In new research, Damien Capelle and Bruno Pellegrino find that while global capital markets have grown dramatically over the past five decades and reached new jurisdictions, the uneven pace of financial liberalization has failed to reallocate capital to lower-income countries, reduced world GDP by 5.9%, and increased inequality between rich and poor countries.

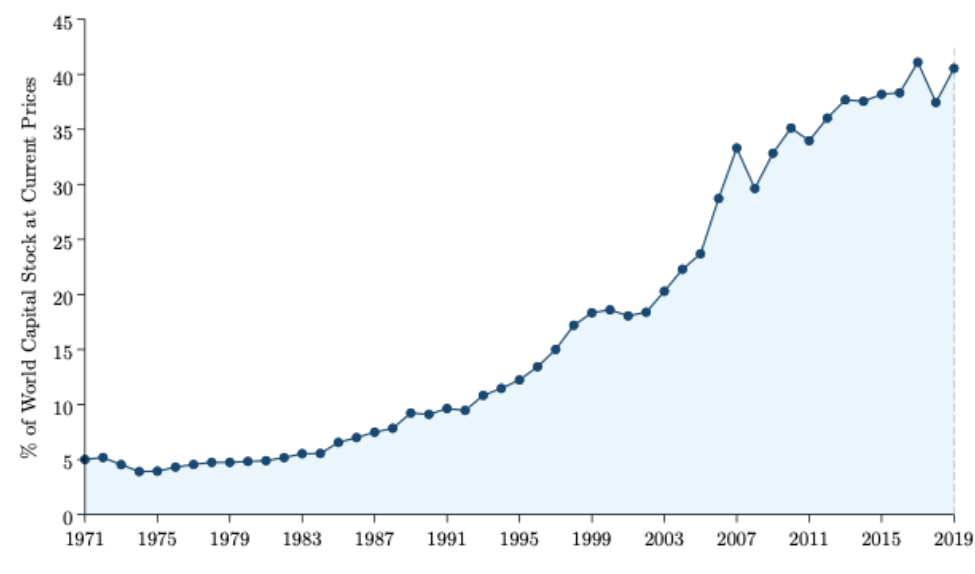

Over the past 50 years, the world has witnessed an unprecedented expansion of cross-border investment. International capital flows have exploded from just 5% of the world’s capital stock in 1970 to nearly 45% today—a phenomenon economists call “financial globalization.”

FIGURE 1: World External Liabilities

A natural question to ask is what were the real implications of these five decades of financial globalization for the global economy? How did it affect world GDP and cross-country inequality? Did it have consequences for where production takes place? In our new paper, we try to answer these questions [link to Stigler WP].

Existing economic models provide some theoretical predictions to these questions: in response to capital market integration, capital should flow from rich countries, where it is abundant, to poor countries, where it is scarce and more productive. These flows should ultimately boost global growth and reduce inequality between nations. Despite these predictions, Nobel laureate and long-time University of Chicago professor Bob Lucas famously observed as early as 1990, in what would be called the Lucas puzzle, that capital does not in fact flow from rich countries to poor countries to level these differences.

In our new paper, we use a dynamic spatial model of international investment and production to study the real implications of the past five decades of financial globalization. We find that financial globalization has been fundamentally “unbalanced”—wealthy countries have opened their doors to foreign investment much faster than poor countries, creating distortions that have actually worsened the global allocation of capital and exacerbated cross-country inequality.

Measuring de facto financial openness

A key insight of our research is that what matters for capital allocation is not whether countries have formally liberalized their capital accounts, but how open they actually are in practice. We make the distinction between countries and policies that are “inwardly” open (able to attract capital) or “outwardly” open (capital escapes easily from the country). Many factors beyond official policy—including political risk, financial development, regulatory quality, and cultural barriers—affect a country’s true attractiveness to international investors.

One challenge in evaluating the real consequences of financial globalization lies in measuring countries’ “de facto” capital account openness. A second challenge is data availability: the data that we would typically use to discipline a model of international investment like ours doesn’t exist as far back as the 1970s, when financial globalization took off in advanced economies. In particular, before the ‘90s, we don’t know the countries’ bilateral investment positions. We only know a country’s overall investment position vis-à-vis the rest of the world.

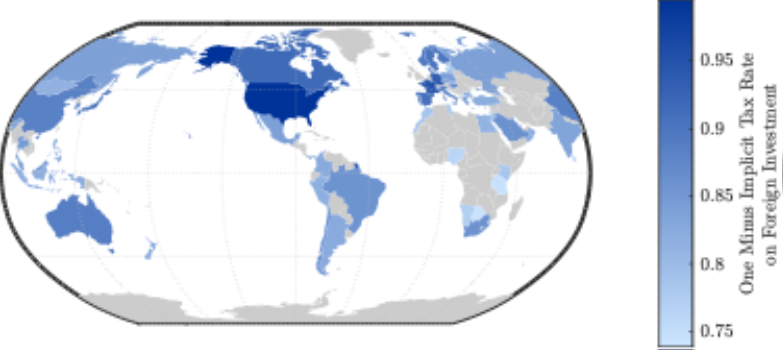

FIGURE 2: RKO Wedges by Country (2019)

To address these challenges, we developed a methodology that leverages our model and publicly available data on countries’ external assets and liabilities to estimate what we call “Revealed Capital Account Openness” (RKO) wedges. We are able to recover these wedges all the way back to 1970 for a large set of countries, covering most of world GDP. These model-based measures effectively capture the implicit tax rate that investors face when investing across borders, summarizing all the various frictions and barriers like political risk, capital controls and regulatory quality, that impede international capital flows.

We validate our RKO wedges in several ways. First, we show that they align well with known barriers to international investment—such as political risk, weak institutions, or capital controls. Second, we examine episodes when countries liberalized their financial markets—for example, by removing restrictions on foreign investors or allowing domestic firms to raise funds abroad. We find that our measure of “Revealed Capital Account Openness” increases after such reforms, just as it should. These episodes are important because they provide a real-world test of whether our measure captures meaningful changes in how open a country actually is to international capital.

The unbalanced nature of financial globalization

When we analyze our RKO wedges over time and across countries, a striking pattern appears. While all countries have indeed become more financially open over time—the average implicit tax on international investment has fallen from 27% in 1971 to 17% in 2019—this opening has been highly asymmetric.

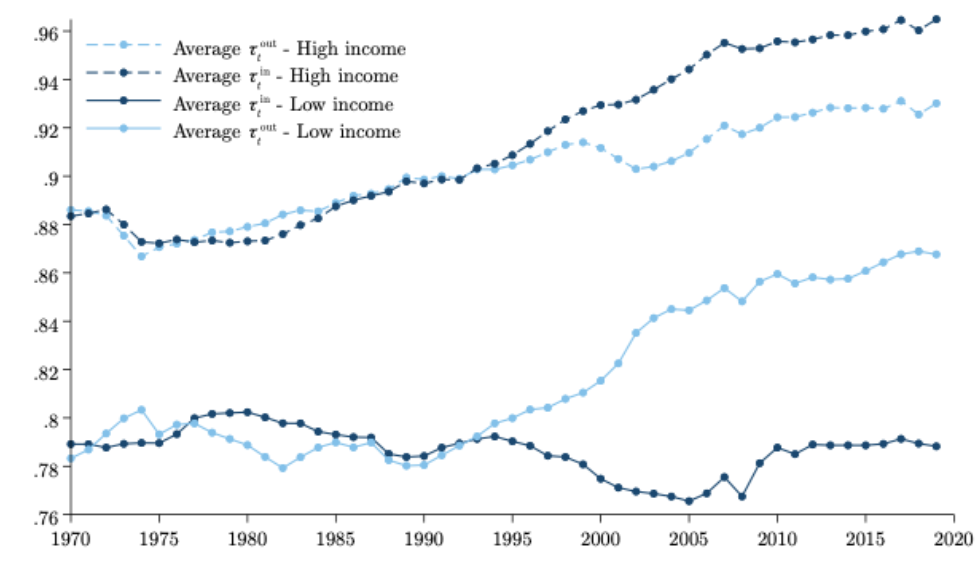

FIGURE 3: Revealed Capital Account Openness (τ), by income group and direction

High-income countries have opened much faster to capital inflows than low-income countries. Meanwhile, low-income countries have primarily opened to capital outflows rather than inflows. This creates a fundamental imbalance: the countries that already had abundant capital became even more attractive to international investors, while capital-scarce countries remained relatively closed to foreign investment but became more prone to capital flight.

Figure 3 reveals this pattern clearly. The implicit tax rate on capital inflows in high-income countries plummeted from 11% to just 4% over the past 50 years. In contrast, for low-income countries, this rate has remained stubbornly around 21%. On the outflow side, both groups have converged—high-income countries reduced their outflow barriers from 11% to 7%, while low-income countries cut theirs more dramatically from 22% to 14%.

The economic implications of unbalanced openness

Using our model to simulate counterfactual scenarios, we find that this unbalanced pattern of financial opening has had profound economic consequences. Rather than improving global capital allocation as traditional theory would predict, unbalanced financial globalization has actually made it worse.

Our central finding is striking: world GDP in 2019 was 5.9% lower than it would have been had financial globalization never occurred. This represents a massive efficiency loss—nearly $6 trillion in lost global output. The mechanism is straightforward but counterintuitive: because wealthy countries opened faster to capital inflows, they attracted even more investment despite already having abundant capital and low returns. Meanwhile, capital-poor countries with high returns remained relatively inaccessible to foreign investment, and it became easier for capital to “escape” these countries. In other words, differences between high- and low-income countries in the pace and direction of liberalization exacerbated existing differences.

The distributional consequences are equally stark. Inequality between countries, as measured by the variance of GDP per capita, is 3.4% higher than it would have been without financial globalization. This unbalanced opening has created a world where capital flows uphill—from poor to rich countries—exactly the opposite of what economic theory predicts should happen.

Within countries, the effects vary dramatically by income level. In high-income countries, wages are 3.4% higher than they would have been without financial globalization, reflecting the higher capital-to-labor ratios resulting from capital inflows. But in low-income countries, wages are 9.8% lower, as capital scarcity has been exacerbated by the relative ease of capital outflows compared to inflows.

What if globalization had been balanced?

When we compare our findings to the existing literature in international macroeconomics, they will strike many readers as deeply counterintuitive. For a skeptical observer, it is natural to suspect that, among its many moving parts, our model could hide some unorthodox feature that makes financial globalization inherently “bad.”

However, we can show that our model is not unorthodox in how international financial integration affects the distribution of capital. What leads to these surprising effects is not financial globalization per se, but rather its unbalanced nature.

To make this point, we simulate two alternative scenarios where opening occurred more symmetrically across countries. In a “symmetric” scenario where all countries opened at the same pace and in the same direction (while maintaining their initial differences in openness), world GDP would have been 5.7% higher than without any globalization. In a “convergent” scenario where all countries gradually converged to the same level of openness by 2019, world GDP would have been an astounding 23.6% higher. In other words, under this “balanced” scenario our model behaves like a traditional model, and financial globalization has all the consequences a neoclassical economist would expect. This in turn confirms that it is the asymmetry that has characterized financial globalization and that drives these results.

These counterfactuals reveal large potential gains from more balanced financial globalization. In both scenarios, capital flows from rich to poor countries as theory predicts, boosting global efficiency and reducing inequality. In the convergent scenario, wages in low-income countries would have been 69% higher, while inequality between countries would have been 24% lower.

Takeaways for economists and policymakers

Our findings underscore the crucial importance of modeling what economists call “spatial heterogeneity”: namely, the many ways in which places or countries differ from each other. The way international macroeconomists have previously modeled capital account integration is plagued by the implicit, counterfactual assumption: that countries will liberalize in a symmetric way, or in a way that will reduce their pre-existing asymmetries in capital account openness.

A strength of our modeling framework that sets it apart from the previous literature is how it leverages all available data to capture these country differences. These differences matter a lot. In particular, we learned that differences in the pace and direction of de-facto openness can be so important as to completely undo the beneficial effects of financial globalization.

These insights have important implications for international financial institutions and policymakers. Our results suggest that the sequencing and coordination of capital account liberalization across countries can have profound effects on global efficiency and equity.. Uncoordinated reforms risk worsening imbalances rather than correcting them.

Our findings also highlight the importance of addressing the underlying factors that make some countries less attractive to foreign investors, including weak institutions, political instability, and underdeveloped financial markets. Simply removing formal capital controls may not be sufficient if these deeper structural barriers remain in place.

Authors’ Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Author’s Note: Damien Capelle is an economist for the International Monetary Fund. This article represents the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the IMF or its management, executive board, or member countries.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.