nations, and coronavirus-related deaths are rising in Africa and South Asia at an alarming rate. How should developing countries combat the spread of Covid-19? A new study suggests that age-dependent lockdowns would be able to slow the spread of the disease in low-income countries while minimizing economic decline.

The developing world was largely spared from the initial wave of the pandemic. As health systems were brought to their knees in countries like Italy and Spain back in March, Africans and Indians watched nervously from the sidelines, knowing that their time would soon come.

That time, unfortunately, seems to be now. While official death counts from the novel coronavirus are still low in Africa and South Asia, they are rising at an alarming rate, and the lack of proper death records means that Covid-19 deaths are almost certainly greatly under-reported. Latin American countries are generally better at counting fatalities, and the statistics coming from countries like Brazil and Peru are grim, to put it mildly. Brazil lags only behind the United States in total cases and is on track to pass its northern neighbor.

Recent evidence on how the pandemic has decimated livelihoods in developing nations also makes for depressing reading. The World Bank estimates that between 26 and 58 million people in Africa will be pushed into extreme poverty, defined as incomes below $1.90 per day at Purchasing Power Parity. Africa’s per capita income, which was expected to rise by 1 percent before the pandemic, is now expected to fall by between 3 and 5 percent (World Bank, 2020)

How should developing countries combat the spread of Covid-19? To what extent should they try to prioritize the economic well-being of their vulnerable citizens over trying to reduce fatalities? What form should lockdowns take in order to make the best of this awful situation?

These are the questions we take up in our recent working paper. Of course, every country is different, and there are countless features that make developing countries different—even on average—from richer economies.

Yet some features are more important than others. We focus on four specific characteristics that differ between developing and advanced economies that are relevant for pandemic responses.

The first is that developing countries tend to have woefully inadequate health care systems, and the horror stories about some African nations having just a handful of respirators in the whole country are largely true.

The second is the limited ability of governments to dole out cash to citizens (let alone automatic bank transfers), due to insufficient ability to collect taxes.

The third, which is clearly related to the first two, is the large informal sectors that characterize virtually every low-income country. All three of these point in the direction of lockdowns being harder to enforce and less effective at halting the spread of the coronavirus.

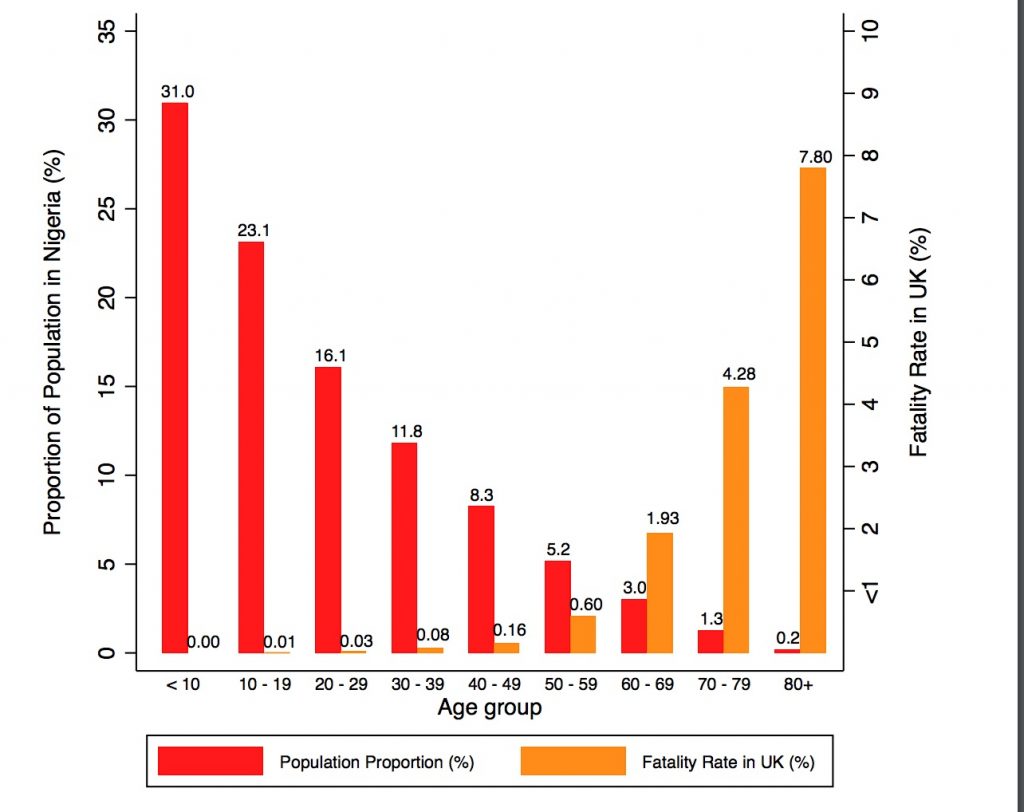

The fourth characteristic on which we focus is the one that bodes favorably for developing countries: their incredibly young populations. Figure 1 illustrates this feature by plotting the population distribution in Nigeria—Africa’s most populous nation (red bars)—against the death rates from Covid-19 by age group (orange bars, Lancet cite, estimated for the UK).

A whopping 31 percent of the Nigerian population are below age ten, and another 23 percent are between 10 and 19 years old. Death rates for these two groups are below 0.01 percent—meaning 1 death for every 10,000 infections. In other words, more than half of Nigeria’s population faces a very remote chance of dying from the virus if they become infected.

Of course, this assumes that Nigerians face the death rates by age of the United Kingdom, which is unlikely. Nigerians of all ages have more underlying health troubles, on average, than residents of the UK, and health facilities are less effective in Nigeria. Yet the differential death rate by age seems not to be mostly about hospital care, but rather biology, as the virus seems much less capable of infecting and impacting the young.

The flip side is that death rates for the elderly—the most vulnerable group by all accounts—are likely to be higher in Nigeria than they are in the United Kingdom. So the 7.8 percent death rate pictured in Figure 1 for those aged 80-plus is likely to be an underestimate of the actual death rate in Nigeria. However, only 0.2 percent of Nigerians are actually over the age of 80, which again signals just how powerful differences in the age distribution are for the potential health impacts of the pandemic.

Blanket Lockdowns: Advanced vs Developing Economies

In our paper, we simulate the effects of lockdowns of various types using a workhorse macroeconomic model with heterogeneous agents facing idiosyncratic risk and incomplete asset and insurance markets.

Like in other models of this sort, agents work and insure themselves against economic shocks primarily through saving. Governments tax households—at least in the formal sector—and make transfers back to them. The model is adapted, as many other macroeconomic models have been in recent months, to include disease spread and the externalities associated with each individual working and consuming and potentially infecting others as they do so.

We discipline two versions of the model. One is meant to represent the advanced economies of the world, with their relatively strong medical systems, significant abilities to tax and transfer wealth across households, small informal sectors, and older age populations. The second represents a typical developing economy, with a much younger population but a large informal sector and weak fiscal and medical capacity.

We simulate the effect of the pandemic under three main scenarios: no lockdown at all, a blanket lockdown lasting 18 weeks, and an “age-targeted” lockdown, which affects only older individuals. In all scenarios, we assume that the lockdown is enforced only in the formal sector, and that anyone can get around the lockdown by working in the informal sector, though at a productivity loss.

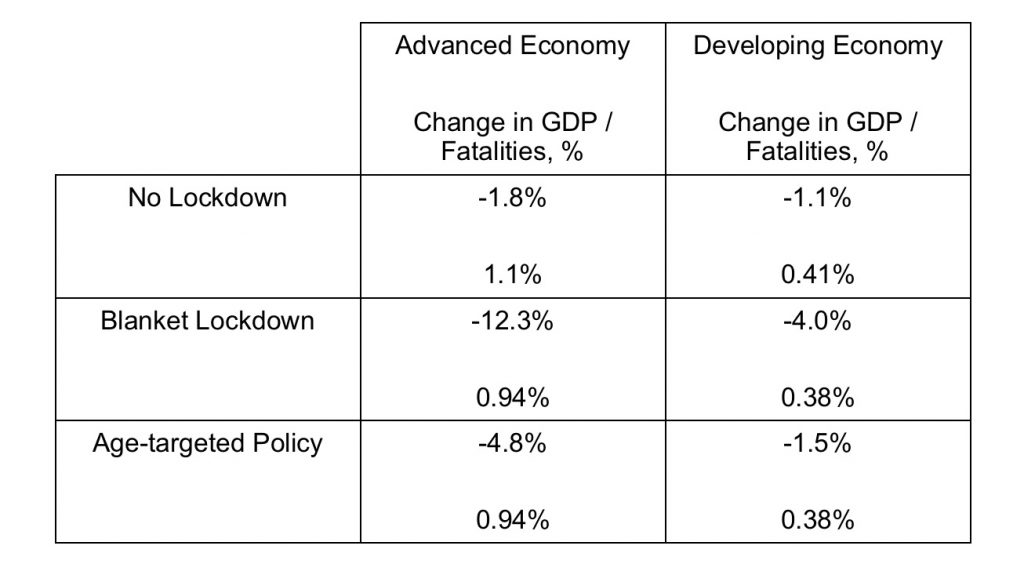

Table 1 summarizes the main predictions of the model. The first column describes what happens in the advanced economy in the model. Under no lockdown, GDP falls by 1.8 percent, and 1.1 percent of the population succumbs to the pandemic. A blanket lockdown lasting 18 weeks leads to much larger GDP losses of 12.3 percent, as households cut sharply into their work and consumption expenditures, but reduces the fatality rate to 0.94 percent of the population. Which is better is not readily apparent from these two sets of numbers, and depends on how policymakers and citizens decide to trade off lives and economic losses.

The third column reports the simulated effects of age-targeted policies targeting just older individuals (Bairoliya and İmrohoroğlu, 2020; Acemoglu et al., 2020). For expositional purposes, we choose an age-targeted lockdown lasting 28 weeks, since it leads to the same fatality rate as the blanket lockdown discussed above.

Interestingly, for this same fatality rate, age-dependent lockdowns lead to a far smaller decline in GDP per capita of 4.8 percent. The tradeoff does not depend on policymaker tastes: who wouldn’t want smaller economic losses for the same number of deaths?

The second column reports the model’s simulated effects of the pandemic in the developing economy. Absent any lockdown, GDP falls by 1.1. percent and the fatality rate is 0.41 percent, around one-third of the rate of the advanced economies. This is the younger population at work: if the disease were to naturally run its course, the deaths would be less severe in the developing world since there are so few vulnerable older individuals there. (Young people, it should be noted, are not immune to Covid-19 and could suffer long-term consequences, such as lung scarring and heart damage).

On a less positive note, blanket lockdowns in developing economies are not as effective at slowing the disease as in rich countries. A blanket lockdown lasting 12 weeks leads to a GDP loss of 4 percent but reduces fatalities by just 3 per 10,000 people.

A major factor behind this lack of success for blanket lockdowns is the informality option for workers. To begin with, around three-quarters of workers in developing economies are in the informal sector, and this sector swells in size once the lockdown is announced. As lockdowns begin to be announced, these informal workers, who continue to work outside of their homes, could continue to spread the disease, which would make flattening the curve that much harder.

On the other hand, age-dependent policies are even more effective (by some metrics) than they are in advanced economies. An age-targeted policy lasting 28 weeks in a developing economy leads to a GDP loss of just 1.5 percent and the same death rate of 0.38 percent as in the simulated blanket lockdown.

Notice that this a more attractive option, in terms of deaths and GDP losses, than any of the policies discussed for advanced economies. The reason age-dependent policies are so effective in less developed economies is that, given the limited fiscal capacity, targeting just the small number of older people actually means making transfers to them that incentivize them to remain at home and out of the workplace, rather than enter the informal sector to work. The disease spreads less quickly, particularly among older populations, which keeps fatalities down. Younger people continue to work and to earn their livelihoods, which helps slow the economic decline.

If age-dependent policies are so useful for developing economies, why haven’t more of them tried them out in practice? It turns out that many countries have in fact tried out age-dependent lockdowns, and others are beginning to follow suit. For example, Turkey imposed lockdowns targeted especially at older individuals from March through May, and Colombia has now extended its lockdowns of those aged 70 and older through the end of August 2020.

Age-dependent lockdowns in developing countries face clear implementation challenges, given that so many households in low-income countries are multigenerational. Still, when the alternative is no lockdown, as in Brazil, or strict blanket lockdowns, which put the livelihoods of so many vulnerable households at risk, lockdowns focused on shielding the elderly may represent a policy option that is better tailored to the needs of developing nations.

References

Acemoglu, D, Chernozhukov, V, Werning, I and Whinston, M.D (2020), “Optimal Targeted Lockdowns in a Multi-Group SIR Model”, NBER Working Paper No. 27102.

Alon, T.M, Kim, M, Lagakos, D and VanVuren, M (2020), “How Should Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic Differ in the Developing World?”, NBER Working Paper No. 27273.

Bairoliya, N, and İmrohoroğlu, A (2020), “Macroeconomic Consequences of Stay-At-Home Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic”, NBER Working Paper No. 27102.