In new research, Riley Acton, Emily Cook, and Paola Ugalde find that college campuses in the United States have become increasingly polarized over the last few decades, and both liberals and conservatives are willing to pay much more to attend colleges with likeminded peers.

Political polarization has become a defining feature of American society. Political views shape where people live and work, whom they befriend, and even whom they date. Our research shows that these patterns extend to one of the most consequential decisions young adults make: where to attend college.

Drawing on four decades of data on college first-year students in the United States and a new survey-based experiment, we document two key patterns. First, colleges have become increasingly polarized. Though colleges in general have become more liberal since the early 1980s, the gap between the most liberal and most conservative institutions in terms of the political composition of their student bodies has widened dramatically. Second, our experimental evidence suggests that students exhibit a preference for politically aligned environments when making their college choices. Both liberals and conservatives are willing to pay thousands of dollars more to avoid campuses with a large share of students of the opposing viewpoint. These patterns matter both for higher education and society at large. They risk reducing students’ exposure to diverse viewpoints and exacerbating the political divides that concern many Americans today.

Four decades of change in student political views

We begin our analysis by examining responses to the Freshman Survey, administered by UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute (HERI). Since the 1960s, more than 15 million incoming first-year college students have completed this survey, reporting valuable information on their backgrounds, expectations for college, and, importantly for our analysis, their political leanings.

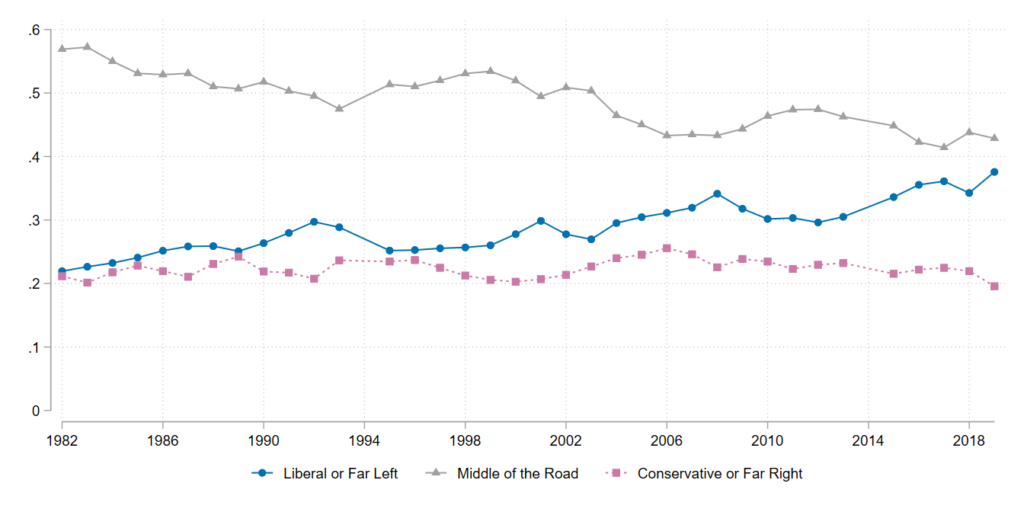

Figure 1 plots the political identification of college freshmen from 1982 to 2019. The figure shows that in the early 1980s, the proportion of students identifying as liberal and conservative coincided at roughly 21–22 percent each, with a majority of students identifying as “middle of the road.” Since then, however, the liberal share has risen steadily, reaching nearly 38 percent in 2019, while the conservative share has remained stable at around 20 percent. The growth in students identifying as liberal has, therefore, come primarily from a decline in the moderate share.

Figure 1. Trends in Students’ Political Views, 1982–2019

A Widening Distribution Across Institutions

The overall shift towards liberal identification reflects national trends but masks important differences across types of colleges. Liberal identification has grown the most at selective research universities, liberal arts colleges, and historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). In contrast, non-Catholic religious institutions have become more conservative.

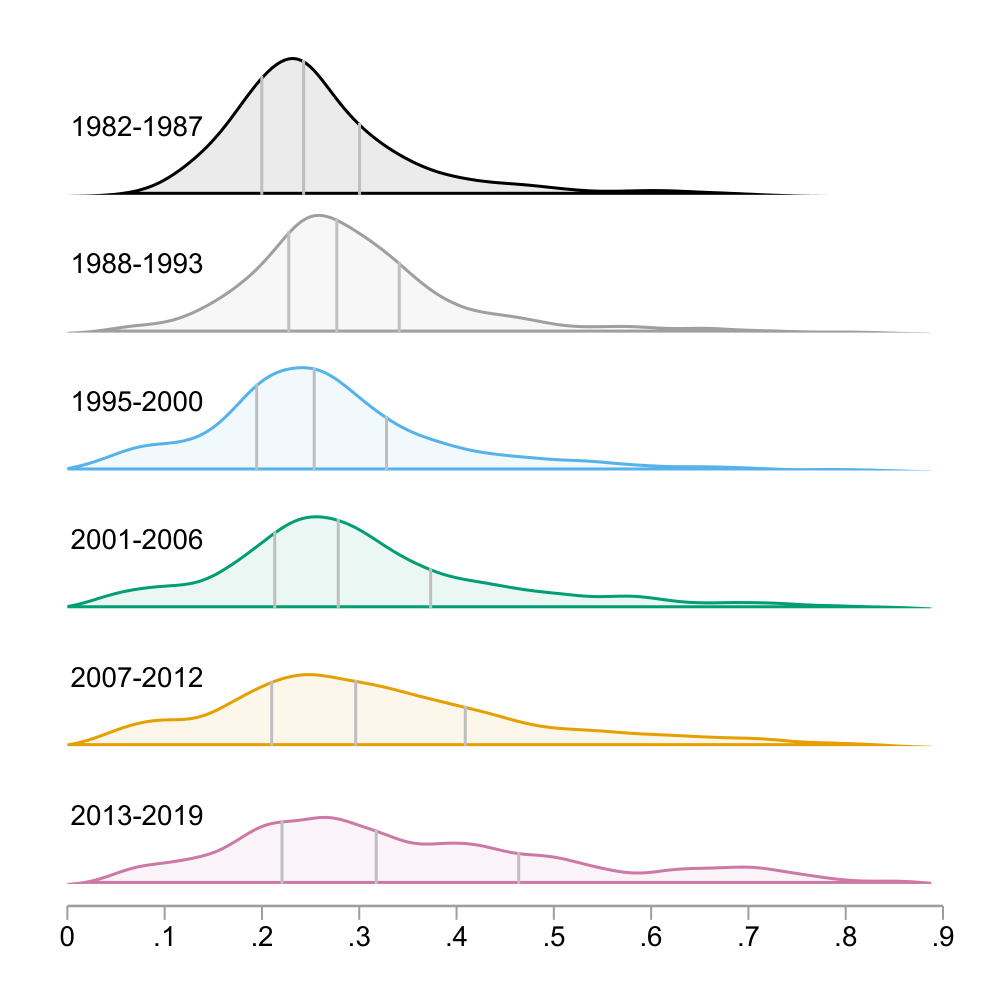

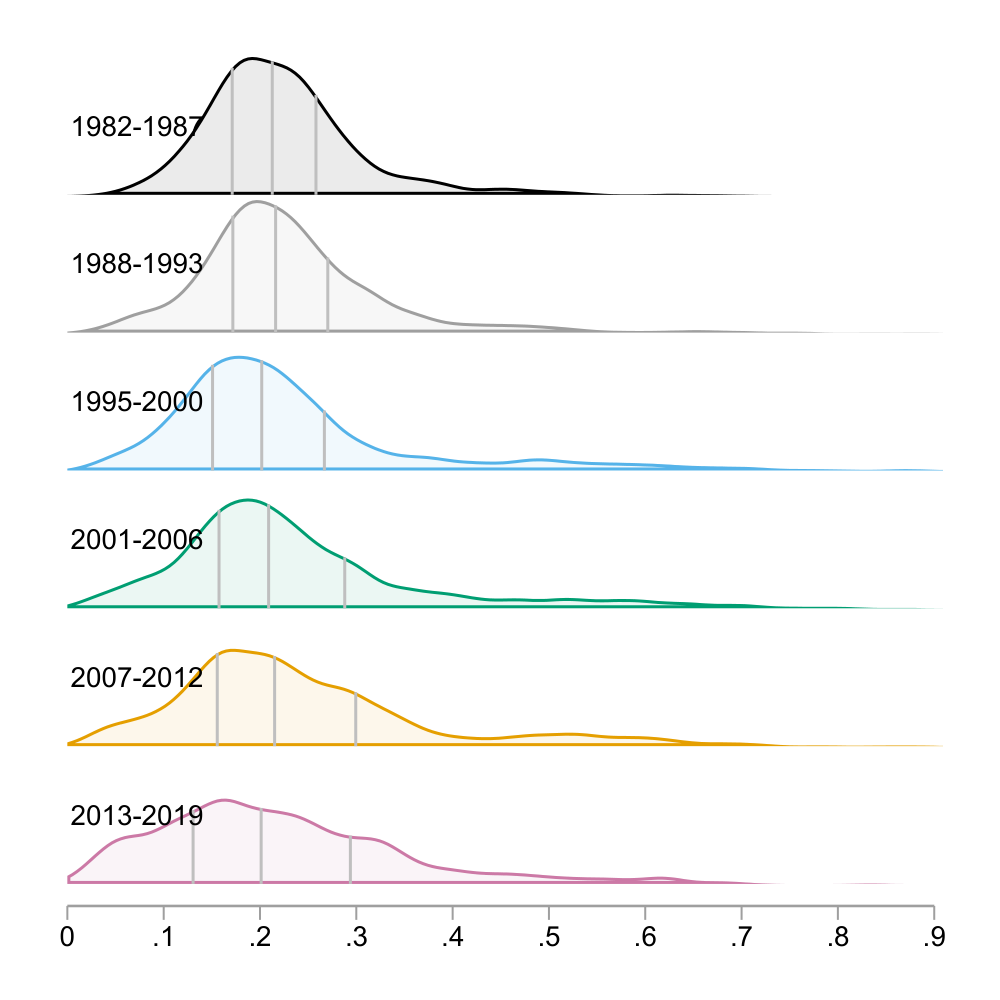

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the share of liberal students across colleges in six time periods between 1982 and 2019, with vertical lines indicating the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles. In the early 1980s, most campuses clustered around 20–30 percent liberal students; the interquartile range (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles) was just 10 percentage points, meaning half of college campuses fit this description. By 2013–2019, the distribution had both shifted and stretched: the median share identifying as liberal rose, and the interquartile range expanded to 24 points. In other words, while the typical campus became somewhat more liberal, the upper tail—those with already very high concentrations of liberal students — became much more liberal. Figure 3 presents a similar pattern for conservative identification. The distribution widened from an interquartile range of 8.7 percentage points in the 1980s to 16.3 points by the 2010s, indicating that some campuses became substantially more conservative even as the national average held steady.

Taken together, these figures provide evidence of increased polarization across colleges: institutions with liberal-leaning student bodies in the 1980s became more liberal, while those with conservative-leaning student bodies became more conservative. In a series of regression analyses, we further show that this divergence is not well explained by changes in any observable factors of students, such as race, religion, academic preparation, or geographic background. Even after accounting for these characteristics, the ideological distance between colleges continues to widen.

Figure 2. Distribution of Liberal Students Across Colleges, 1982–2019

Figure 3. Distribution of Conservative Students Across Colleges, 1982–2019

Do students care about politics when choosing colleges?

One possible explanation for why college campuses are politically polarized is that political preferences directly influence students’ college choices, inducing like-minded students to attend college together. To investigate this question directly, we designed a survey-based choice experiment with over 1,000 undergraduates. We presented participants with pairs of hypothetical colleges that varied across standard attributes — such as cost, distance, selectivity, and size — as well as political attributes. Specifically, we provided them with the partisan composition of the student body and the voting record of the state in the 2024 presidential election. Students then reported the probability they would choose to attend each college. We use the responses to these questions to estimate students’ preferences for different college attributes.

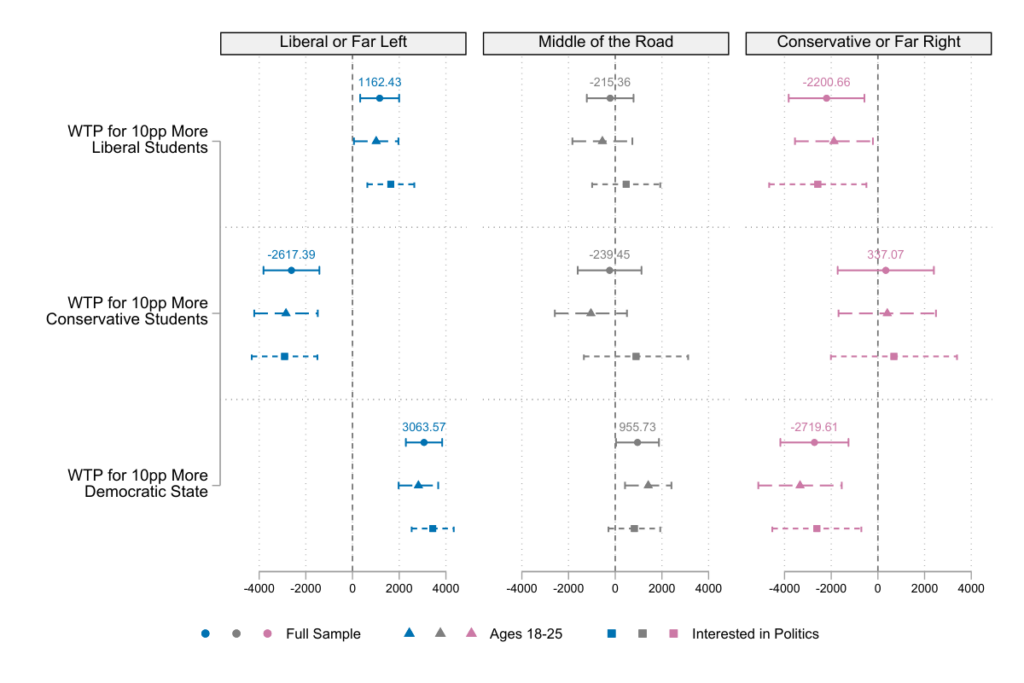

In Figure 4, we present willingness-to-pay estimates that reflect the value students place on political attributes. The results reveal an asymmetric pattern. Both liberals and conservatives care about avoiding peers with opposing views. Liberals are willing to pay roughly $2,600 more per year to attend a college with a 10-percentage-point lower share of conservative students, while conservatives are willing to pay about $2,200 more to attend a college with 10 percentage points fewer liberal students. By contrast, students place far less value on the share of like-minded peers: the average liberal is willing to pay about $1,200 more for an additional 10 percentage points of liberal students, and conservatives exhibit no statistically significant willingness to pay for more conservative peers (vs. moderate ones). We believe this asymmetry is reflective of a broader phenomenon in political behavior known as affective polarization, where Americans increasingly express more negative attitudes towards opposing political parties and, in our setting, wish to avoid them.

Figure 4. Willingness to Pay for Politically Aligned Campuses

Broader implications

The consequences of political sorting in higher education may be far-reaching. The decline of political diversity within campuses means fewer opportunities for students to encounter and engage with opposing viewpoints. Therefore, if students self-select into politically homogeneous institutions, they forgo the type of exposure to diverse viewpoints that prior research has shown can foster tolerance and reduce animosity.

Because political identity in the U.S. increasingly correlates with geography and socioeconomic status, political sorting also amplifies existing macroscopic inequalities. We document that elite universities — pipelines to high-paying jobs and positions of influence — are increasingly liberal, while conservative students are overrepresented at less selective or regionally oriented colleges. This imbalance risks entrenching disparities in access to the social and economic benefits of selective higher education.

Finally, colleges shape future leaders in government, business, and civil society. If those leaders are educated in ideologically uniform environments, they may be less equipped to understand or engage constructively with opposing views, fueling further partisan division at the highest levels. Some universities and states have recently begun experimenting with programs to foster “viewpoint diversity” or to broaden recruitment and admissions strategies to reach students from a wider range of political backgrounds. Such efforts will face an uphill battle if students themselves prefer to avoid ideological diversity. Alternative approaches that counteract this tendency will likely be necessary to achieve college leaders and policymakers’ goals to encourage viewpoint diversity and reduce polarization.

Authors’ Disclosure: This research was supported by the Miami University Ryan Center for Economic Opportunity and the LSU Provost’s Fund for Innovation in Research. The research reported in the article was made possible (in part) by a grant from the Spencer Foundation (#202600020). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Spencer Foundation. You can read ProMarket’s disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket‘s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket‘s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.