It is often argued that the Covid-19 pandemic will reverse the ongoing trend of diminishing trust in science and scientists. A new paper finds that exposure to epidemics during individuals’ “impressionable years” (18-25) has no impact on their confidence in science, but does negatively affect their views regarding the honesty of scientists, implying that the current generation experiencing Covid-19 in their formative years may end up distrusting scientists for a long period of their lives.

Covid-19 will change everything. One effect, it has been argued, will be to reverse the secular trend of challenging the value of scientific expertise. “The coronavirus crisis has put a spotlight on the importance of science in supporting our nation’s well being.” At the same time, the pandemic has put on display certain leaders’ “longstanding practice of undermining scientific expertise for political purposes”, conceivably with negative implications for how the public views science and scientists. All of which points to the question posed by Jack Grove in the Times of Higher Education: “Will the coronavirus renew public trust in science?”

A further question is whether any change in public opinion will mainly affect views of science or individual scientists. Does any positive or negative reassessment of the importance and validity of science apply to both the undertaking and those engaged in it? Or does the public continue to have confidence in science as a potential source of a vaccine, all the while dismissing individual scientists who warn that the time needed to develop that vaccine may be lengthy?

Impressionable Years

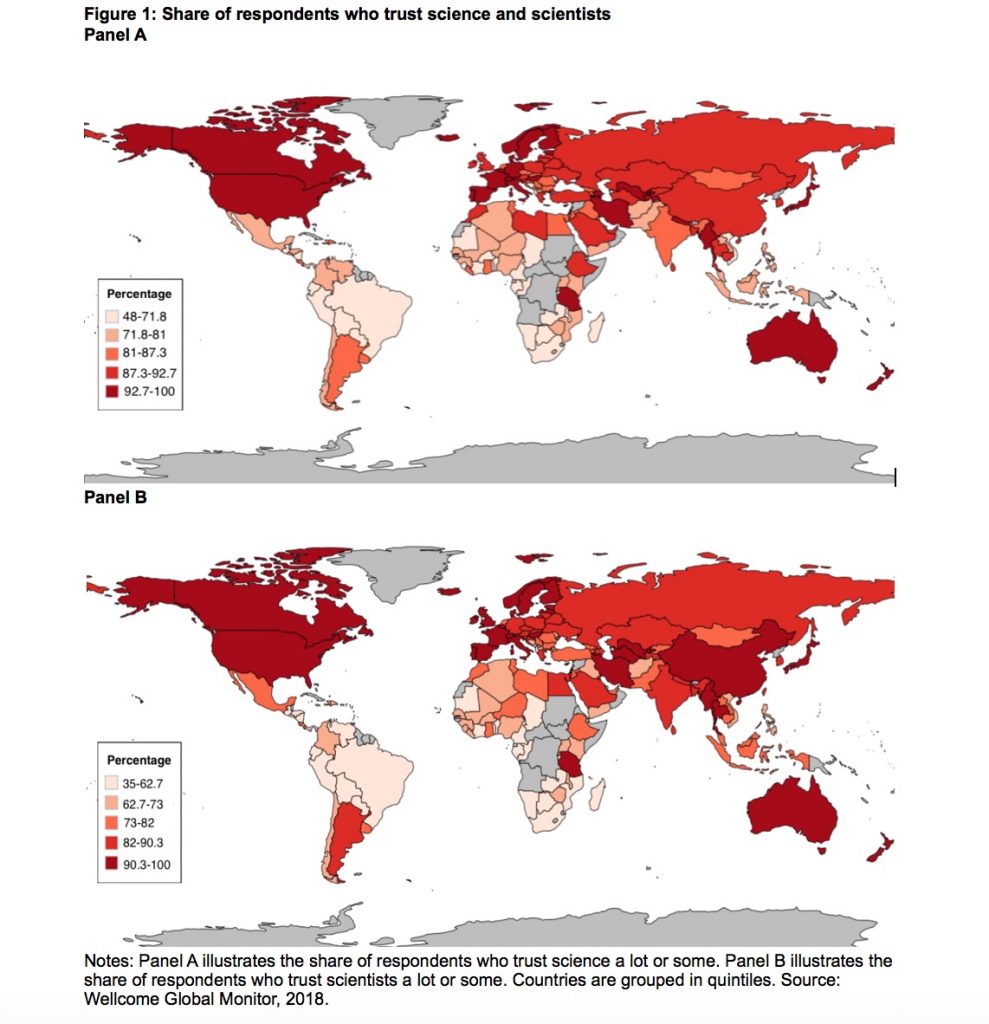

In a new paper, we analyze this issue using the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor (WGM), which includes responses to questions about confidence in science and scientists from more than 70,000 individuals in 160 countries. The responses of interest are to questions asked of all WGM respondents: “In general, would you say you trust science a lot, some, not much or not at all?” and “How much do you trust scientists” to do their work honestly, with the intention of benefiting the public? The geographical dispersion of the responses is in Figure 1.

We use data on all global epidemics since 1970 to identify respondents who experienced an epidemic outbreak in their country of residence during their formative years (18-25), the stage of the life course when value systems and opinions are durably formed.

Krosnick and Alwin (1989) formalize this as the “impressionable years hypothesis,” which states that core attitudes, beliefs, and values crystallize between the ages of 18 and 25. Spear (2000) links this to the literature in neurology describing neurochemical and anatomical differences between the adolescent and adult brain. Giuliano and Spilimbergo (2013) show, for example, that experiencing a recession between the ages of 18 and 25 has a powerful impact on political preferences and beliefs about the economy that persists over the life cycle.

Methods

To assess the effect of past exposure to an epidemic on individuals’ trust in science and scientists, we estimate models where the dependent variable is a dummy variable indicating whether or not the respondent has confidence in science or scientists.

To operationalize our treatment variable (Exposure to epidemic, 18-25) in the paper, we calculate for each individual the number of people affected by an epidemic as a share of the population, averaged over the 8 years when the individual was in his or her formative years (18-25 years old), consistent with the “impressionable years hypothesis.”

In addition, we control for observable individual characteristics (age, gender, educational attainment, marital status, religion, and urban/rural residence), labor market outcomes, and within-country income deciles), country, year, and age fixed effects, and country-specific age trends.

Scientists, Not Science

We find that exposure to the epidemic during one’s formative years has a consistently negative and significant effect for: whether the respondent has confidence in scientists; believes that scientists working for private companies benefit the public; believes that scientists working for private companies are honest; and believes that scientists working for universities are honest.

An individual with the highest exposure to epidemics (0.032, that is, the number of people affected by an epidemic as a share of the population in individual’s formative years) relative to individuals with no exposure has on average 11 percentage points (-3.454*0.032) less confidence in the honesty of scientists.

In contrast, when the dependent variable concerns science as an undertaking or endeavor (“Do you have confidence in science? Will science and technology help to improve life? Is studying diseases a part of science,” the coefficients in question are instead positive, but do not differ significantly from zero.

Evidently, individuals who experience epidemics firsthand retain confidence in the positive potential of science as an endeavor. They continue to believe in the importance of disease-related scientific research. But they are also less confident about the trustworthiness and public-spiritedness of the individuals involved in scientific endeavors.

Given that previous work points to science education as shaping views of science and scientists, we also estimate our main specification for two subsamples: respondents who learned about science at most at the primary school level, versus respondents who learned about science at least at the secondary school level.

The results suggest that our findings are driven by the sample of individuals with little or no science education. It seems that science education is at least partly able to offset the adverse impact of epidemic experience on individuals’ trust in scientists.

“Epidemic exposure between the ages of 18 and 25 continues to significantly influence public perceptions in scientists’ trustworthiness and public-spiritedness even as the respondents age over time.”

Additional Results

We examined a number of placebo tests to verify the robustness of the results. These tests address the possibility that what we are picking up is not the impact on the perceived trustworthiness and public-spiritedness of scientists engaged in health-related research specifically, but the impact on perceptions of individuals engaged in tasks related to healthcare and health outcomes more generally.

In contrast to its significant negative impact on confidence in scientists, the results of these placebo tests indicate no significant impact on confidence in doctors and nurses, in hospitals and health clinics, in NGO workers, or in traditional healers.

We also checked the persistence of this impact and confirmed that epidemic exposure between the ages of 18 and 25 continues to significantly influence public perceptions in scientists’ trustworthiness and public-spiritedness even as the respondents age over time. In other words, individuals carry the scars in their trust towards scientists for the rest of their lives.

Lastly, the effect is insignificant when individuals are exposed to epidemics in any period other than when they are between 18 and 25 years old. These results are strongly consistent with the formative-years hypothesis, implying that the current generation experiencing Covid-19 in their formative years may end up distrusting scientists for a long period of their lives.

Implications

Covid-19 promises to reshape every aspect of society, including how science is perceived. But it is not clear whether the authority of science and scientists will be enhanced or diminished, or whether such changes will affect mainly science as an endeavor or scientists as individuals.

If past epidemics are a guide, however, the virus will not have an impact on the regard in which science as an undertaking is held. But it will reduce confidence in individual scientists, worsen perceptions regarding their honesty, and weaken the belief that their activities benefit the public. The strongest impact is likely to be felt by individuals in their “impressionable years” whose beliefs are still in the process of being durably formed.

Responding to these trends will not be straightforward. At a minimum, our findings suggest that scientists working on public health matters, and others concerned with scientific communication, should think harder about how to communicate trustworthiness and honesty and, specifically, about how the generation currently in its impressionable years (“Generation Z”) perceives such attributes. In addition, our results suggest that scientific education will help.

Editors note: An earlier version of this piece first appeared at VoxEU.org.

References

C.G. Aksoy, B. Eichengren and O. Saka (2020), “Revenge of the Experts: Will COVID-19 Renew or Diminish Public Trust in Education?” LSE Systemic Risk Centre Discussion Paper No. 96.

A. Benassy-Quere and B. Weder di Mauro eds. (2020), “Europe in the Time of Covid-19,” VoxEU (22 May).

A. Benassy-Quere et al. (2020), “Repair and Reconstruct: A Recovery Initiative,” VoxEU (20 April).

L. Friedman and B. Plumer (2020), Trump’s Response to Virus Reflects a Long Disregard for Science. New York Times (28 April).

J. Grove (2020), Will the Coronavirus Crisis Renew Public Trust in Science? Times Higher Education (16 March).

P. Giuliano and A. Spilimbergo (2013). Growing Up in a Recession. Rev. of Econ. Stud. 81

J. Krosnick. and D. Alwin (1989). Aging and Susceptibility to Attitude Change, Jou. of Pers. and Soc. Psyc. 57M. Shepherd (2020), The COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic Highlights the Importance of Scientific Expertise, Forbes (14 March).

L. Spear (2000). Neurobehavioral Changes in Adolescence, Cur. Dir. in Psyc. Sci. 9.