In new research, Priyaranjan Jha, Jyotsana Kala, David Neumark, and Antonio Rodriguez-Lopez find that studies arguing higher minimum wages have no employment effect—or even a positive effect—in many labor markets fail to account for how much less minimum wages matter in larger, higher-wage cities.

Two staples are enshrined in economics textbooks and taught to generations of students. First, labor markets are competitive, and thus wages are at their market-clearing point, where the supply of labor is in equilibrium with labor demand. As a consequence—and the second staple—a higher minimum wage will reduce the number of jobs businesses are willing to offer low-wage workers, since higher wages raise costs for businesses and prices for consumers, thus reducing overall employment for affected workers.

The vast majority of studies on the effects of minimum wages support this conclusion. But a small number, including the famous New Jersey-Pennsylvania fast-food study, claim that higher minimum wages increase low-wage employment or, more commonly, do not affect employment at all. Proponents of higher minimum wages have latched onto these latter studies, as well as recent evidence suggesting some labor markets are less competitive, to argue for jettisoning the competitive model of the labor market, and in particular its prediction that a higher minimum wage reduces employment. Our new research suggests these proponents are mistaken: what looks like evidence of monopsony or labor market power softening job losses is largely explained by the fact that in larger cities wages of low-wage workers are already well above the minimum wage and minimum wages simply do not bite as much.

Theory and evidence on the minimum wage and employment

The prevailing theory explaining findings of no effects or even positive effects of minimum wages on jobs is that low-skill labor markets are actually not competitive. Since George Stigler published his famous paper discussing minimum wage legislation, economists have agreed that a higher minimum wage can, in principle, increase employment in non-competitive labor markets. The key to this result is the difference between competitive labor markets characterized by many competing employers, and non-competitive (monopsonistic) ones, where one or only a few businesses dominate the employment choices of workers. In a competitive labor market firms must pay the prevailing competitive wage to attract workers and can hire as many workers as they want at that wage. Competition among firms ensures that wages stay as high as worker productivity.

By contrast, in markets dominated by only a few firms, attracting additional workers requires raising wages—and not just for new hires, but for existing employees as well. Because this makes expanding employment costly, such firms often choose to keep wages lower and hire fewer workers than in a competitive market, and workers earn less than the value of their production for the firm. In this setting, if a minimum wage is instituted—so that firms have to pay at least that wage to all workers—hiring an extra worker no longer requires raising pay for everyone, so the cost of expanding employment falls. As a result, a carefully set minimum wage can actually encourage firms to hire more workers rather than fewer (although Stigler was very skeptical of policymakers’ ability to calibrate the minimum wage effectively).

Although Stigler was writing about the near-mythical “company town”—where one employer nearly hired everyone—modern economic models can generate monopsony power from different sources. The most common source is labor market “frictions” that tend to bind workers to firms even if another firm is paying a slightly higher wage for a similar job. These frictions, which reduce the rates at which workers find or separate from jobs, can be due to search costs, information frictions, non-wage amenities, or simply the time costs of finding a new job. In such less fluid markets, employers gain wage-setting power not because they are the only firm in town, but because workers’ mobility is limited.

A recent study looking at a narrow retail sector suggests that local labor markets vary in how competitive they are, resulting in positive employment effects of minimum wages in the least competitive ones and near-zero effects in others (with zero or positive effects in roughly two-thirds of markets). This evidence is the basis for the argument that the non-competitive nature of low-skill labor markets can account for findings of zero or even positive employment effects of the minimum wage—and the basis for disputing the usual policy prescription that a higher minimum wage reduces jobs for low-wage workers.

Our recent research shows, however, that this evidence fails to account for the fact that in larger cities, wages are higher and, as a result, minimum wages are binding for fewer workers. Furthermore, larger cities also have less competitive labor markets. Once we account for city size, there is much less evidence that a higher minimum wage can increase employment in less competitive labor markets. Conversely, research that ignores city size leads to considerable exaggeration of how higher minimum wages can boost employment in non-competitive labor markets.

Measuring labor market frictions

In theoretical models of non-competitive labor markets, the key feature reflecting market power over workers is how frequently workers get job offers from different firms. When there are more job offers, it is easier for workers to move between employers and hence firms have less market power over workers—that is, labor markets are more competitive. We therefore use data on job market fluidity—such as hiring and separation rates—to measure how competitive local labor markets are. A more fluid labor market, with higher rates of hiring and separations, is more competitive.

Our data come from the Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI) and Job-to-Job (J2J) datasets, and we use “city” as a short-hand for core-based statistical areas, which consist of one or more counties with an urban core, linked by strong commuting patterns. Our use of fluidity measures differs from past work, which relies on concentration metrics, such as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) or the number of employers per worker. These latter measures stem from the idea that when there are fewer firms competing to hire workers, workers have fewer job opportunities aside from their current employer, which gives employers monopsony power in that labor market. However, despite its use in prior work, concentration can be a poor proxy for monopsony power. In job search models, an increase in the rate at which workers get job offers—which reflects greater labor market competition—can lead to higher concentration as larger, more productive firms attract and retain a disproportionate share of workers, making HHI an invalid measure. Similarly, when there is some differentiation between jobs, firms can be small yet still possess significant power to set wages. Nonetheless, to connect with past work we also show results using concentration measures constructed from the National Establishment Time Series (NETS).

Following recent work that allows the employment effect of the minimum wage to depend on local labor market power, we estimate regression models that capture the overall effect of a higher minimum wage on employment, but also an “interaction” that measures how the effect of the minimum wage varies with measures of monopsony power in local labor markets. We study the United States restaurant industry from 2001 to 2019 using data on employment and earnings from the QWI and state-level minimum wages. The restaurant industry has been the focus of many studies of minimum wages in the U.S. because of the large share of low-wage workers in the industry.

City size, wages, and labor market competition

A key issue for the study of the effects of minimum wage on employment in the U.S. is that researchers may not be able to reliably answer how minimum wage effects vary with local labor market power if other important differences across cities influence the impact of the minimum wage. In particular, wages are higher in larger cities—a phenomenon attributed both to the movement of higher-skilled people into larger cities and higher productivity of workers and firms in more dense areas. It turns out that minimum wages vary less across cities than wage levels, implying that minimum wages will have less “bite” in large cities (they are binding for fewer workers). Previous research on variation in minimum wage effects with local labor market competition has failed to account for this.

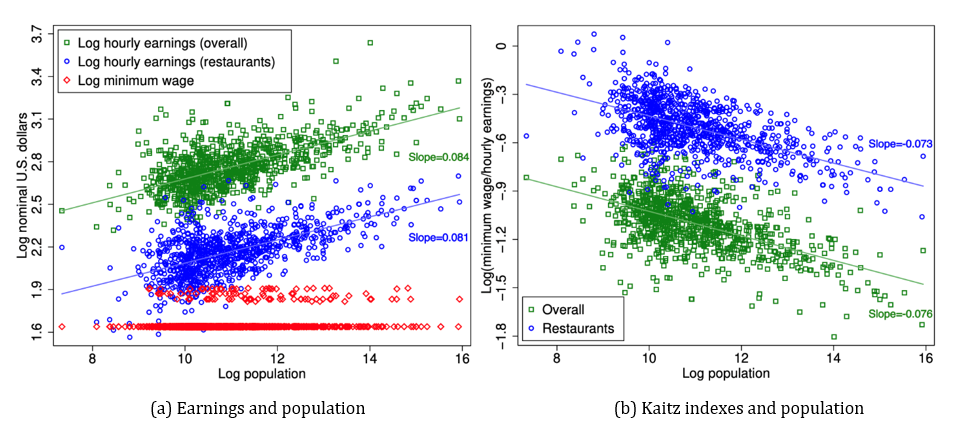

The higher wages in large cities imply that minimum wages, which generally vary at the state level, are less binding in large cities. As shown in Figure 1, there is a strong positive relationship between city size and hourly earnings. In addition, the gap between hourly earnings and the minimum wage is wider, and hence the bite of the minimum wage is lower, in large cities.

Figure 1: Minimum Wages are Less Binding in Larger Cities

We first ignore city size—like the recent research does. When we do this, the evidence suggests that minimum wages reduce employment in more competitive labor markets, but the analysis suggests that there are many markets where labor market power is sufficiently high that minimum wages have no effect on jobs or even increase jobs. We then show, however, that the empirical importance of this variation, and its implications for the employment effects of minimum wages, is overstated in research that ignores city size.

The key fact is that labor market fluidity as measured by our hiring/separation measures is lower in larger cities. (Across the fluidity measures we use, the correlation with log working-age population is always negative and averages −.21.) Because minimum wages are less binding in larger cities (Figure 1), past research may have mistakenly concluded that minimum wage effects in larger cities are weaker or even positive because of labor market power, when in fact all that is going on is that the minimum wage is less binding in these cities. In the latter case, of course, even in the competitive model a higher minimum wage would not reduce employment.

When we estimate models that account for how both labor market power and city size influence the impact of minimum wages, the role of variation in labor market competition is substantially reduced. Even more important, from a policy perspective, is that adverse effect of the minimum wage on employment becomes much more consistent—and consistently negative—across cities. That is, even though we find evidence of some non-competitive labor market behavior after accounting for city size, the new estimates imply that minimum wage effects on employment are generally negative. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Boxplots of Predicted Minimum Wage Elasticities of Employment for CBSA-by-State Entities by Monopsony Power Proxy

Figure 2 illustrates this. The leftmost estimate (for “0” on the horizontal axis), shows the baseline estimated minimum wage elasticity without monopsony power interactions. The vertical figures (“boxplots”) plotted after that point show the estimated median minimum wage effect across cities (the black symbol) and then distributions of estimates, with the thicker line displaying the 25th to 75th percentiles of the estimates, and then thinner lines showing the fuller range of estimates (without outliers). (The symbols on the horizontal axis represent different labor market competition measures and are defined in Table 1 of the paper.)

The left-hand side of the figure is for estimates ignoring city size, while the right-hand side accounts for it. The figure indicates a clear bias against finding job loss from higher minimum wages when ignoring city size (the left-hand side of the figure), as the median estimates are closer to zero, and the ranges of estimates include more positive values. In contrast, the boxplots that account for city size, on the right-hand side of the figure—are shifted down, indicating that even after accounting for monopsony power, minimum wage effects are negative in most places.

Thus, the key result is that estimates that do not account for city size suggest that minimum wage effects are near-zero or positive in many places, which would imply that the effects of minimum wages vary substantively with labor market power. In contrast, once we account for city size—and avoid confounding its effects with those of monopsony power—although minimum wage effects vary, they are negative almost everywhere.

Conclusions

Our research does not say that labor markets are perfectly competitive. Indeed, our evidence that the minimum wage has more adverse employment effects where job market fluidity is higher points to labor markets for low-skilled workers exhibiting deviations from the competitive model. However, minimum wage proponents have over-emphasized the small minority of studies of minimum wages that fail to find job loss, and have latched onto evidence suggesting that there are many local labor markets where deviations from perfect competition imply that a higher minimum wage won’t reduce jobs and may even increase them.

A foundational essay on economics by Milton Friedman argues that the “test” of a model is not whether it is a completely accurate characterization of reality, but rather whether it makes accurate predictions. Our research shows that the evidence does not support jettisoning one of the fundamental predictions of the competitive model of labor markets: that higher minimum wages reduce employment of less-skilled workers.

Authors’ Disclosure: This research was partially supported by the International Center for Law and Economics. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket‘s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket‘s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.