Evidence from the United States, Japan, Korea, and Israel shows that to successfully curb the influence of large corporate entities, it is important to design and use multiple regulatory tools that can address aggregate (rather than industry-specific) economic power.

Large business entities are often perceived as important players in the economy. General Motors, Nokia, Samsung, and the tech giants of today have all contributed to innovation and growth at different time periods. Nevertheless, public sentiment may change, and some business entities can then be viewed as too large and holding excessive economic power that allows them to hamper competition and exert influence on politics and regulation.

This process may lead governments to introduce regulatory reforms, including measures aiming at breaking up, or curbing the influence of, large business entities. An early example of this process is the changing public attitude toward the railway tycoons in America during the 1880s: the negative sentiment toward them was reflected in the appearance of the term “robber barons” in the mid-1880s, and the decade ended with the introduction of antitrust legislation in 1890. A more recent example is the rise of calls for restraining the power, or even breaking up, tech giants like Amazon, Google, or Facebook.

In this short essay, we discuss government policy toward a particular type of large corporate entity—pyramidal business groups. Specifically, we study four countries that adopted measures to dismantle pyramidal business groups or limit their power.

Business groups—clusters of fully-owned (private) and partially-owned (listed, or publicly traded) firms under common control—are ubiquitous around the world and have intrigued scholars for decades.

Control-magnifying, or pyramidal, business groups—tiered structures where an apex firm controls multiple tiers of subsidiaries—let a small number of powerful individuals or families (e.g., the Lee, Tata, Wallenberg and Slim families) dominate many Asian, Continental European and Latin American economies.

These individuals or families need only have a large enough equity stake to control the apex firm; the vertical control structure of the group—the separation between control and cash flow rights—magnifies this into control over large corporate empires.

Research has explored different aspects of business groups.

Strategy scholars view the prevalence of diversified business groups in many emerging economies as a response to institutional voids—underdeveloped financial, labor or intermediate goods markets, inefficient or corrupt judicial systems, or missing innovation-supporting mechanisms that firms in business groups can bypass.

This effect is arguably important in the early stages of development, but less so in developed economies. By contrast, the downsides of business groups persist long after the economic benefits associated with them are gone: Legal and finance researchers have emphasized the resource misallocation and corporate governance problems associated with the separation of ownership and control in pyramidal group affiliates, where the controlling shareholder often has decision-making power far exceeding her equity stake, or cash flow rights.

Furthermore, excessive political power (through rent-seeking or lobbying) and monopoly power (possibly exercised through collusion, entry deterrence, predation, and more) enable “entrenchment” by groups, rendering them socially undesirable in advanced stages of economic development. The formulation of public policy vis-à-vis large business groups is, therefore, a major issue in many countries in which the social costs associated with them tend to exceed the benefits.

We focus here on four countries that, in different periods, adopted policies to dismantle business groups or contain their influence: the United States in the 1930s, Japan under the American occupation, Korea in the 1990s, and Israel in the last decade.

United States

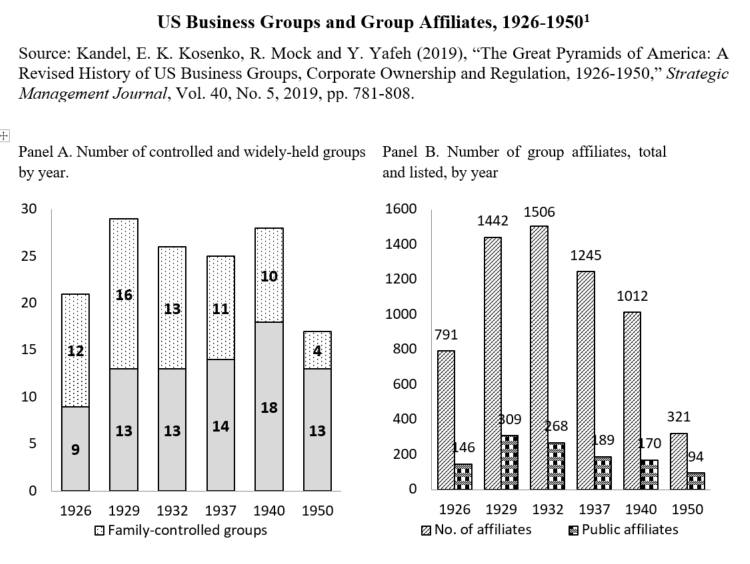

Chronologically, the first example of policy targeting business groups is the United States in the 1930s. US business groups, developed in the early decades of the twentieth century, came to own shares in multiple companies which, in turn, controlled additional tiers of subsidiaries.

Pyramidal groups with partially-owned affiliates, which wielded substantial economic and political power and controlled over half of all non-financial corporate assets in America in the early 1930s, became a major public concern and were perceived as a menace to capitalism and democracy, no less (Roosevelt, 1942).

The extreme political and economic circumstances generated by the Great Depression enabled President Roosevelt and a sequence of Democratic administrations to introduce an array of regulatory measures specifically targeting holding companies and their affiliates.

The measures included both outright restrictions on the number of levels in pyramidal groups in public utilities and on their scope of activities (designed to limit their economic power rather than to reduce minority shareholder expropriation), tax incentives to downsize groups and reduce their number of pyramidal levels (the intercorporate dividend tax), and restrictions on the scope of activities of holding companies.

The array of reforms directly targeting groups, applied consistently for more than a decade, eventually eroded US pyramids which, by and large, disappeared from the landscape of corporate America by 1950.

Japan

The second case is Japan in the late 1940s, under the US occupation. Pyramidal groups, called zaibatsu (literally, financial cliques), came to dominate the modern sectors of the Japanese economy starting in the late nineteenth century and especially in the years preceding World War II. While these groups were perceived as agents of economic development in the early stages of Japan’s industrialization, the extreme economic power of family-controlled pyramidal groups in Japan made the dissolution of zaibatsu one of the major policy objectives of SCAP (the Supreme Command of the Allied Powers in Japan).

The American occupation authorities regarded the groups not only as beneficiaries of the War but also as one of the causes of social inequality in Japan and the rise of militarism in the 1930s. In addition, the economic power of the groups was deemed detrimental to competition.

The policy measures used to dissolve Japan’s pyramidal groups were extreme: The American occupation authorities established the Holding Company Liquidation Commission (HCLC), specifically for the purpose of dismantling groups. More than one-third of all assets in the Japanese economy changed hands by decree, as the HCLC confiscated the shares held by group member firms and their controlling families. All incumbent managers were removed and prohibited from holding executive positions.

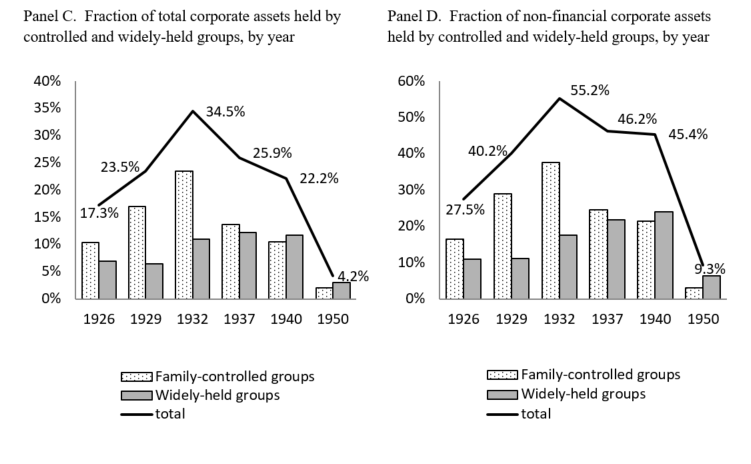

The HCLC attempted to generate a dispersed ownership structure by distributing the ex-zaibatsu shares to company employees and residents of the communities where zaibatsu-owned plants were located. The result was a phenomenal success in some important respects: holding companies, prohibited as part of the American reforms for fifty years, disappeared from the landscape of corporate ownership in Japan, as did the controlling families of the groups.

However, the dispersed ownership generated by decree through the American occupation reforms proved short-lived; cross-holdings of shares by corporations and banks generated a uniquely Japanese form of corporate ownership, sometimes referred to as the keiretsu system, a very far cry from the dispersed corporate ownership structure that the American reformers had in mind.

One possible explanation for this result is that dispersed corporate ownership cannot be imposed exogenously within a short time period and without supporting institutions. Another reason for the unexpected outcome of the zaibatsu dissolution reforms may be that the groups’ financial institutions were left virtually untouched by HCLC and could thus form the core of Japan’s postwar corporate ownership structure.

South Korea

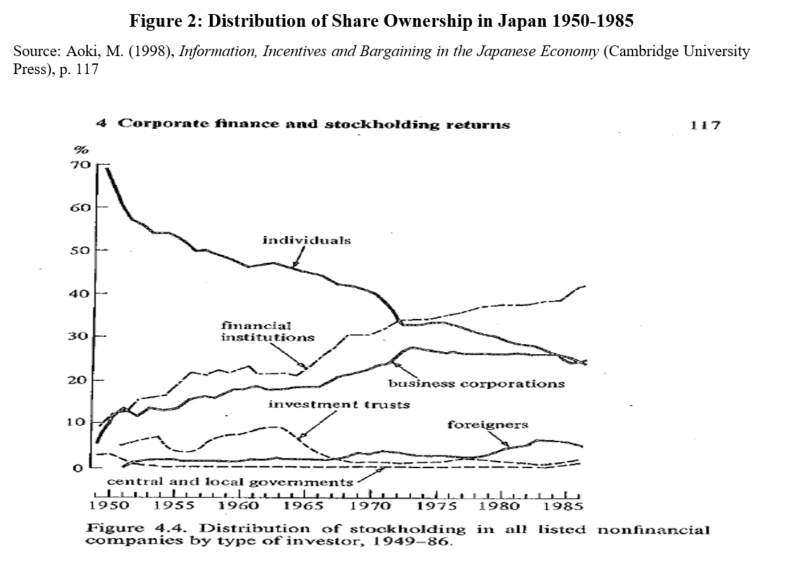

In South Korea, much like pre-war Japan, pyramidal, family-controlled business groups known as chaebol were associated with Korea’s rapid industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s, filling up institutional voids under the auspices of a developmental government. However, the groups’ rapid expansion in the 1990s, often financed by subsidized loans from government-owned financial institutions, was perceived as one of the main reasons for the economic crisis of 1997-1998, which resulted in a bailout by the IMF.

The crisis produced a (temporary) shift in South Korean politics towards a relatively “liberal” (less pro-big business) regime. Following the crisis, the perception of the large groups changed from that of paragons of South Korea’s rags to riches story to that of entities associated with “reckless behavior” and “moral hazard” (carelessness in using cheap money supplied by the government). Yet, the government did not adopt reforms to break large business groups.

The advent of the Law and Finance paradigm in the mid-1990s led to a profound change in the academic discourse on the South Korean chaebol, instilling the perception that the prevalent large wedges between control and cash-flow rights in Korean pyramids should raise serious corporate governance concerns.

Accordingly, although South Korea has experimented with various anti-big business policies at different time periods, the major policy tools used to regulate the chaebol (designed jointly with the IMF) were based on the premise that the opaque corporate governance of the groups had to be changed in order to make the chaebol less crisis-prone, more transparent and accountable to minority shareholders and to the South Korean public.

Consequently, a series of corporate governance-focused reforms were introduced in the early 2000s. At the same time, the political support for anti-big business policies was short-lived, possibly as a result of the lobbying power of the major business groups, resulting in policy changes and reversals over time.

Perhaps because of the policy focus on governance-related tools, or because of the lack of policy consistency over time, the South Korean reforms did not change the country’s corporate landscape; the largest groups, Samsung, Hyundai LG, and others, still dominate the South Korean economy. In fact, over the last two decades, the largest Korean groups have increased in size not only relative to the (now much larger) South Korean GDP but also relative to other, smaller groups.

Israel

Business groups in Israel largely emerged in the 1990s, when Israel was already a developed economy. Some groups were formed as part of an extensive privatization process in which a small number of highly-leveraged “tycoons” acquired assets previously owned by the state; other groups were formed by taking over assets previously held by families whose wealth had been eroded.

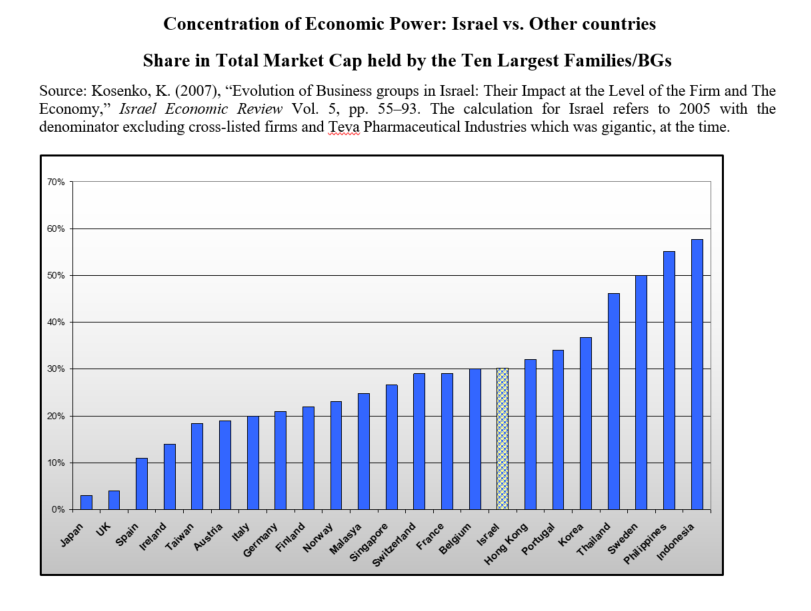

The public attitude towards these “tycoons” and the firms they controlled, which had been favorable in the early 2000s, changed around 2010-2011, against the backdrop of a high cost of living and a “social protest” condemning the monopoly power of some group affiliates (e.g., in cellular communication and retail food).

Although Israel did not experience a political or economic crisis as in the cases of the US, Japan, and South Korea, the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 precipitated the default of some group affiliates raising concerns about money invested in their securities by pension plans and other long-term savings instruments.

Against this backdrop, a government-appointed committee proposed in 2012 a set of new policies designed to limit the concentration of economic power in Israel: (i) Limiting the number of levels in pyramidal groups (reminiscent of the restrictions on public utilities in the US); (ii) Prohibiting financial and non-financial activities in the same business group, i.e., prohibiting large groups from controlling both financial institutions (banks, insurance companies, etc.) and non-financial businesses and (iii) Changing antitrust and privatization policies, so that they would no longer be based solely on industry-specific analysis, but rather take into account considerations of economy-wide concentration of economic power and control.

In addition, the Bank of Israel imposed strict restrictions on bank lending to business groups and their controlling shareholders.

The reforms in Israel, applied consistently over a period of nearly a decade, while not leading to the complete disappearance of pyramidal groups (yet?), led to a sharp decline in the number of groups in Israel today compared to 2012, before the onset of the regulatory changes. We also observe that the number of pyramidal levels and the control-cash flow wedges in surviving groups are smaller.

At the same time, some families have managed to restructure their holdings in ways that allowed them to control the same number of businesses while complying with the new anti-pyramids legislation.

The decline in group size and in the number of affiliates makes surviving groups not only smaller than groups a decade ago, but also less likely to interact with each other across multiple markets, an effect which can enhance competition.

We conclude that in order to successfully curb the influence of large corporate entities, it is important to design and use multiple regulatory tools that can address aggregate (rather than industry-specific) economic power.

Standard antitrust enforcement is unlikely to be adequate in restraining corporate entities whose activities span many industries. Standard corporate governance tools cannot be a remedy for extreme monopoly power and political clout.

We also stress the importance of the political environment in which a reform takes place, not only in having a supportive public opinion but also in the ability of policymakers to consistently apply anti-big business policies over a long time period.

Finally, the experience of Japan and Israel suggests that policies to curb the influence of business groups should probably include some form of separation of the groups’ financial institutions.