In recent research, Yumin Hu, Luca Macedoni, and Mingzhi Xu explore how high income inequality can raise the costs of living. They compare grocery products around the U.S., finding that large retailers will increase the prices for their goods in places where income inequality is also high.

Is it more expensive to live in a county where income inequality is high or in one where most households have similar incomes? The short answer is: it depends on what you buy. In new research, we use barcode-level data on identical grocery products sold across United States counties—and a parallel exercise with Chinese exporters—to find that prices don’t move uniformly when inequality rises. Instead, the direction of the change depends on the product’s market size, or how many people could potentially buy a product. As inequality increases, prices tend to fall for goods with small market shares, like non-essential and luxurious items, and rise for those with large market shares, such as essential grocery and household products. Because large firms earn most of their revenue from these high-share goods, inequality tends to raise their average prices, while smaller firms often move in the opposite direction.

The price cost of unequal incomes

Our evidence comes from the NielsenIQ Homescan Consumer Panel, which tracks what American households bought—barcode by barcode—from 2004 to 2018. This unique dataset lets us follow the exact same product—say, a 12-ounce cereal box or a specific brand of shampoo—across thousands of counties and retailers. That level of detail matters: it allows us to compare apples with apples and strip out everything else that could move prices, such as production costs, store policies, or brand-specific promotions. What’s left captures how markups change on identical goods sold in different local markets.

We then connect these barcode-level prices to local inequality, using standard measures such as the Gini index along with income and population data. The key question is simple: do products with high market shares react differently to rising inequality than the ones with low market shares? To find out, we fix each product’s initial market share at the start of the period and see how its price responds as inequality changes.

The pattern is striking and consistent. As inequality rises, prices fall for low-market share goods but rise for high-share goods. Most products show little movement, yet the items that dominate household spending—everyday staples and big brands—become noticeably more expensive. In numbers, a one-standard-deviation increase in local inequality raises prices of high-share products by roughly 1–2 percent and lowers prices of low-share products, with a small but positive average across all goods. To give a sense of scale, this effect on product prices is about 40 percent as large as the impact of a comparable rise in per-capita income. The average effect may look modest on paper, but because it falls on the goods people buy most often, the overall impact on the cost of living is meaningful.

How inequality fuels big firms’ pricing power

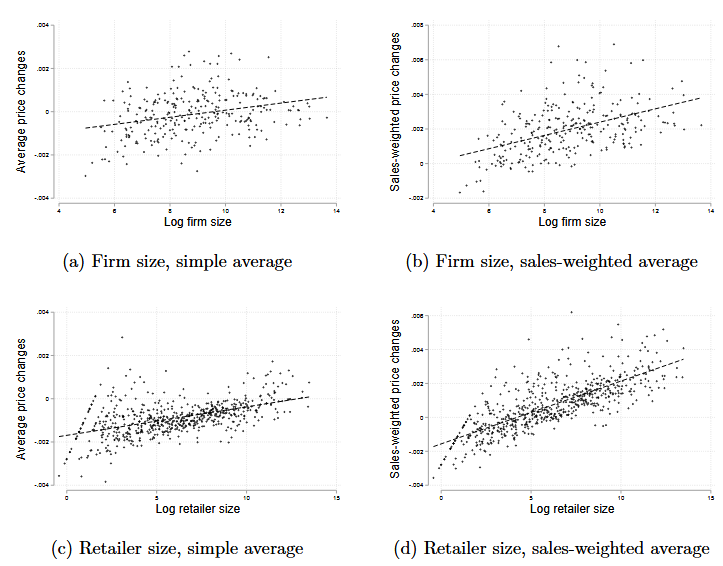

When we look beyond individual products to the firm and retail-chain level, a clear pattern emerges: bigger players raise prices more when inequality grows. Sellers whose sales are concentrated in large-market-share products tend to show higher average prices in more unequal markets, while those selling relatively more small-market-share products move in the opposite direction. Figure 1 shows this relationship: it plots the average price change from a one–standard–deviation increase in inequality in 2004, distinguishing between firm size (top panels) and retailer size (bottom panels). The left panels show simple averages across all products sold by a firm or retailer, while the right panels weigh each product by its sales to reflect its importance in the seller’s portfolio. In both cases, the slope is upward—larger firms and retailers are more likely to raise prices as inequality rises, while smaller ones are more likely to lower them.

Figure 1. Price change from a one-standard-deviation increase in inequality, 2004

These results tie directly into two major trends that have reshaped advanced economies in recent decades: the rise of “superstar” firms and widening income inequality. Since the 1980s, company profits have grown while workers have been getting a smaller share of the national income, a shift many studies trace to the growing dominance of large firms. At the same time, income inequality has increased sharply, changing who buys what and how much. Our findings suggest that these two developments are not independent. Rising inequality can tilt the competitive landscape in favor of large firms by allowing them to raise prices on the products that dominate consumer spending. In this way, inequality and market concentration may reinforce each other—one amplifying the other over time.

To make sense of this pattern, we build a simple model that asks how a firm would set prices when selling to consumers with unequal incomes. Imagine, for example, a company deciding how to price a 12-pack of soda. The product is identical everywhere, but the mix of shoppers differs: in some counties most households earn roughly similar incomes, while in others the income distribution is much more spread out. Would the firm charge the same price in both places? The answer depends on how inequality changes the sensitivity of overall demand to price. If a wider income spread (more inequality) makes aggregate demand less sensitive to changes in price, firms can raise prices without losing as many buyers. If it makes demand more sensitive, prices will fall.

We derive general conditions for each case. How much inequality affects prices depends on two features: (i) how strongly demand increases with income and (ii) how quickly price sensitivity itself changes with income. When demand grows slowly relative to income but wealthy buyers aren’t as sensitive to price changes, demand is reduced but won’t significantly change based on price changes. This allows firms that already operate at large scale to charge higher prices while smaller firms are pushed toward lower ones.

This mechanism is not about classic price discrimination or rich and poor consumers shopping in entirely different places. In the data, most retailers serve a broad mix of income groups, and most barcodes are bought by households across all income quartiles. That leaves little room for stores to segment markets cleanly by income. Even after controlling for retailer and local differences, the pattern we document remains unchanged. It’s also not just a matter of richer households spending more on large-market-share products. When we explicitly control for shifts in who buys what, the inequality effects stay virtually the same. The key is not who shops where, but how inequality reshapes demand sensitivity in markets where everyone faces the same posted prices. In other words, higher income inequality allows large firms to charge more for goods with higher demand, exacerbating existing inequality.

Is this just a U.S. retail story? We tested the idea in a very different setting: Chinese firms exporting to many destinations between 2007 and 2015. Instead of barcodes, we observe firms’ unit export prices using universal classification codes that identify goods in detail across destination countries with different income dispersion. We compute unit export prices for each product by dividing the shipment value by shipment quantity, and then compare how the same firm prices the same narrowly defined product across destination countries that differ in income dispersion. The qualitative result reappears: destinations with wider income gaps see higher unit export prices for widely sold, higher-value products and lower unit export prices for thinly sold, lower-value products. Although Chinese data is less detailed and unit export prices can reflect quality choices, the same price-tilting logic shows up, suggesting the mechanism travels.

Policy and governance implications

Our results point to a broader lesson: rising income inequality doesn’t just change who earns and spends more—it changes how firms set prices and how market power evolves. When inequality widens, large sellers gain room to raise prices, pushing up average markups. This isn’t about rich and low-income people shopping in different stores; it’s about a mix of people with unequal incomes making aggregate demand less price-sensitive exactly where big-seller products sit. Large firms can lift prices with less customer loss, while smaller rivals feel pressure to hold or cut prices. Over time, the result is a quiet reinforcement of concentration and pricing strategies that favors incumbents.

Because inequality affects how large firms price high-value products, policies that reduce inequality can influence pricing behavior and lower average markups across the economy. Conversely, policies that widen inequality may push markups up. Essentially, measures that shape the income distribution—such as progressive taxation, targeted transfers, or stronger collective bargaining—affect not only incomes but also prices. These policies must also take into account how standard inflation indexes fail to account for differences in the prices of goods between countries with more and less income inequality. Competition and monetary policy can no longer ignore this factor.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.