In new research, Yusheng Feng, Haishi Li, Siwei Wang, and Min Zhu show that higher industrial subsidies raise the likelihood and severity of foreign antidumping and countervailing duties. These retaliatory duties wipe out roughly a quarter of the revenue growth the subsidies would otherwise create for firms. Failing to address the potential consequences of subsidies may lead governments to overstate the net benefits of industrial policy and fuel deeper trade frictions.

Governments use subsidies to speed up growth in priority sectors. By reducing investment risk and boosting expected returns, they encourage firms to enter markets, scale up their operations, and gain experience and know-how. In China, sustained subsidies for renewable-energy manufacturers lowered production costs and supported capacity expansion, helping the country achieve global leadership in both manufacturing and installation.

However, in new research we examine how subsidies can backfire by leading to retaliatory duties that end up countering many of the intended benefits of subsidies. Over the past two decades, World Trade Organization (WTO) members have targeted China with antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) investigations and measures. The main drivers are the scale and speed of China’s export growth, recurrent overcapacity in sectors such as steel, solar, and chemicals, and extensive state support for its companies that trading partners view as unlawful and injurious. Influential cases include the European Union’s 2024 CVDs on Chinese electric vehicles and the United States’ 2012 AD/CVDs on Chinese solar cells/modules, which further extended to modules Chinese firms assembled in Southeast Asia after 2023.

Although China’s subsidies have allowed its firm to gain international market share, we find that AD/CVD duties targeting Chinese government-subsidized firms claw back 22% of the subsidies’ positive effect on firm revenue growth. The unrealized expected gains of subsidies may be a reason for the Chinese government to rethink the utility of its industrial policies.

Subsidies lead to greater foreign anti-dumping and countervailing duties

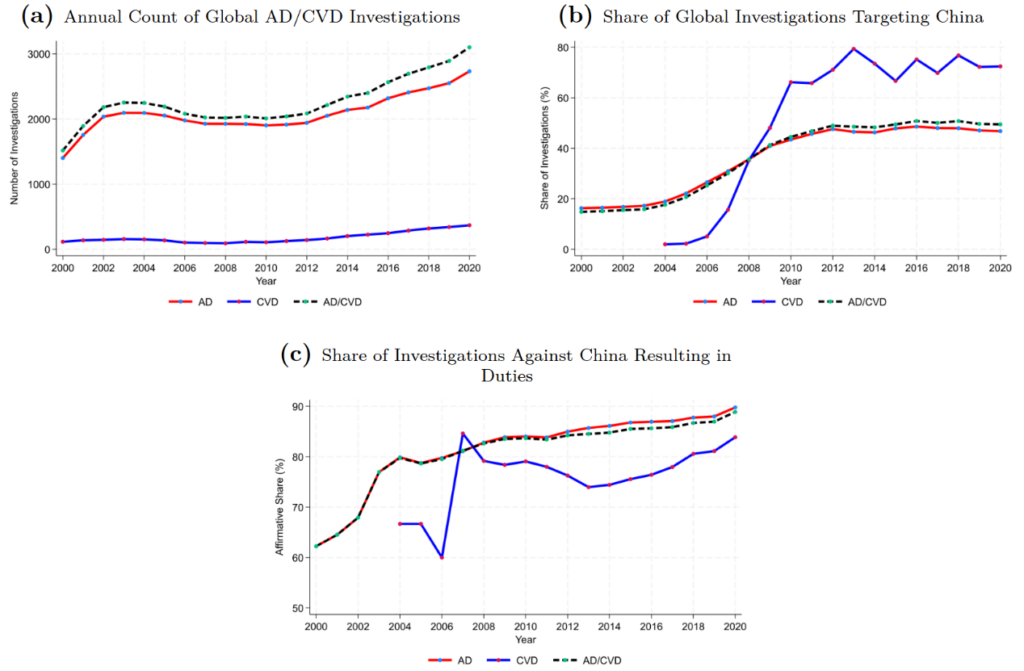

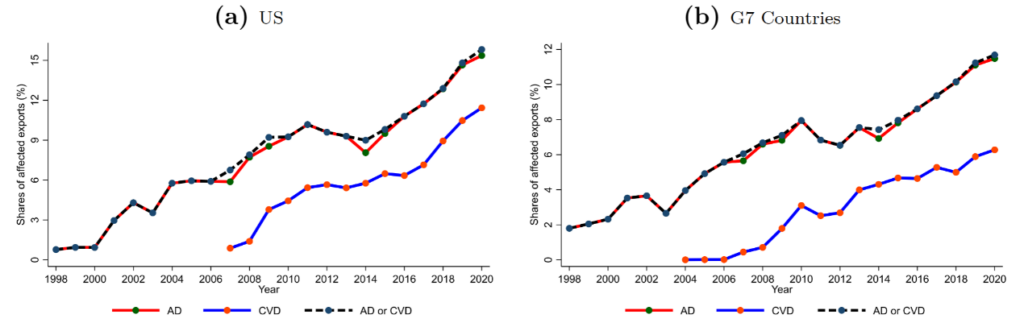

Globally, AD/CVD cases against China account for roughly one-third of all cases. Both the frequency of investigations and the share of investigations resulting in duties against Chinese goods have increased significantly since 2000. By 2020, around 15% of Chinese exports to the U.S. and 12% of those to G7 countries (United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Germany, and Italy) were subject to AD/CVD duties, with the affected share increasing over time from around 0-2% in 2000 (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 1: Trends in Global AD/CVD Investigations and China’s Exposure

Figure 2. Shares of Chinese Exports to the US and G7 Countries Facing AD/CVD Duties

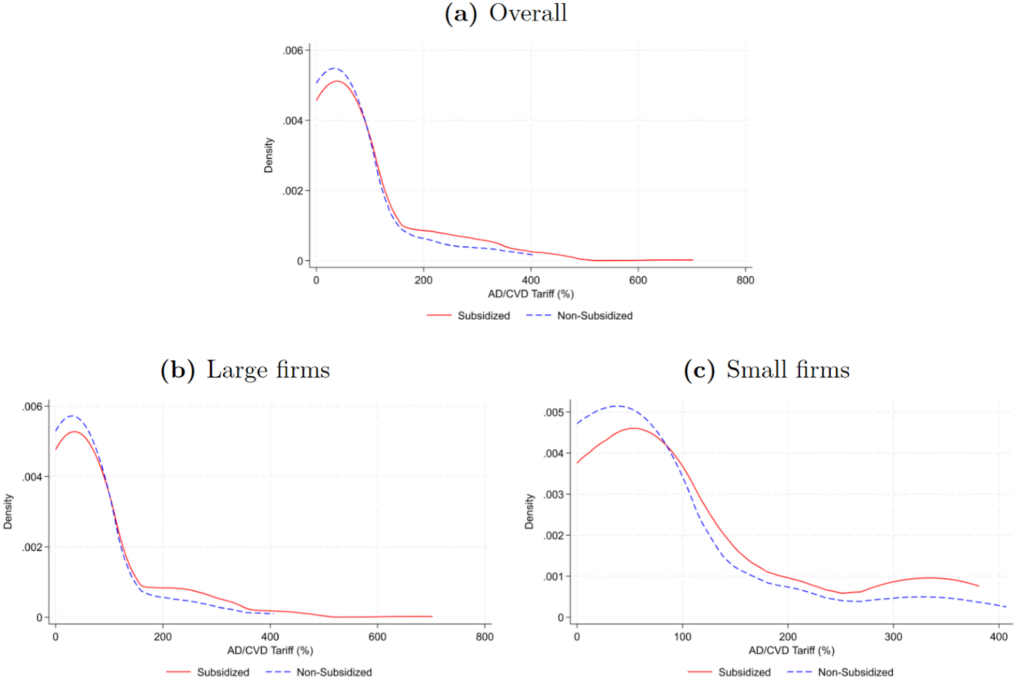

Moreover, subsidized firms are disproportionately affected. Under WTO rules, authorities may impose CVD when a specific subsidy injures a domestic industry and impose AD when imports are priced below “normal value” and cause injury. Figure 3 shows that the distribution of duties for subsidized Chinese exporters is significantly higher compared to non-subsidized Chinese exporters. This is true for both large and small firms.

Figure 3: AD/CVD Duty Distribution for Subsidized and Non-subsidized Chinese Exporters

Within each AD/CVD investigation, some exporters can qualify for their own (firm-specific) duty rate, while others default to the product-wide rate. Generally, product-wide rates are much higher than those for specific firms. The average product-level duty is 145% of the product price while the average firm-specific duty is 81%. Using data on Chinese industrial firms and retaliatory duties cases against China, we find that higher industrial subsidies consistently lead to more punitive outcomes. Specifically, at the product level, goods exported by heavily subsidized firms are more likely to receive affirmative AD/CVD rulings, which lead to duties. Among those affirmative cases, higher industrial subsidies lead to higher duty rates.

At the firm level, firms receiving larger subsidies are less likely to be granted a favorable, firm-specific duty rate. Instead, they are more likely to pay the higher product-wide duty rates. Among those that do receive firm-specific treatment, higher subsidies are still associated with higher assigned duty rates.

The hidden costs for subsidized firms

Subsidies increase the chance of higher duties. We find that a one percentage point increase in a firm’s subsidy rate (defined as total subsidy revenue received from the government as a percentage of the firm’s total output) raises its expected duty rate by 0.16 percentage points. Despite what appears to be a moderate average effect, the highly skewed distribution of subsidy rates means the most heavily subsidized firms face very high duties. A firm increasing its subsidy rate from the 5th percentile (0%) to the 99th percentile (115%) could see a duty rate that increases by nearly 18 percentage points.

Moreover, among firms levied duties, those receiving larger subsidies are less likely to be granted the lower firm-specific rates. When they are, they tend to face higher firm-specific duties than less-subsidized firms, as their subsidy information undergoes closer scrutiny during the investigation. Quantitatively, a one-percentage-point increase in the subsidy rate reduces the likelihood of obtaining a firm-specific rate by 0.7 percentage points and raises the assigned firm-specific AD/CVD duty by about two percentage points. Given that the average product-level duty is 145% while the average firm-specific duty is 81%, this translates into an overwhelming 47 percentage point increase in the expected duty faced by firms potentially eligible for firm-specific treatment.

The intended benefits of industrial subsidies on firm revenue growth, employment, and productivity are partly offset by increased foreign trade protection. We compare five-year revenue growth across firms with different subsidy levels, both with and without accounting for AD/CVD tariffs. When duties are omitted, a one-percentage-point increase in the subsidy rate raises firm revenue by 1.2%. When duties are accounted for, the same subsidy yields only a 0.9% gain. This 0.3-percentage-point gap indicates that retaliation offsets roughly one-quarter of the subsidy’s growth effect. Similar attenuation appears in firm-level employment and productivity growth.

Conclusion

Existing research has documented the widespread use of industrial policies in countries such as China, the U.S., and the EU. The same research has also documented how this industrial policy produces cross-border spillover effects that intensify competition and harm firms and workers abroad across trading partners. We provide first evidence on how domestic subsidies trigger foreign AD/CVD duties. Our findings reveal a hidden cost of industrial policy: under WTO rules, subsidies lead to AD/CVD duties that offset about a quarter of the subsidies’ positive effect on firm revenue growth.

This mechanism is especially relevant for policymakers worldwide given the widespread use of industrial policy, the growing reliance on AD/CVD for trade protection, and the parallel escalation of trade wars that bypass the WTO framework. Overlooking the risk of foreign trade protection makes subsidies appear more beneficial than they really are, directs public funds toward sectors likely to face retaliation, and ultimately reduces revenues, profits, and efficiency—undermining the very growth those subsidies intended to promote. Policymakers aiming to promote exports should consider how subsidy design shapes trade response, targeting sectors that impose less foreign harm (such as advanced technology or domestic consumption), or relying on alternative, non-subsidy tools (such as structural reforms), that are less likely to trigger foreign trade retaliation.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.