Despite individual investors being strongly divided on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues, corporate policies are largely determined by large institutional investors that adopt predominantly moderate ESG stances. In new research, Nicola Persico and Enrichetta Ravina explore this disconnect by examining the mechanisms driving the moderate ESG positions of major financial institutions and investigating potential impacts of allowing individual investors to select their own proxy voters.

In contemporary America, many consequential societal choices like environmental policies, executive compensation, human rights, gender equality, privacy protections, and product safety standards are increasingly determined not by legislative bodies but by corporate decision-makers responding to shareholder directives.

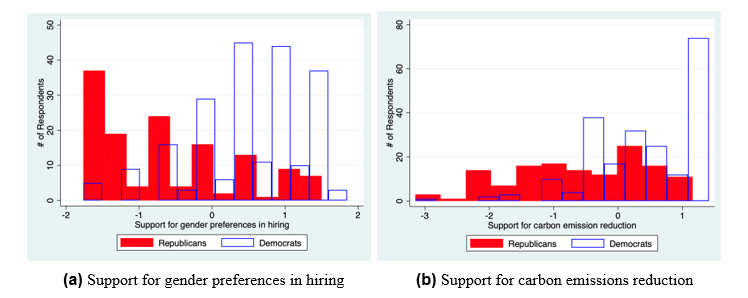

Individual investors are strongly polarized on such issues, which form the constituent parts of the “environmental, social, and governance” (ESG) framework. In our new paper, “ESG Choice with Polarized Investors,” a survey we run on Prolific shows that self-identified Democrats (below, the hollow blue bars) are much more likely than Republicans (solid red bars) to support corporate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and climate emission reduction policies (Figure 1). These findings are supported by several studies showing polarization within many occupations and among company executives and directors.

Figure 1. Individual investors are polarized on ESG

Yet, for large public firms, corporate policies are primarily determined not by individual investors but rather their large institutional investors, which have predominantly adopted moderate ESG stances. Measures of investment funds’ ESG orientations, based on asset managers’ voting behavior in the companies’ shareholder meeting, show that the large fund families (Fidelity, Capital Group, State Street, Vanguard, and BlackRock) are in the middle of the fund distribution, while the smaller fund families (e.g., Domini and Needham) are at the extreme (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Large funds are moderate, small funds are polarized

These centrist positions of the large institutional investors have been politically costly and have attracted backlash both from the left for not doing enough ESG and from the right for doing too much of it.

Economic mechanisms driving large funds’ moderation

So why do large funds prefer moderation on ESG issues even if moderation is politically costly? In our paper, we explain this phenomenon by examining how profit-maximizing financial institutions compete for investments.

In our model, individual investors care about both financial performance and the level of ESG implemented by the firms they invest in. For analytical clarity, we categorize these individuals into two types: type A, who favor strong ESG policies, and type B, who are indifferent, skeptical, or actively opposed to such policies.

Within this framework, profit-maximizing financial institutions compete to attract investments and maximize fee revenue. However, the competitive dynamics differ substantially between small and large funds.

Smaller funds operate in competitive markets with lower barriers to entry. To attract investors, these funds target either type As or type Bs by offering customized portfolios and voting policies that cater to their specific ESG preferences.

By contrast, large funds benefit from significant populations of “captive” retirement-plan investors and others facing high switching costs, partially shielding the funds from full competition. To maximize assets under management and fee revenue, these funds implement centrist portfolio, voting, and engagement policies that represent a compromise between the preferences of polarized investor types, so as to attract and retain as many investors as possible across the political spectrum. This approach, while boosting fee revenue, produces corporate governance outcomes that fail to match the preferences of individual investors, or maximize the welfare of society.

Given the market dominance of large funds, their preferences disproportionately influence ESG implementation across the universe of U.S. public companies.

Alternative voting mechanisms and their implications

The misalignment between institutional voting patterns and individual investor preferences has prompted some investors and politicians to call for reforms that transfer voting power back to individual investors.

We explore three alternative voting approaches:

Direct Individual Voting: our model predicts that in a one-share-one-vote system, where individual investors cast votes directly, ESG levels would likely become more polarized—either high or low—depending on company characteristics and the relative ownership size of different investor types. Since a company’s ESG levels depend on the relative ownership shares of different investor types, and the number of shares each type purchases depends on the levels of ESG they expect to see implemented, share ownership and ESG levels are simultaneously determined. This dynamic can generate multiple equilibria in some cases, where outcomes could tip in either direction depending on investor expectations. When multiple equilibria are possible, company management or large institutional investors might have incentives to influence outcomes toward their preferred results through various signaling mechanisms.

A practical limitation of this voting system is that individual investors typically lack the time, expertise, and interest to vote on thousands of corporate proposals annually, many of which involve complex technical or industry-specific considerations.

Current pilots by major funds: The “Big Three” (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street) are testing systems where participants select from general investment policies that funds implement on their behalf when deemed appropriate. However, participation rates remain low: around 2% of eligible investors. This limited engagement suggests that a more robust mechanism may be needed to meaningfully align corporate governance with individual investor preferences.

Representative delegation model: We also consider a mechanism resembling representative democracy, where individual investors delegate their votes to trusted entities aligned with their values—politicians, large investors, union leaders, public figures, or fund managers. Investors would select representatives when opening accounts and retain the option to change their delegation periodically. The default for those not making a choice is that the shares are voted by the fund.

In our model, these political entrepreneurs compete for individual investors’ proxies much as politicians compete for votes—by campaigning on values, priorities, and specific governance positions. We already observe nascent versions of this approach in the increasingly political public communications of prominent investors and CEOs, who use social media and other platforms to signal their positions on contentious issues.

For example, Bill Ackman has used X (formerly Twitter) to comment on ESG and DEI policies at Harvard University and to endorse political candidates. Howard Schultz, former Starbucks CEO, has been vocal on healthcare, race relations, and immigration. Marc Benioff, Salesforce CEO, has actively opposed religious freedom laws in states like Indiana. New entrants like 1789 Capital (whose board includes Donald Trump Jr.) and Vivek Ramaswamy’s Strive Asset Management explicitly position themselves as alternatives to mainstream funds on social and political grounds.

Our model indicates that a delegation mechanism would inject greater contestability into corporate governance, potentially leading to more expensive and high-profile corporate campaigns but generating higher individual investor engagement. The resulting ESG levels would more accurately reflect the preferences of underlying investor populations, though outcomes would vary based on share ownership and delegation patterns across different firms. Notably, large funds’ moderate stance would still prevail at those firms where they remain the median voter despite their diminished voting power, but this moderation would be less pervasive than under the current system.

In conclusion, our research explains the institutional constraints and incentives driving large investment funds’ moderate ESG stances while exploring voting mechanisms that would return voting power to individual investors. While such mechanisms would likely create more polarization in corporate policy, they would also make corporate governance more contestable and potentially more responsive to investor preferences.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.