Author and former health insurance executive Wendell Potter explains to ProMarket why the employer-based health care system in the US is “collapsing” and why health insurance companies see the Covid-19 crisis as a “net saving.”

A record number of Americans—6.6 million—have filed for unemployment benefits last week, the Labor Department reported today. This brings total job losses in the US in the past two weeks to nearly 10 million, a staggering figure that highlights the severe economic impact of Covid-19.

What makes the blow even worse is the fact that millions of newly-unemployed Americans probably lost their health care insurance as well, as most US workers—nearly 150 million—receive health insurance through their employers. A similar situation happened in 2007-2009, when 9.3 million Americans lost their health insurance. The difference is that the current crisis is expected to get much worse—and, of course, that the Great Recession wasn’t accompanied by the biggest pandemic the world has seen in over a century.

To author and former-health-insurance-executive-turned-whistleblower Wendell Potter, a longtime advocate for reforming the US health care system, this unfolding crisis shows how “incredibly unreliable” the employer-based framework that has defined American health care for decades really is.

“It’s extraordinary. We’ve never seen numbers like this, and it brings into sharper focus the importance of untethering our health care from the places where we work,” he says. “Any rational person would see that it makes absolutely no sense to have your health care associated with your employment. We are always just a layoff away from being uninsured. Now we’re seeing millions of people affected in a single week, and economists are saying it’s likely to get much worse.”

What this means for the millions who have now lost their jobs and health coverage, he adds, is unclear, but not good. “For the millions of people who lost their jobs and joined the ranks of the unemployed, options are not that great. Some employers have extended benefits for a short period of time, but the Trump administration has said it’s not going to re-open the exchanges for people who become unemployed.”

Before becoming a whistleblower and one of the health insurance industry’s most vocal critics, Potter worked as vice president for corporate communications at Cigna (an experience he wrote about in his 2010 book Deadly Spin). In the past few years, he has co-authored a book on the corrupting influence of money in politics, Nation on the Take, founded the non-profit news site Tarbell, and is now the president of Medicare for All Now, a non-profit organization that advocates for universal health care.

In an interview with ProMarket this week, Potter discussed how the current structure of the US health care system is making the Covid-19 crisis much worse, elaborated on the “accelerating collapse” of the employer-based model, and explained why the health insurance industry sees the coronavirus as a potential “net saving.”

[The following interview has been edited for length and clarity]

Q: What has this crisis taught us about the US health care system, as compared to others around the world?

It’s taught us that the employer-based system through which most Americans get their health insurance is incredibly insecure. The number of people who are uninsured will take a big jump this month, and that’s solely because we rely on our employers to provide access to health care.

Another thing is that insurance companies really run our health care system. They are increasingly the gatekeepers to health care, and more and more of us are not getting the care that we need because of the practices of the health insurance industry. The way that they manage paying or avoiding paying claims is to erect barriers for people to get the care that they need. The end result is that people often postpone seeking care, and that’s especially problematic during this pandemic.

Q: Allowing millions to lose their health coverage during a global pandemic doesn’t seem like a very reliable way to run a health care system.

That’s exactly right. It is a system that has been slowly collapsing, and I think we’re going to see an acceleration of that collapse.

The only entity that is really supportive of continuing the employer-based health system is the health insurance companies, because they have made enormous profits off of the employers over many years. Employers increasingly are getting sick of being saddled with the responsibility for providing access to workers and their families.

This has been a problem for many years. During the Democratic debates earlier this year, we heard some of the candidates say that 149 million Americans have coverage through their workplace and don’t want to lose that. Of course, no one wants to lose coverage. But what they did not tell us was that 20 years ago, in 1999, about 160 million Americans were getting their coverage through their employers—now it’s down to less than 150 million. During those 20 years, as the US population increased by about 50 million, the employer-based system saw a steady decline.

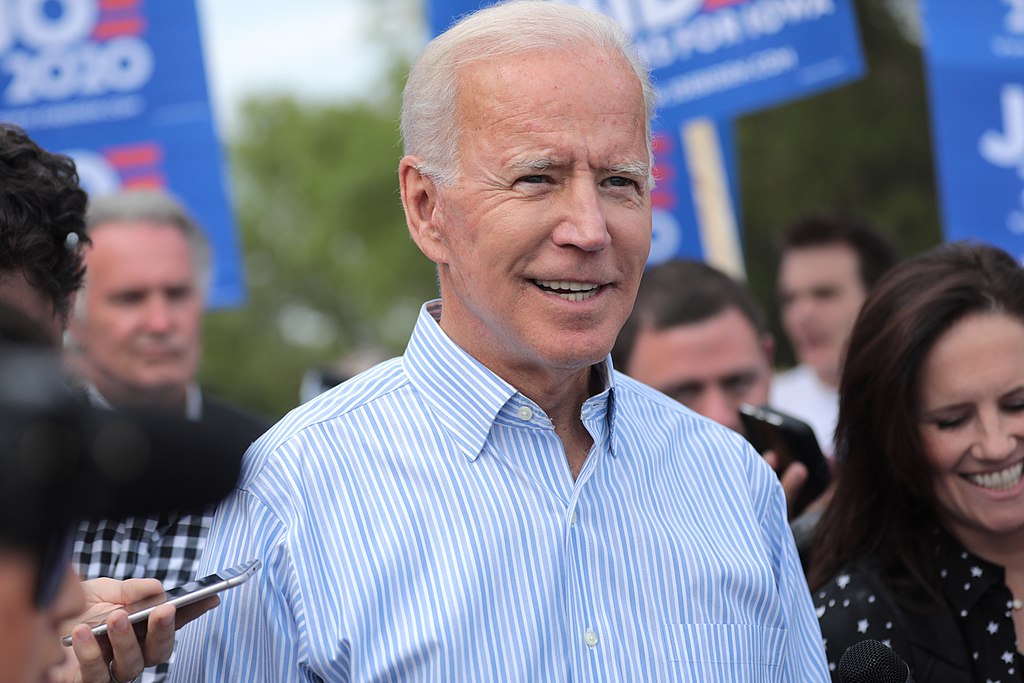

Q: Less than a month ago, after the coronavirus had already reached the US, leading Democrats like Joe Biden and (then-candidate) Pete Buttigieg were still extolling the reliability of our current employer-based system. Even now, when it’s rampaging across America, some politicians are still fiercely opposed to changing it in any meaningful way. How do you explain that?

You’re right; it was even less than a month ago that candidates on the Democratic debate stage were extolling the virtues are our employer-based system.

I think that was before there was a great public awareness of just how we are going to be affected by this pandemic, so they were able to get away with using the scare tactics that the industry has been peddling for many years and, frankly, the talking points that I used to write when I worked for Cigna.

Q: For instance?

For instance, that Americans don’t want to have a “government-run health care system.” That is a term that we used specifically. When we talk about moving to a better health care system, we’re talking about replacing our system of multiple payers with a publicly-financed health care system, not one that is run by the government, but the insurance industry has been very successful in scaring the public.

They are also able to influence candidates, including those Democrats on the debate stage, with big campaign contributions. They benefited significantly from big campaign checks and were very willing to mouth the talking points from the insurance industry to keep that money pouring into their campaigns.

Q: You used to be a health insurance executive. What was (or is) the part that this industry played in leading us to our current predicament?

There are a number of things. First, the insurance industry has no interest in making sure that everyone is covered. They don’t want to cover people who have conditions that would lead to extensive treatment, so they have ways of keeping people from getting the care that they need, or even signing up for health insurance. A lot of people in this country, even if they can technically get health insurance, just simply can’t afford it. That’s primarily why we still have 30 million people in this country who don’t have insurance, and that’s before this pandemic began.

The other thing is a big reason why I left the industry, and that’s because I was expected to be a cheerleader for high-deductible plans. We had a euphemism for these plans. We called it “consumer-driven healthcare”; the plans were called “consumer-driven health plans.”

What the insurance executives (including me) were saying back then was that the reason health care costs are going up so much is because people are using too much health care. We were able to persuade employers and individuals and policymakers that that was the real problem. In other words, the insurance industry was pointing the finger of blame at regular Americans, saying that they needed to have more “skin in the game.” They were very successful in peddling that. Regrettably, I was part of that effort to persuade employers that the way to go was to move people out of the plans that they had into these high-deductible plans.

That industry-wide strategy has been extraordinarily successful. Now, most people who have private insurance are in high-deductible plans, and most people simply don’t have the money in their checking accounts to meet their deductibles. That’s another reason why we’re especially vulnerable during this pandemic: people avoid getting the care that they need.

Q: Which leads us to an everyday reality in America that doesn’t seem to exist anywhere else in the industrialized world, which is that people have a debilitating fear of seeking medical help because they fear the cost.

It is absolutely a fear that people have, one that doesn’t exist in other developed countries. In this pandemic, I think people are going to be reluctant to get tested—even though the government is saying that the cost of testing will be covered, I’m not sure that that message has gotten to everyone.

And there is no assurance from the insurance industry that the cost of treatment will be covered adequately. Some insurance companies have said that they will waive the out-of-pocket costs for treatment, but not everyone has.

In this country, we have this constant anxiety and fear of getting sick, not just from the illness that we might get, but of having to be on the hook for a lot more money than we actually have. That’s why so many Americans turn to GoFundMe to get the care that they need, even with insurance, and why so many people wind up in bankruptcy court even with insurance.

Q: Part of that seems to be related to the incredible complexity and opaqueness of the system, no?

The system is enormously complex, far more than any other health care system. So many things that doctors and patients have to deal with are completely unknown in other parts of the world. One thing that’s common in this country is that insurance companies, even after they pay a hospital claim, have teams of people who scour those claims that have been paid looking for reasons to ask for money back—any kind of coding error, for example.

We have this enormous bureaucracy within private insurance companies that eats up the time of doctors and nurses. That’s just unknown in the rest of the world. As a consequence, doctors and nurses don’t have adequate time to treat their patients as they know they should, because they have to deal with multiple insurance companies.

Every doctor in this country has to have staff who do nothing more, day in and day out, than deal with insurance company people. It’s not just the big companies. There is a multitude of smaller companies, and each company has a multitude of healthcare plans. There’s great variation, and that requires constant telephone calls on behalf of doctors to insurance companies to make sure that they know what is covered and how much they’ll get paid when they treat a patient.

Q: So while hospitals and doctors and nurses are overwhelmed by the scale and force of this pandemic, they’re also saddled with another burden their peers in other countries don’t have: they need to make several calls to insurance companies every day on behalf of patients.

That’s exactly right. Before a doctor prescribes even a specific drug for a patient, in many cases a nurse or even a doctor has to get on a phone or check their database to find out if a particular drug is covered and to what extent.

Every insurance company has its own unique formulary. The drugs that are on there and the tiers that they are in depends on the deals that the insurance company has struck with the drug companies. Usually, the insurance company will get some discounts based on the volume of drugs that they are able to steer to the drug company. That benefits the insurance companies and the drug companies. The patients are disadvantaged, because there’s no way of really knowing until you show up at the pharmacy how much you’re going to have to pay for a medication that your doctor says you need.

| “Insurance company executives have even told financial analysts that they may have a net saving here.” |

Q: You recently said this crisis is an opportunity for health insurance companies to make record profits. This doesn’t seem to square with waiving copays on treatment and testing.

Insurance company executives have even told financial analysts that they may have a net saving here.

There are different ways that that can happen, even if they agree to cover the cost of treatment. One of the things that is happening all across the country is that hospitals are canceling a lot of procedures that had been scheduled and are not life-threatening—if someone needs a hip replacement, for example, they’re not going to get that for an indefinite period of time.

The other thing is that frankly, a lot of people are going to die, and the people who are most adversely affected are those who have co-morbidities, people who might be obese or have diabetes or lung problems or heart problems; older people, who are the costliest for insurance companies.

The number-crunchers within the insurance companies know that there’s a good chance that with all of those things factored in, they may actually emerge on the other side of this pandemic having paid out less money in claims than they otherwise would.

But even if they do have to pay more claims than that than they anticipated, they know that they can—and have already signaled that they will—increase premiums on everybody next year. In fact, the folks who run the California health care exchange, Covered California, are already saying that people in California who get their coverage from the exchange can expect to see their premium spike 40 percent. And it’s not just the Obamacare exchanges, it will also hit people who get their coverage through their employers.

The way the insurance companies have rigged our health care system, they’re probably going to emerge as financial winners from this, while the rest of us are going to be disadvantaged.

Our hospital floor is full and we need open beds for the imminent COVID surge.

But multiple patients of mine can’t leave the hospital because they’re awaiting prior auths from commercial insurers.

Insurance companies are clogging up the system in the middle of a damn pandemic.

— Augie Lindmark (@AugieLindmark) March 18, 2020

Q: You’re a longtime advocate for universal health care. In your opinion, what makes universal health care systems better equipped to handle a pandemic?

A couple of things come to mind. One, we have such a fractured system, in which there are so many payers for health care that there isn’t consistency, and people don’t know how much they’re going to have to pay out of pocket.

The other important thing is that other systems are able to devote more money to public health initiatives. We spend just about 3 percent on public health in this country—and I’ve talked to some public health experts who think that’s inflated and we spend even less than that. Other countries are better equipped because they devote more and have the ability to devote more to public health infrastructure, which enables them to prepare for and weather a pandemic like this.

Also, not only do we have a lot of for-profit insurance companies, but a lot of providers are now for-profit. A lot of physician practices are owned by private equity firms that are in it to make money. Some of them are actually owned by corporations, including insurance corporations.

So it’s all about the money in this country. It’s about making a profit, whether you’re on the insurance side or the delivery side, and that is contributing to the ever-rising costs of health care.

Americans don’t really understand it, but I think they’re coming around to understand that the free market does not work in health care like it does in other sectors of the economy. It doesn’t function at all like a free market. For one, there is no transparency of pricing. People don’t really have the choice that they’re told they have. But we’ve been told that that’s what we have and that this is what we need to preserve.

Q: Most Americans do seem to know that this is a crazy way to do health care. Polls consistently show that most Americans support some form of universal, government-funded health care system. Yet very few politicians suggest that. How do we explain this disparity between what the public wants and what politicians are willing to offer?

It’s money in politics, and I’ve written quite a bit about this as well. In fact, my last book is called Nation on the Take. When I worked for Cigna, one of the responsibilities my team had was to dole out campaign contributions through the Cigna political action committee, our PAC. And individual executives at insurance companies separately donate a lot of money to campaigns. The candidates want to keep that money flowing, and party leaders on both sides of the aisle want to keep that money flowing. Until we can really address the money in politics problem, it’s going to be more and more difficult to get us to where we need to be.

I think this pandemic is waking up members of Congress and other policymakers to realize that despite those campaign checks, despite the lobbying and talking points that people like I used to create, their constituents are suffering. I think we’re going to see more candidates supporting universal health care than we’ve seen in the past.

If possible, we need to fix not only our health care system, but our political process as well.

Q: Let’s talk about the day after Covid-19. There’s obviously going to be some push for reform, once the immediate threat is behind us. What tactics would companies use to try to stifle reform?

It shows up in different ways. One is the ongoing campaign to scare people. All the campaigns that the industry conducts are based on the principles of Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt, or FUD. They want people to fear reform. They want them to feel uncertain about it and how they’ll be affected by it and doubt those who are proposing it and whether they are really on their side.

They’re very effective. Fear works. People fear change, and the industry knows that. They know the words and phrases to use to scare people. Again, that’s what I used to do for a living.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.