A new study shows that exposure to an epidemic during one’s “impressionable years” (18-25) has a persistent negative effect on trust in political institutions and leaders, especially in democracies, suggesting a potential self-reinforcing spiral in which poor public health policy leads to deeper distrust, further undermining the effectiveness of public health policy.

It is widely argued (by Francis Fukuyama, among others) that the keys to success in dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic are “whether citizens trust their leaders, and whether those leaders preside over a competent and effective state.”

For example, Bo Rothstein ascribes the greater success that Nordic countries had at containing the coronavirus, compared to Italy, in part to greater trust in government.

Trust in government, however, is not a given. Specifically, there is a reason to ask whether Covid-19 itself will affect trust in political institutions and leaders.

New Evidence

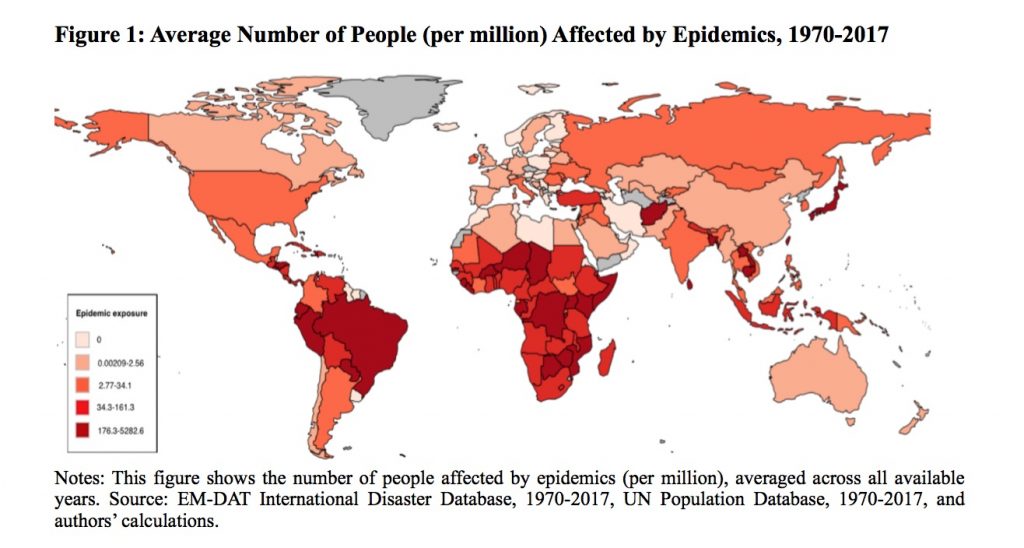

In a new paper, we provide the first evidence on the effects of epidemics on political trust. We use individual-level data on confidence in political institutions and leaders from the 2006-2018 Gallup World Polls (GWP), fielded in nearly 140 countries annually. Our data cover some 750,000 respondents from 142 countries. We analyze responses to questions about confidence in government, confidence in elections, and approval of national leaders. We link these individual responses to the incidence of epidemics since 1970 as tabulated in the EM-DAT International Disasters Database (see Figure 1).

By incorporating a wide range of fixed effects, controlling various observable characteristics as well as past exposure to other economic and political shocks, we can address potential concerns with omitted variables.

Building on previous work suggesting that attitudes and behavior are durably molded in what psychologists and sociologists refer to as the “impressionable” late-adolescent and early-adult years, we show that exposure to epidemics at this stage of life durably shapes confidence in political institutions and attitudes toward political leaders. (On the “impressionable years” hypothesis, see Dawson and Prewitt 1969 and Krosnick and Alwin 1989. For an economic application, see Guiliano and Spilimbergo 2014.)

Specifically, we find that individuals who experience epidemics in their impressionable years (specifically ages 18 to 25) display less confidence in political leaders, governments, and elections.

The effects are substantial: an individual with the highest level of exposure to an epidemic (relative to zero exposure) is 7.2 percentage points less likely to have confidence in the honesty of elections, 5.1 percentage points less likely to have confidence in their national government, and 6.2 percentage points less likely to approve the performance of the political leader. (The respective averages of these three variables in our sample are 51 percent, 50 percent, and 50 percent.)

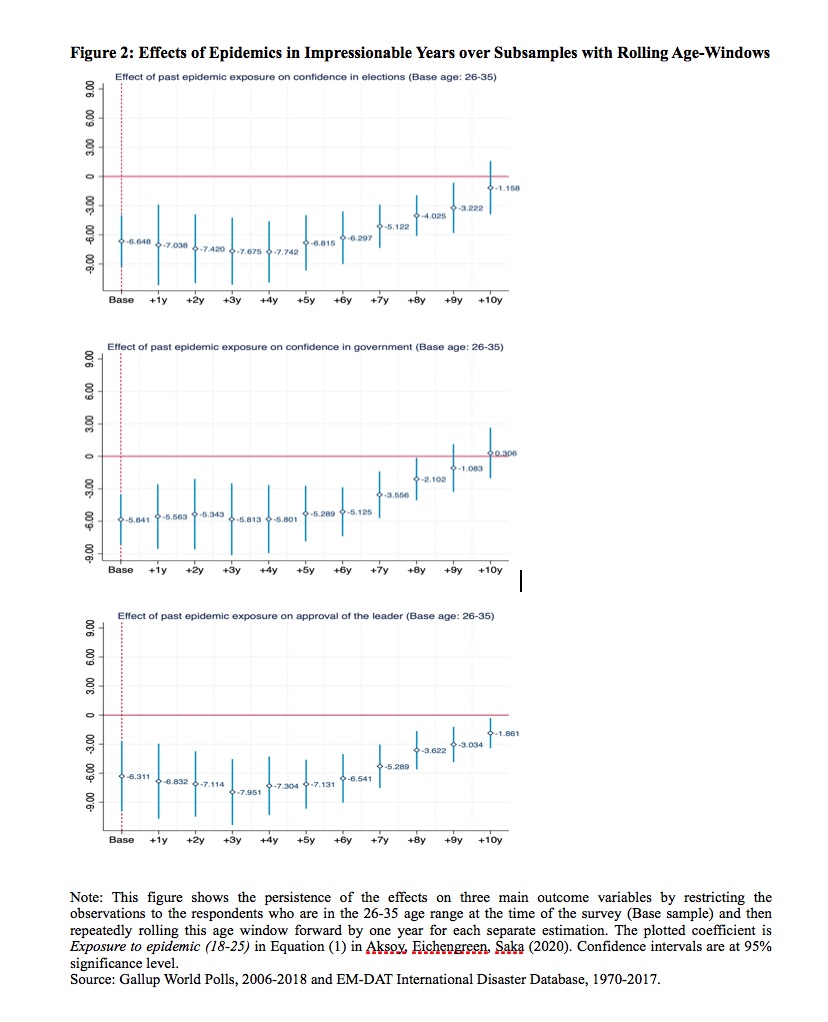

These effects represent the average treatment values for the remainder of life. They decay only gradually and persist for two decades: the difference between the median age during impressionable years (21.5) and the median age in the last subsample (40.5) corresponds to 19 years (Figure 2).

These effects are significantly heterogeneous. Less-educated individuals respond more strongly, adopting even more negative attitudes toward political institutions and leaders. Residents of urban areas respond more negatively than those residing in rural areas. Women display larger drops in confidence. The negative impact of epidemic exposure is larger in middle- and high-income countries.

Amplification and Transmission

Exploring amplification and transmission mechanisms, we show that the effects we identify are specific to communicable diseases, such as viruses, which can spread contagiously and where a timely and effective public policy response is critical for containment. For non-communicable diseases, in contrast, we do not see the same impact of past impressionable-year outbreaks on subsequent views of the trustworthiness of governments and leaders.

In addition, individuals exposed to epidemics during the impressionable period of their lives are less likely to have confidence in the public health system and the safety and efficacy of vaccines. The former is indicative of trust in the overall health policies of the government, while the latter can be taken as reflecting attitudes specifically toward pharmaceutical interventions.

These findings suggest that the perceived (in)adequacy of health-related government interventions during epidemics, both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical, are important for trust in government more generally.

Government Strength Matters

In addition, the magnitude of the effect we identify depends on the strength of the government at the time of the epidemic. When individuals experience epidemics under weak governments, the negative impact on trust is larger and more persistent. This is consistent with the idea that weak governments are less capable of effectively responding to epidemics, thus leading to a long-term fall in political trust.

We substantiate this conjecture by considering this same conditioning factor—government strength—in the context of Covid-19. We show that government strength is associated with statistically significant improvements in policy response time (the number of days between the date of first confirmed case and the date of the first non-pharmaceutical intervention). This supports the notion that government strength at the time of the epidemic is a predictor of effective policy responses and that the absence of such strength amplifies the negative revision of political trust in response to epidemics.

Finally, we show that our results are driven by the reaction to epidemic exposure in democracies. In democracies, residents sharply and persistently revise downward their political trust in the event of epidemic exposure during their impressionable years. The same is not true in autocracies.

Evidently, citizens expect democratic governments to be responsive to their health concerns, and where the public-sector response is not sufficient to curb the epidemic, they revise their views in unfavorable ways. In autocracies, in contrast, there may not exist a comparable expectation of responsiveness and hence no impact on political trust.

In addition, democratic regimes may find consistent messaging more difficult. Because such regimes are open, their openness may allow for a cacophony of conflicting official views, resulting in a larger impact on confidence and trust when things go wrong.

“Trust in political institutions and leaders among residents of democracies sharply declines following significant exposure, whereas the same is not true in autocracies.”

Conclusion

Trust and confidence in government are important for the capacity of societies to organize an effective collective response to an epidemic. Yet there is also the possibility that experiencing an epidemic can negatively affect individuals’ confidence in political institutions and trust in political leaders, with negative implications for this collective capacity.

We have shown that this negative effect is large and persistent. Its largest and most enduring impact is on the attitudes of individuals who are in their impressionable late-adolescent and early-adult years when an epidemic breaks out.

In addition, epidemic exposure during one’s impressionable years matters mainly for residents of democratic countries. Trust in political institutions and leaders among residents of democracies sharply declines following significant exposure, whereas the same is not true in autocracies.

It may be that citizens expect democratic governments to be responsive to their concerns, and therefore when government response is inadequate, they revise their attitudes unfavorably. The openness of democratic regimes may also make consistency in messaging more difficult, contributing to a cacophony of contradictory official views.

The implications are disturbing. Imagine that more trust in government is important for effective containment, but that failure of containment harms trust in government. One can envision a scenario where low levels of trust allow an epidemic to spread, and where the spread of the epidemic reduces trust in government still further, hindering the ability of the authorities to contain future epidemics and address other social problems.

As Mark Schmitt recently put it, “lack of trust in government can be a circular, self-reinforcing phenomenon: Poor performance leads to deeper distrust, in turn leaving government in the hands of those with the least respect for it.”

Editors note: An earlier version of this piece first appeared in VoxEU.org.

References

C. G. Aksoy, B. Eichengren and O. Saka (2020), “The Political Scar of Epidemics,” NBER Working Paper No. 27401.

Dawson, R. and K. Prewitt (1969), Political Socialization, Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Dustmann, Christian, Barry Eichengreen, Sebastian Otten, Andre Sapire, Guido Tabellini and Gylfi Zoega, “Populism and trust in Europe,” VoxEU (23 August).

Fukuyama, F. (2020), “The thing that determines a country’s resistance to the coronavirus,” The Atlantic (30 March).

Giuliano, P., & A. Spilimbergo, (2014). “Growing up in a recession,” Review of Economic Studies 81(2), 787-817.

Grosjean, Pauline (2019), “How WWII shaped political and social trust in the long run,” VoxEU (9 September).

Krosnick, J. and D. Alwin (1989), “Aging and susceptibility to attitude change,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 416-425.

Rothstein, B. (2020), “Trust is the key to fighting the pandemic,” Scientific American (24 March).

Schmitt, M. (2020), “In the wake of its COVID-19 failure, how do we restore trust in government?” New America Weekly (23 April).