A new Stigler Center working paper finds that managers who resist shareholder proposals are typically acting responsibly, as opposed to acting on their own self-interest.

Conflicts and disagreements between management and shareholders are common, but the playing field is heavily tipped in favor of management due to the business judgment rule, which creates a legal presumption in favor of managers.

To gain leverage, reformers regularly seek tools that would give shareholders more influence in the hope of managing agency problems—the tendency of managers to make decisions in ways that benefit themselves rather than shareholders. The risks are especially large in many U.S. companies, where ownership is dispersed and individual shareholders have no economic incentive to organize. The movement toward deeper shareholder involvement was one of the leading reasons for the rise of activist shareholders such as Carl Icahn, Bill Ackman, Daniel Loeb, T. Boone Pickens, and Kirk Kerkorian.

A new weapon in the arsenal of shareholder activists is the shareholder proposal. In contrast to proxy fights, in which activists seek to gain control of the board, shareholder proposals allow activists to suggest specific changes in corporate policy—such as governance, compensation, or social policies—that can be approved by a vote of shareholders at large. These proposals essentially allow shareholders to cut managers entirely out of the loop. Managers often oppose shareholder proposals, arguing that the proposals benefit the special interests of the sponsors more than shareholders at large. Activists claim that managerial opposition itself is self-interested.

When managers do actively oppose shareholder proposals, are they acting in the best interest of shareholders at large or their own private interests?

That is the question investigated by John Matsusaka, Oguzhan Ozbas, and Irene Yi, all from the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business, in their new Stigler Center working paper “Why Do Managers Fight Shareholder Proposals? Evidence from SEC No-Action Letter Decisions.” After finding that the market embraces the shut-down of proposals opposed by managers, their conclusion is that managers are typically acting responsibly, as opposed to acting on their self-interest. Hence, their answer to the question posed in their paper—“To what extent do managers pursue their own interests at the expense of shareholder interests?”—is that there is actually evidence to the contrary.

Matsusaka, Ozbas, and Yi’s paper paints a picture where proposals normally come from activist shareholders, e.g. labor unions, public pension funds, and environmental groups, who may not share the interests of the shareholders at large in profit maximization. If all proposals came from shareholders at large, then managers should probably not fight them. The trickier case is whether managers should resist proposals from activists with special interest agendas. If such proposals come from activists that might be trying to capture the firm’s policies in order to pursue their private interests, their proposals should probably be resisted. If, on the other hand, their proposals are designed to discipline managers and increase value, then they should be allowed. Which of these cases prevails is the empirical question Matsusaka, Ozbas, and Yi try to answer.

Shareholders make proposals and seek to have the proposals included on the firm’s proxy statement. Management can try to omit such shareholder proposals from the proxy statement—and the law offers them a safe way of doing it: by requesting the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for a “No-Action Letter” regarding such an omission. If the SEC staff decides to grant such a letter, this means that the SEC staff will not recommend that the Commission take enforcement measures against the omission. The SEC states that its staff’s decisions are not made based on the proposals’ merit but are rather focused on making sure that “shareholders receive full and accurate information about all proposals that are, or should be, submitted to them.”

Matsusaka, Ozbas, and Yi hand-collected all 2,828 proposals for which No-Action Letters were requested from October 2007 to the end of 2016, 72 percent of which were granted and 28 percent denied. Most proposals were centered on corporate governance. The most common type of proposals seek to make it easier for smaller shareholders to call a special meeting of shareholders. The second most common proposal pushes for majority over plurality in major issues such as nominating board members, and the third most common type of proposal is to separate the roles of CEO and chairman of the board.

Matsusaka, Ozbas, and Yi measured the stock price reaction following the SEC staff’s decision whether or not to grant a letter. They reason that if the price increased following a decision to omit a proposal, the market is saying that it disliked the proposal. Conversely, if the price decreased, the market would have liked the proposal to go forward. In this way, managerial motives for fighting proposals can be inferred: if the market approves when a proposal is shut down, the managers were acting responsibly, while if the market disapproves, the managers were acting out of self interest.

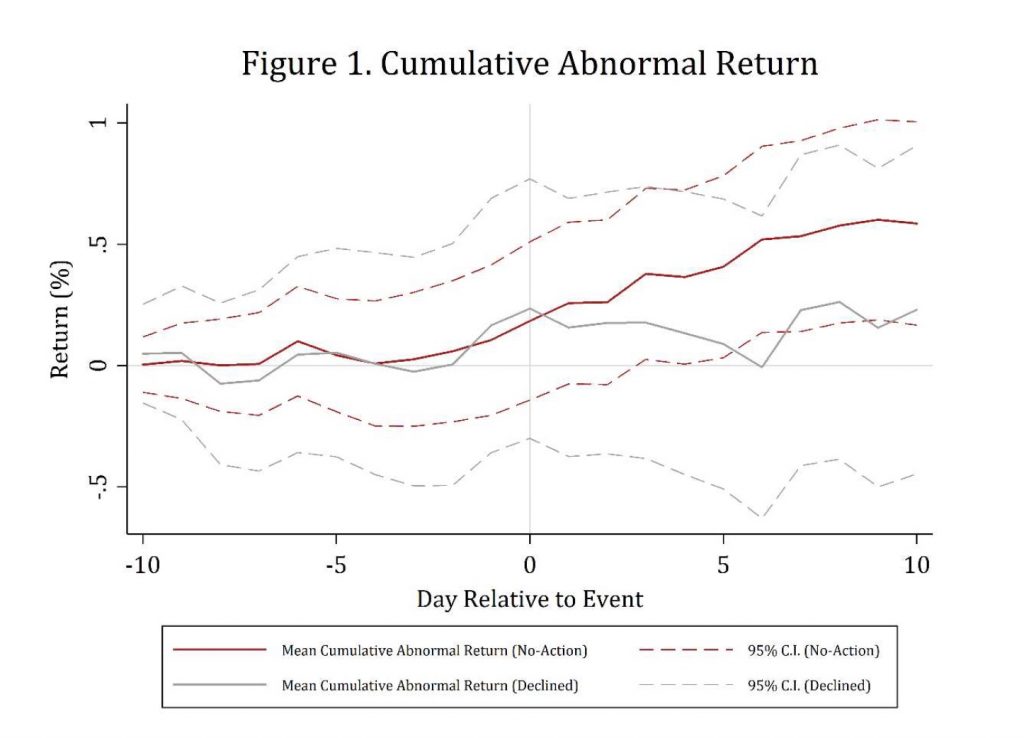

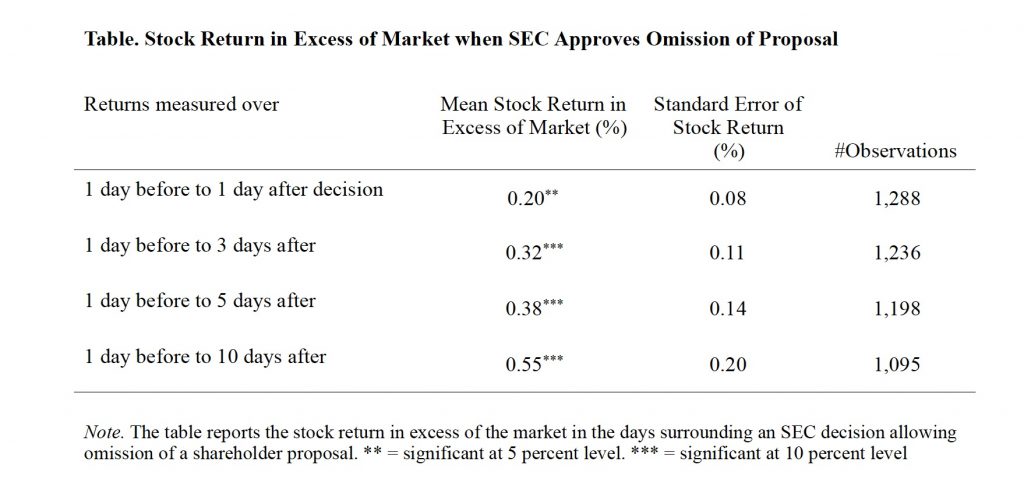

The primary novelty of the study is to examine how the market responds to omission/inclusion of a proposal, and it found that the markets responded positively to the grant of a No-Action Letter: the mean cumulative abnormal return in the days surrounding the SEC staff’s decision ranges from 0.20 percent to 0.55 percent depending on the event window; and is statistically different than zero, meaning the market approved of omitting these proposals. The authors did not find evidence that the opposite holds as well: the returns following an SEC staff’s decision not to grant a No-Action Letter are smaller, but not statistically significant.

Matsusaka, Ozbas, and Yi went deeper into the data and found that investors are specifically warier of proposals related to corporate governance, the entrenchment index (E-index), the governance index (G-Index), and proposals related to high profit firms. The finding on high versus low profit firms implies that the market dislikes governance proposals at high profit firms, plausibly because they don’t want to try and fix something that is working. On the other hand, the market does seem to like governance proposals at low profit firms. Matsusaka, Ozbas, and Yi found no evidence that the post-announcement decision was related to proposals that were put forward by certain types of investors, e.g. pension funds or labor unions. This may suggest that singling out proposals based on the identity of their sponsors does not yield additional information.

The findings may be tempting enough to conclude that shareholder proposals are damaging and that maybe the trend of increasing shareholder influence has poor empirical backing. But Matsusaka, Ozbas, and Yi caution against this conclusion: “This,” they write, “does not imply that the process itself lacks value, only that some uses of it are harmful. A more holistic analysis would be necessary to draw conclusions about the overall value of the process, but our analysis suggests that the idea of a positive net value cannot be taken for granted; it requires evidence of concrete benefits that would offset the costs we find.” In fact, they say, their study might mean that competitive pressures may be more effective than is commonly believed in offsetting managerial agency risks.

The study can speak to capture by special interests. One way to interpret the findings is that special interest activist shareholders—labor unions, public pension funds, and environmental, social, and governance groups—are trying to influence corporations to change their policies in ways that align with special interest goals but would harm shareholders at large. The shareholder proposal process might have value in allowing shareholders to control managers, but at the same time it might have a cost in allowing special interest shareholders to partially capture the company’s policies.

In a conversation with John Matsusaka we asked: Isn’t the leap from abnormal returns to concluding that managers act responsibly too big? Isn’t it especially true, considering that Matsusaka and his co-authors examine only a few days’ returns?

Matsusaka explains: “Our study relies on a research method with a very long pedigree called ‘event studies.’ The method relies on an implication of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, that all public information about a security is incorporated into its price. A great deal of research shows that new information is incorporated rapidly, typically in less than a day.

“Our paper studies the market reaction to an SEC announcement either allowing or omitting a proposal; the price reaction on the day of the announcement (we actually examine more than one day just in case information takes a bit longer to reach the market) indicates the market’s assessment of how the news affects the discounted present value of the firm. Put more simply, the market reaction tells us how investors think a proposal will affect firm value.

“So our finding that firm value goes up when the SEC shuts down a proposal indicates that investors believed the proposal would have reduced firm value (if it had not been shut down). In this sense, we can conclude that the managers were acting responsibly: they were trying to shut down proposals that investors believed would have harmed shareholders. If we had found a negative market reaction, it would have meant that investors are disappointed by the omission, that is, they expected the proposal to increase value, and thus managers were not acting in shareholder interests.

“I think it is important to note that we focus on average returns. Our finding that investors like it when proposals are shut down, on average, does not mean they like every proposal to be shut down. Indeed, there are some proposals for which the market reaction is negative when they are shut down, indicating that investors would have preferred for those proposals to go forward. So we are not arguing that managers always act responsibly, only that they seem to be acting responsibly for most shareholder proposals that they resist.”

Finally, we asked Matsusaka why the SEC provides No-Action Letters. Matsusaka said: “This is a good question without an obvious answer. The SEC provides no-action letters for other securities-related actions as well. The idea is to provide a service for companies that want to be in compliance with the law but are not sure if their proposed action would be in compliance or not. Roughly speaking, the company is saying: ‘We want to do X. Can you tell us if this seems inconsistent with existing law?’ So the SEC, in some sense, is providing free but non-binding legal advice. Companies can choose to ignore the SEC’s no-action letter advice and proceed anyway, presumably intending to defend their action in court if the SEC brings an enforcement action.”