In an op-ed and a white paper, Facebook’s CEO argues that “private companies should not make so many decisions alone when they touch on fundamental democratic values.” Yet he opposes any serious challenge to his company’s dominance and market power.

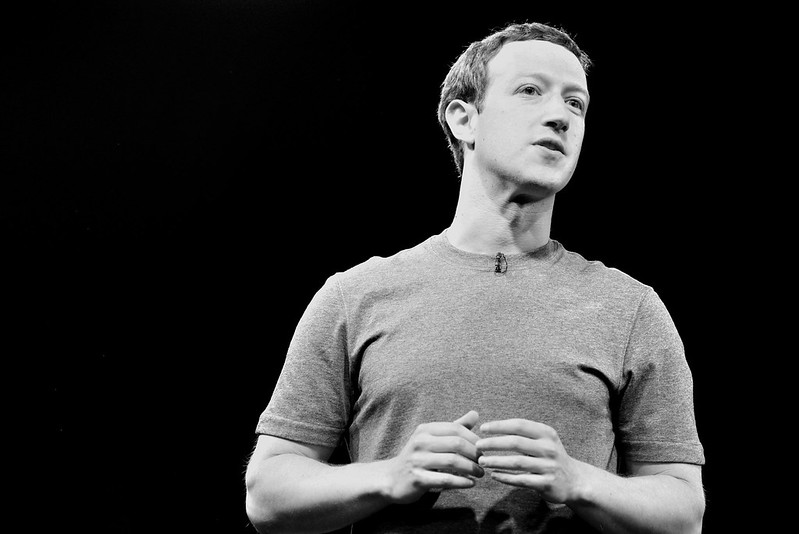

The title of Mark Zuckerberg’s op-ed in the Financial Times was catchy: “Big Tech needs more regulation.” Unfortunately, the white paper Facebook released a few hours after the op-ed’s publication makes clear what kind of regulation Zuckerberg is advocating for: a non-enforceable regulation that leaves digital platforms all the immunity and market power they currently enjoy.

What Zuckerberg and Facebook call “regulation” is actually “cooperation”: governments and international institutions should convene to question what Facebook does (and does not do) and, after extensive discussion, realize that there is no reason to put additional limits on Facebook. According to Facebook’s white paper, popular rage against digital platforms’ lack of accountability is a problem not of excessive market power but rather of asymmetric information.

People and governments do not understand how tough the life of a digital monopolist is on a daily basis.

In his Financial Times op-ed, Zuckerberg writes:

“I believe clearer rules would be better for everyone. The internet is a powerful force for social and economic empowerment. Regulation that protects people and supports innovation can ensure it stays that way.”

Facebook’s CEO argues that governments should not leave private companies the responsibility to decide on issues that are too sensitive, such as how to define and limit political advertisements during an election campaign. It’s not the first time that Zuckerberg has apparently argued for more regulation and less autonomy. He used almost the same words in a 2018 post:

“I do not believe individual companies can or should be handling so many of these issues of free expression and public safety on their own. This will require working together across industry and governments to find the right balance and solutions together.”

Since then, Facebook and Zuckerberg have always opposed any public scrutiny or limitation that could harm the company’s business model. Just two examples: Facebook has refused to pre-check contents of political ads during the 2020 presidential campaign and opposes any amendment to the notorious Section 230, the piece of legislation that makes digital platforms, unlike newspapers, not legally accountable for the content they publish.

According to US Attorney General William Barr, Section 230 has to change because the world is now very different from how it was in 1996 when Congress approved it:

“The purpose of Section 230 was to protect the “good Samaritan” interactive computer service that takes affirmative steps to police its own platform for unlawful or harmful content. Granting broad immunity to platforms that take no efforts to mitigate unlawful behavior or, worse, that purposefully blind themselves—and law enforcers—to illegal conduct occurring on, or facilitated by, the online spaces they create, is not consistent with that purpose.”

Facebook’s white paper offers a series of arguments to explain why there is no alternative to full immunity for digital platforms: “Companies are intermediaries, not speakers,” the paper argues. There is no way to impose “traditional publishing liability” because that would impact the biggest improvement that the internet has brought to public debate, which is, according to Facebook, “the ability of individuals to communicate without journalistic intervention.”

However, it is far from obvious why regulators should protect Facebook’s business model in order to preserve the quality of public debate and social relationships while, at the same time, letting newspapers die. The traditional media industry was disrupted by digital platforms’ competitive advantage when it comes to selling advertisements and publishing content with no legal limits or liabilities. Both of these advantages were the product of regulatory decisions (or rather, the lack of adequate regulation) on privacy and data. As with all regulatory decisions, these can be reversed.

The other main argument that Facebook uses in its white paper is that since digital platforms are global, regulation should be global and not country-specific. What some countries call “disinformation” or “hate speech” is simply “freedom of speech” for other countries. Some states want to regulate digital platforms to protect dissent and minorities, others to give full control to the majority. Fake information can prove more harmful than bad jokes or insults: Some countries prioritize truthful communication, others the freedom of cacophony. According to Facebook, governments should first find a common minimum standard, and only after that should they ask digital platforms to respect it:

“Any national regulatory approach to addressing harmful content should respect the global scale of the internet and the value of cross-border communications. It should aim to increase interoperability among regulators and regulations. However, governments should not impose their standards onto other countries’ citizens through the courts or any other means.”

If we take this claim literally, Congress is not supposed to regulate harmful content on Facebook unless it has first discussed a coordinated approach with the Chinese government. Any country-specific regulation would not respect “the global scale of the internet” or the global nature of Facebook’s business model, of course.

The main message of Zuckerberg and Facebook’s white paper is that the most efficient way to regulate digital platforms for governments is to define general goals and let companies decide how to pursue them. Technology evolves so quickly that politicians have no chance to regulate the details of digital operations; the internet is so global that any specific requirements or limitations would fragment interactions and communications; strict control of content would be incompatible with the very existence of digital platforms since no human or algorithm can pre-check millions of posts and videos every day.

Zuckerberg is not asking for more regulation, he is simply asking governments and citizens to accept and legitimize Facebook’s monopoly power. But as Facebook’s white paper acknowledges, “Problems arise when people do not understand the decisions that are being made or feel powerless when those decisions impact their own speech, behavior, or experience.”

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.