In new research, Petros Boulieris, Bruno Carballa-Smichowski, Maria Niki Fourka and Ioannis Lianos analyze industrial policy from around the world to understand how policymakers are rethinking policy goals. The authors create a set of metrics to measure how different policy orientations improve or sacrifice competition.

Following a period in which competition and industrial policy evolved in isolation from each other, recent consensus has emerged that they are not inherently incompatible. This shift reflects broader intellectual changes, with industrial policy now viewed more favorably and designed not only to achieve traditional development goals, but also to enhance technological capabilities for national security and to secure dominant positions in the global economy.

In a new paper, “New Industrial Policy Design and Competition: A Computational Approach,” we analyze industrial policies from around the world to understand their goals. We group them into three types—traditional techno-nationalism (seeking developmental targets), new techno-nationalism (motivated by security reasoning and global economic supremacy), or techno-globalism (pursuing global sustainable development goals)—and evaluate how they align with different metrics of competition. Our findings shed light on current modes of economic thought and pave a pathway for policymakers to invest in national industry without sacrificing competition.

The view from Europe

The debate over the compatibility between competition and industrial policy is perhaps nowhere livelier than in Europe. Critics see active enforcement of competition law in Europe (and elsewhere) as an obstacle to implementing an effective industrial policy and to the development of nascent national or European champions by, for example, restricting state aid or aggressively preventing efficiency-enhancing mergers. From an economic evidence for the “infant industry” approach that argues inchoate industries and firms require protection from competition remains quite ambiguous, the hypothesis working only in very specific circumstances. In contrast, there is significant evidence that competition policy and competition law enforcement enhances the developmental potential of an economy. Recent empirical evidence from the United Kingdom shows that “market power (as measured by firms’ cost markups) and industry concentration do not seem to change in response to observed industrial policy changes,” suggesting that “industrial policy and competition policy are not necessarily in conflict.” It is also widely accepted that competition promotes institutional innovation and the emergence of efficient institutions that support economic growth. There is now empirical evidence that competition law enforcement and competition policy is linked to economic growth in developed countries.

However, in the era of the entrepreneurial state and a mission economy, competition policy is also about shaping markets to enhance competitiveness. Former President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi’s approach to competition policy, articulated in a much-debated report released last fall, represents from this perspective a departure from conventional competition law and economics thinking. Throughout various horizontal and sectoral chapters of the report, Draghi recognizes the crucial role of competition policy. However, he notes that in an economy characterized by increasing returns to scale, network effects, and feedback loops, as well as growing dependence on dominant designs in the evolution of technological trajectories, competition law must evolve. Competition law should also foster productivity, growth, and the generation and diffusion of innovation, while incentivizing significant public and private investments. This vision is shared by the European Commission, which recently published its Competitiveness Compass, a roadmap for improving European dynamism and growth.

The emerging consensus is that there is not necessarily an incompatibility between competition and industrial policy, and there is ample room for a “pro-competitive industrial policy.” The broader intellectual environment has also changed since the 1980-2009 neoliberal consensus. There is now a more positive stance on industrial policy, not only for the traditional developmental purposes but also to promote technological capabilities for national security or, more broadly, to maintain a dominant position in the global economy. Indeed, in recent years, competition law has evolved towards a more “polycentric approach,” wherein competition enforcement serves as a vehicle for broader, non-strictly economic objectives, such as strengthening global supply chain resilience or facilitating the green transition.

The manifold goals of industrial policy

Industrial policies can be described in terms of the goals they pursue as falling within one of the following three broad categories. Traditional “techno-nationalist” industrial policy seeks pure developmental goals, such as reindustrialization or expanding the technology sector. The new version of techno-nationalism mostly focuses on promoting realist goals of national security or global economic supremacy. Techno-nationalism may enter into tension with the pursuit of resolutions to global challenges. For example, a policy that prioritizes national innovation, startups, and champions through selective enforcement patterns over the diffusion of green technology from other countries may hamper the fight against climate change. The underlying aim of such approaches is to secure technological sovereignty (or “techno-sovereignty”).

The third type of industrial policy, “techno-globalism,” pursues goals that are to the benefit of global welfare.Techno-nationalist approaches to industrial policy may conflict with industrial policies promoting technology diffusion efforts addressing global issues like climate change (an example of techno-globalist industrial policy).

Competition law also may be viewed through a “techno-globalist” lens that concomitantly targets global public goods. For example, a nation can target the global market power of digital platforms to enhance global (including) consumer welfare, even if this at the expense of techno-nationalist industrial policies.

These developments require a more thorough and empirical analysis of the interaction between competition law and industrial policy and a better understanding of the various rationales for adopting industrial policy interventions, particularly since the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent resurgence of industrial policy interventions. The literature on the intersection of competition policy and industrial policy is already grounded in empirical analysis. However, given the novelty of new industrial policy interventions post-Covid, we lack evidence on how new industrial policy in general, and techno-nationalist and techno-globalist industrial policies in particular, interact with the goals of competition policy.

Our article, “New Industrial Policy Design and Competition: A Computational Approach” makes a contribution in that direction by providing an empirical analysis through the use of large language models (LLMs). Drawing on 2,500 entries in the New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO) database, which tracks government interventions to support local firms and sectors, we study the pro- and anticompetitive features of “new industrial policy” between July 2020 and December 2029 across 76 jurisdictions. This analysis included comparisons between techno-globalist and techno-nationalist approaches based on 15 benchmarks of pro- or anticompetitiveness (for example, number of competitors, interventions providing a competitive advantage, ex ante conditionality of industrial policy intervention on local content or production, or interventions reducing entry costs).

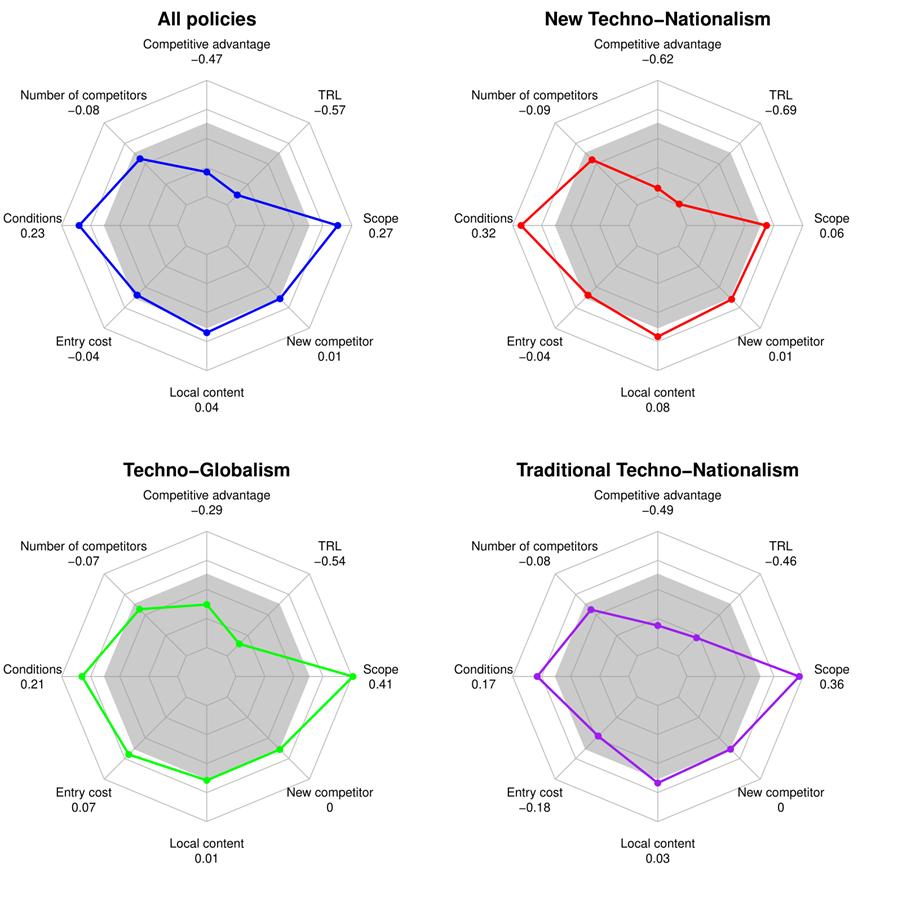

In summary, we find techno-globalist industrial policies are generally more procompetitive than techno-nationalist ones, though important distinctions exist among different forms of techno-nationalist policies. The figure below summarizes how pro- or anticompetitive each type of industrial policy is in the eight dimensions identified.

Synergies, trade-offs and neutral grounds

There is no straightforward link between competition policy goals and new industrial policy design. By attaching conditions (e.g., meeting green targets to secure a subsidy) and having a broad scope (i.e., targeting multiple industries or many firms in the same industry), new industrial policies tend to foster procompetitive outcomes. Yet, they also lean towards anticompetitive outcomes by favoring established technologies and incumbents. This is true for all three industrial policy types.

Other policy design features discussed in the literature occur infrequently—such as those affecting entry costs, local content requirements, or facilitating the emergence of a new competitor. When these features are common, as in the case of the number of competitors targeted, they do not show a clear bias towards either pro- or anticompetitive outcomes.

Regional industrial policy approaches

Approximately all industrial policies fall into the three descriptive categories of techno-globalist, new techno-nationalist, and traditional techno-nationalist, with each category accounting for a third of these policies. In China, new techno-nationalist industrial policy predominates: they constitute 70% of the observations. In the EU, techno-globalist policies represent close to half of the observations (48%), followed by new techno-nationalist policies (34%). The U.K. seems to follow a predominately new-techno-nationalist industrial policy (more than 54% of the observations), followed by techno-globalist (23%) and traditional techno-nationalist (21%) industrial policy interventions. In the United States, the share of traditional techno-nationalist policies is particularly high (38%) and close to the share of new-techno-nationalist ones (41%).

This notable difference between the EU pursuit of techno-globalist policies and the preference for techno-nationalist policies in other jurisdictions may stem from the gradual erosion of “national industrial states” across Europe over recent decades. This erosion likely stems from the EU’s post-1980s prioritization of the establishment of the internal market and its commitment to ordoliberal competition principles, both emphasizing the liberalization and opening of European markets to enhanced competition.

Techno-globalist policies exhibit a procompetitive profile primarily because they tend to have a wider scope and lower entry costs. However, they also tend to favor incumbent firms more than average. Traditional techno-nationalist policies score better than the average in terms of their scope (although less than techno-globalist ones), and in that they target less-mature technologies. Nevertheless, they are less likely to include conditions (e.g., meeting an export target to benefit from a subsidy), and they increase entry cost more frequently. Finally, new techno-nationalist policies are procompetitive to the extent that they incorporate conditionalities more often than other types. Yet, they also display anticompetitive tendencies by targeting mature technologies, having a narrower scope (e.g., focusing on specific firms) and favoring incumbents.

The drivers of pro- and anticompetitive policy design

Our analysis indicates that the adoption of certain policy instruments is correlated with the presence of some pro- and anticompetitive design features. The use of trade and finance instruments, import policies, localization measures, and capital injections (including equity stakes) is linked to a higher likelihood of anticompetitive outcomes. For example, if an industrial policy includes an import policy, it is 5.5 times more likely to benefit an incumbent than if it does not. This is due to the fact that import policies tend to protect local incumbents against foreign competition. In contrast, instruments such as sanctions, import tariffs, and public procurement localization tend to promote procompetitive outcomes by targeting multiple sectors rather than specific firms.

Additionally, the underlying policy motives and the level of application matter. Policies invoking geopolitical concerns or national security tend to be more anticompetitive, while supra-national policies generally favour incumbent firms. Conversely, sub-national policies are less likely to increase entry costs.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that current geopolitical tensions have catalyzed a profound revival of state interventionism and industrial policy, now strategically oriented toward securing competitive advantages in an increasingly fluid global landscape characterized by shifting diplomatic and economic alliances. This environment often creates the temptation to implement interventions without fully considering their competitive implications—a shortsighted approach that undermines economic growth potential and produces significant social and distributional consequences, given competition policy’s essential role as a regulatory instrument maintaining systemic resilience.

A new political economy vision of industrial policies will also acknowledge that industrial policies should aim to “firstly, orient the rate and direction of technical change; secondly, govern and shape the direction of collective answers to major challenges; [and] thirdly, promote alliances beyond different and possibly conflicting interests, bringing together actors and institutions with the ability to undertake social coordination at the benefit of society.” A more nuanced and targeted analysis of these interactions would enable public authorities to allocate their constrained resources more effectively toward assessing the welfare and broader geo-economic impacts of truly contentious industrial strategies, thereby substantially enhancing governance quality in today’s emerging “Industrial State” paradigm. This analysis would include examining specific categories and criteria of industrial policy interventions, such as a global value chain perspective that assesses the possibilities of economic (industrial) and social “upgrading” of domestic stakeholders. Our article makes a contribution in that direction by using AI to better assess the techno-globalist or techno-nationalist nature of industrial policies interventions and of their possible interaction with competition policy norms.

Authors’ Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Author’s Disclaimer: Bruno Carballa-Smichowski works for the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. The opinions expressed in this article represent his personal views and are not the opinions of the Joint Research Centre or European Commission.

Author’s Disclaimer: Ioannis Lianos is Professor of Global Competition Law and Public Policy and co-Director, Centre for Law, Economics and Society, UCL Faculty of Laws. He is also a Member of the UK Competition Appeal Tribunal. Any views expressed in this article are strictly personal.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.