In new research, Michele Fioretti, Victor Saint-Jean, and Simon Smith show that NGO activism follows a clear economic logic: when NGOs lack visibility, stakeholders do not view them as credible, forcing them to rely on high-profile campaigns during annual shareholder meetings. However, these actions generate attention but rarely influence decisions. As NGOs gain recognition, they can campaign earlier, when votes are still open, and meaningfully sway shareholders and change corporate behavior.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are often seen as moral watchdogs that pressure companies to improve their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices through public campaigns. These efforts range from grassroots consumer boycotts—such as the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ push for fair labor standards at major retailers—to high-profile advocacy like Greenpeace’s 2015 “McAmazon” campaign linking McDonald’s to Amazon deforestation. Yet the logic behind how NGOs choose and time these actions remains a black box. We rarely ask how NGOs—especially young ones—build the influence needed to change firm behavior.

Our new study shows that early-stage NGOs focus first on gaining visibility rather than directly shaping corporate decisions. When lacking credibility with investors, even well-intentioned campaigns cannot sway shareholder votes or corporate policy. Publicity, therefore, becomes the primary objective.

This helps explain why emerging NGOs often target companies during annual shareholder meetings (AGMs), when firms face intense public scrutiny. These actions generate attention but rarely affect outcomes. As NGOs become more established, however, they shift their campaigns to precede these meetings—when votes are still undecided and negotiation is possible. Only then do their efforts meaningfully influence shareholder support and corporate behavior, especially in companies with a moderate level of shareholder concentration.

These patterns reveal that the timing of an NGO’s campaign is designed to mobilize different stakeholders, including journalists, retail investors, and senior management, who each have distinct preferences and leverage over firms. As a result, whether and when companies internalize ESG demands depends not only on the specific issue at stake and its financial and operational feasibility, but also on the strategic intention of the NGO activist: whether it is building influence to inform and coordinate shareholders’ votes through exposure or has already secured the influence necessary to inform shareholders how they should vote and coordinate them accordingly.

AGMs as visibility engines

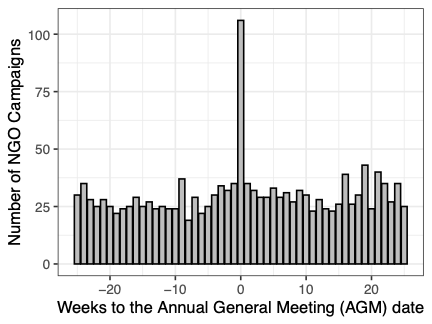

Our analysis begins with a striking empirical pattern. As shown in Figure 1, NGO campaigns are five to six times more likely to occur in the week of a firm’s annual shareholder meeting than in other weeks, and media attention to the targeted firm peaks at the same time.

Figure 1. Campaigns Peak at Annual Meetings, Along with Media Attention

This alignment is no accident. Annual meetings attract journalists, investors, and senior executives, and are accompanied by corporate disclosures that invite scrutiny. For NGOs seeking public visibility, AGMs offer a predictable moment when attention is both concentrated and diverse.

These campaigns succeed in raising visibility. Search activity for the NGO increases, negative media coverage of the targeted firm rises, and younger NGOs—those still building name recognition—experience meaningful boosts in donations. But despite these gains in attention, AGM-timed campaigns do not influence the outcomes that matter most for corporate governance. Because most shareholders vote by proxy well before the meeting, votes are largely decided by the time the AGM takes place. Consistent with this institutional constraint, we find no effect of AGM-day campaigns on vote shares or proposal success. AGM actions shape the public conversation, not the decision.

This gap between visibility and influence helps explain how NGO strategies evolve over time. Early in their organizational life, NGOs lack both credibility and recognition. For them, AGM-day campaigns are an efficient way to build awareness: they are inexpensive, predictable, and timed to moments of heightened scrutiny.

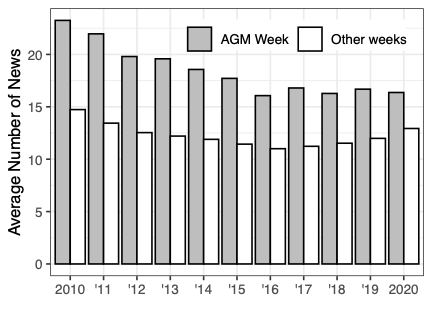

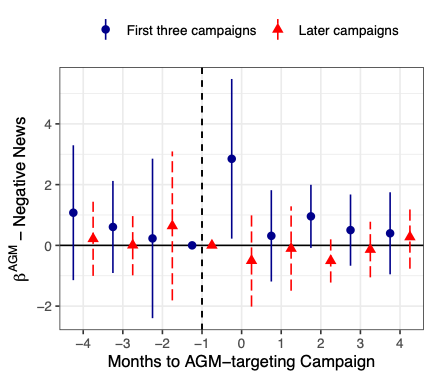

Figure 2 illustrates this dynamic. During an NGO’s first few campaigns, AGM-day actions generate large spikes in online searches for the NGO and sharp increases in negative media coverage of the firm. Later in the NGO’s life, the same actions produce little additional visibility, reflecting diminishing returns as name recognition grows.

Figure 2. Search Activity and Media Coverage Jump for Early-Stage NGOs’ Meeting-Day Actions

As visibility accumulates, NGOs shift away from AGM-day campaigning. Instead, they target firms earlier in the shareholder meeting cycle, when votes are still open and influence is possible. The models in the paper formalize this transition: NGOs initially invest in highly visible AGM actions to build awareness, then move to earlier, costlier campaigns that build credibility and affect outcomes. The result is a clear lifecycle of NGO engagement—exposure first, influence later.

Influence happens when votes are still in play

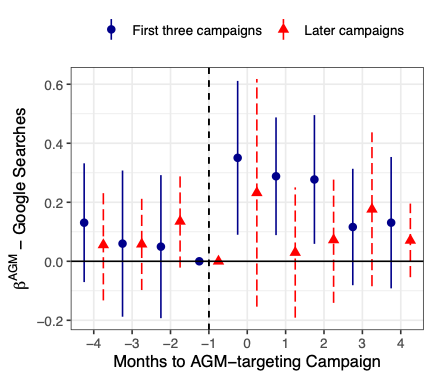

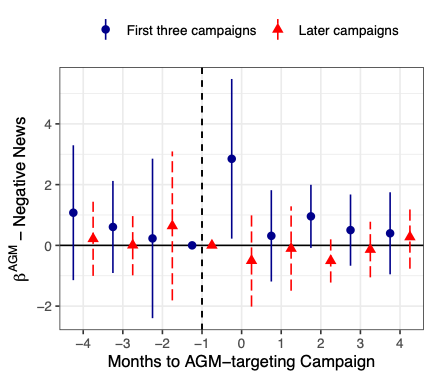

If NGOs want to affect ESG outcomes, they must act before shareholders submit proxies. When they do, the effects—unlike those of AGM-day campaigns—are visible and substantive.

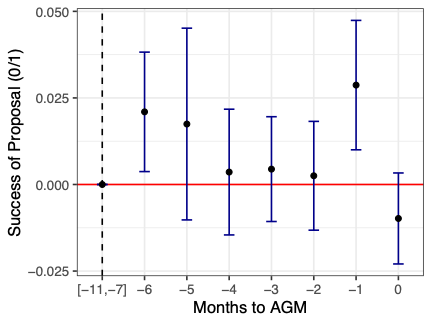

Campaigns launched one to three months before the AGM increase the likelihood that related ESG shareholder proposals succeed and raise support when proposals go to a vote. The left panel of Figure 3 shows this pattern clearly: campaigns between one and three months from the AGM generate an additional 8% share of the vote in support of ESG.

Figure 3. Shareholder Support Rises When NGOs Campaign Ahead of Annual Meetings

Earlier campaigns can influence outcomes indirectly. Actions taken about six months before the AGM, while too early to affect votes as proposals have not been casted yet, increase the rate at which proposals are withdrawn after firms reach settlements with shareholders (right panel). This pattern suggests that NGOs play a role in facilitating or accelerating negotiations between shareholders and management.

The study also finds effects on firm behavior beyond the vote itself. Firms targeted by pre-AGM campaigns, especially those undertaken by reputable NGOs, exhibit measurable improvements in ESG performance in the following year, which is consistent with the idea that the target firm took actions to consider the NGO demands. These gains do not appear after AGM-day campaigns, reinforcing the distinction between visibility and influence.

Stakeholders respond to different campaign timings

The model clarifies why NGOs behave so differently at different stages of their life. NGOs can influence firms only if shareholders view them as credible coordinators—actors capable of sustaining pressure and helping investors align on an issue. But credibility is not automatic. When an NGO is still unknown, shareholders expect it to be ineffective, which means its actions cannot sway votes. In this setting, even well-intentioned early campaigns fail to reveal anything useful about the NGO’s toughness or competence.

The only rational strategy for an NGO still building credibility is therefore to pursue visibility, not influence. AGM-day campaigns deliver immediate exposure because firms face unusually concentrated media and investor attention, even though votes are already cast and nothing can be changed. These actions build the awareness the model identifies: they make stakeholders notice the NGO, but do not update beliefs about its effectiveness.

As visibility accumulates, the incentives flip. Now early campaigns become informative because they occur when shareholder decisions remain open. If an NGO mobilizes support or contributes to a settlement, investors update their beliefs upward, raising the NGO’s credibility. In equilibrium, NGOs shift from visibility-seeking to credibility-building tactics, and only then do their campaigns reliably influence corporate outcomes.

How shareholder concentration impacts NGO influence

We also find that the effectiveness of NGO campaigns in increasing the filing and success of related shareholder proposals, as well as subsequent improvements in firms’ ESG performance, depends on firms’ ownership structure. Campaigns are less effective when ownership is highly concentrated. Since the vast majority of proposals on social and environmental issues are filed by small shareholders, firms dominated by single large shareholders are harder to influence as they have easier access to management and control a large share of votes. Similarly, when ownership is extremely dispersed and free-riding is severe, it becomes harder to organize shareholders. Instead, campaign impact is strongest at firms with intermediate levels of concentration, where dispersed investors face meaningful coordination frictions but collective action remains feasible.

Additional evidence reinforces this interpretation. AGM-timed campaigns predict new shareholder proposal filings only in firms with intermediate ownership concentration, while the marginal effect of early campaigns on proposal success declines with higher and lower levels of concentration. Moreover, proposals in the data are typically filed by small shareholders rather than pivotal blockholders, further suggesting that NGO campaigns operate by aligning dispersed investors rather than persuading a small set of decisive owners or a wide range of misaligned shareholders.

Conclusion

Taken together, the results indicate that NGO credibility enhances influence by publicizing and making ESG proposals acceptable. They also suggest that credible NGOs can help coordinate shareholders’ interests, complementing formal shareholder rights and regulatory oversight. Campaign timing therefore shapes not only visibility, but also which stakeholders become collectively relevant for firm decision-making.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.