In new research, Michele Fioretti, Victor Saint-Jean, and Simon Smith show that shareholders with potential reputational gains will push for corporate actions in the face of shocks like Covid-19 or the Russian invasion of Ukraine that reduce returns to other shareholders who have no reputational gains at stake.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck and, later, when Russia invaded Ukraine, many companies found themselves in the spotlight. Some pledged millions in donations to alleviate families’ financial difficulties caused by the pandemic while others abruptly pulled out of Russia. These decisions were often praised as moral leadership, and companies were lauded for “doing the right thing.” But in new research, we suggest they were also shaped by the reputational incentives of a few prominent shareholders—and that other investors quietly paid the price.

Our central finding is that visible individual shareholders often push firms into costly, highly visible prosocial actions that enhance their personal reputations but erode the returns of less visible investors. This challenges the common assumption that shareholders broadly share the same goal of maximizing firm value. Instead, some shareholders pursue private reputational dividends, leaving others to shoulder the costs.

Reputation as a private dividend

The study identifies reputation as a form of “private dividend” that certain investors can extract from corporate decisions. Prominent individual shareholders—founders, heirs, or public figures—are often closely associated with the companies they own. When a firm donates generously or exits a controversial market, the media often highlights these individuals by name, boosting their public image. For example, in 2016, John D. Rockefeller’s descendents pushed for a divestment from Exxon Mobil—founded by Rockefeller himself—as public concern over climate change rose.

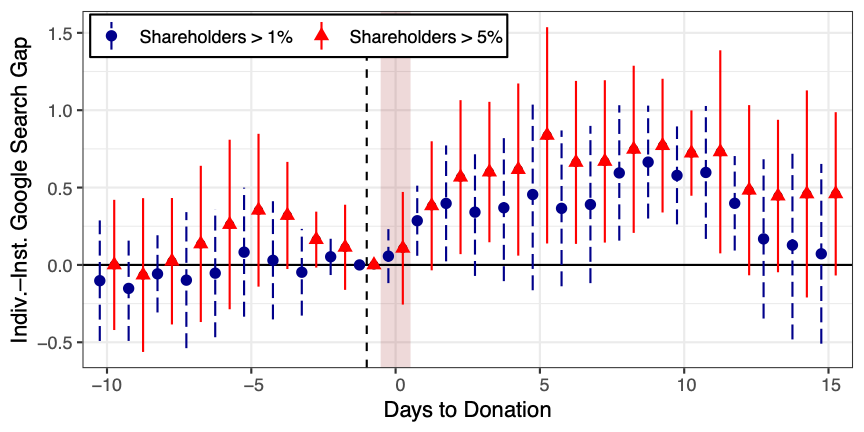

To capture reputational effects, we track Google Search activity. After a firm listed on the S&P donates or exits a market, searches for individual shareholders surge—often doubling—over the next two weeks, while searches for institutional investors remain flat. Figure 1 illustrates this divergence: the gap in search intensity is especially pronounced for large individual shareholders (red triangles), who are more strongly associated with their firms. To give a sense of scale, a 0.4 increase in the gap on the Y-axis translates into about a 75% jump in search activity. The reputational payoff is therefore concentrated among visible individuals, while financial institutions remain largely anonymous.

Figure 1 – Individual shareholders receive more Google searches after a firm donates

Note: the y-axis reports the difference in Google Trend Scores between Individual and Institutional investors in the same firm around a donation event. The figure displays two analyses: blue dots compute this difference for all shareholders with at least 1% shares, while red triangles compute it for shareholders with at least 5%. The latter are generally more easily recognizable to the public than smaller shareholders. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

A distinctive feature of the study is its use of timing. Annual general meetings (AGMs) are set months in advance, meaning some meetings coincided with moments of intense media attention, such as the outbreak of COVID-19 or the invasion of Ukraine. Firms with AGMs during these periods suddenly found themselves under a spotlight. Figure 2 focuses specifically on the pandemic. Because rules from the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) tie AGM dates to those of the previous year, companies with meetings scheduled before April 15, 2020 had set their dates well before the first COVID-19 case. In particular, since the first U.S. COVID-19 case was reported on January 15, 2020, all firms with AGMs scheduled before mid-April 2020 had already set their dates before the pandemic began. Notably, the SEC allowed firms to change their AGM date from mid-April. This makes AGM timing before April 15 predetermined and thus exogenous to managerial preferences regarding donations, the pandemic, or other firm characteristics. It also allows us to identify which shareholder types supported or opposed donations by comparing firms that did and did not hold AGMs during these months, focusing especially on groups such as large individual shareholders.

Figure 2 – COVID-19 donations by AGM timing and shareholder composition

Under media spotlights, firms with prominent individual blockholders were far more likely to announce COVID-related donations before April 15 (blue dots). By contrast, firms dominated by large financial institutions were less inclined to donate (red triangles). Many of those institutions chose instead to give directly through their own corporate channels, ensuring reputational benefits without imposing costs on portfolio companies. To quantify the effects, firms with large individual shareholders are about 20% more likely to donate for COVID-19 (or exit from Russia), while firms with large financial blockholders are about 40% less likely to do so.

Notably, firms with AGMs after April 15—those to the right of the dotted line—show no difference in donation behavior. This pattern underscores that what matters to explain the difference in donation rates is not firm fundamentals but the exogenous surge in visibility created by AGM timing.

The cost of doing (visible) good

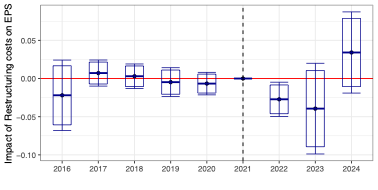

These reputationally driven choices had tangible economic consequences. Firms that donated heavily or exited Russia abruptly saw investment, productivity, and profitability fall by 1–3 percent, with adverse effects persisting for up to two years. Figure 3 illustrates this dynamic: the left panel shows that earnings per share declined, while the right panel highlights rising restructuring costs. In practice, these firms reduced investment, posted weaker earnings, and incurred significant charges to reorganize operations—all outcomes that shareholders without reputational gains were left to absorb.

Figure 3 – Changes in Earnings Per Share (EPS) during COVID-19 (top panel) and restructuring costs on EPS at the onset of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (bottom panel)

In one striking calculation, we show that increasing a prominent shareholder’s visibility by just 1 percent cost fellow investors about $0.025 per share—roughly $163,000 for the median prominent shareholder. To put it differently, ordinary shareholders were effectively subsidizing a reputational campaign at a price comparable to elite public relations services. The scale of the costs was not catastrophic, but it was persistent and nontrivial.

What makes these results notable is not only the magnitude of the costs but their distribution. All shareholders bore the financial consequences, but only a few captured the reputational upside. The pursuit of shareholder “values” thus produced measurable redistributive effects within the shareholder base itself.

An invisible governance friction

This introduces a dimension of corporate governance that is easy to miss. Conventional debates assume that shareholders, despite their differences, share a common interest in maximizing firm value. Yet reputational incentives can pull them apart. Prominent individual shareholders may encourage firms to take costly, visible actions that enhance their personal standing, while less visible investors—unable to capture similar benefits—are left to absorb the losses.

These conflicts are hard to observe precisely because they rarely surface in formal governance channels. In the case of COVID-19 donations, for example, there were no shareholder proposals explicitly demanding corporate giving in 2020. Instead, influence operated through quieter forms of pressure—private conversations, boardroom dynamics, and managerial anticipation of what high-profile shareholders might expect when media attention was high.

As a result, these conflicts amount to an almost invisible source of friction in corporate governance. They are not about managers diverting resources for personal gain—the classic agency problem—but about heterogeneous shareholder preferences colliding beneath the surface. Existing oversight mechanisms, designed to protect minority investors from managerial opportunism, are not well-equipped to address these subtler struggles among shareholders themselves.

Broader consequences

These findings complicate how we think about capitalism’s ability to deliver social goods. On one hand, prominent shareholders’ push for donations and rapid exits can yield positive externalities: hospitals receive supplies or authoritarian regimes lose foreign investment. On the other hand, the mechanism is distortionary—actions are taken not because they maximize shareholder or social welfare, but because they maximize visibility for a few.

This raises uncomfortable questions: Should reputational incentives remain a primary channel for corporate social responsibility, despite the uneven costs? Or should governance be redesigned to make such trade-offs transparent, so that all investors can weigh in?

For policymakers, the research highlights the limits of disclosure and voting systems: if most conflicts never reach the AGM agenda, formal governance offers only a partial picture of decision-making. For boards, the lesson is that influence flows not just from ownership stakes but from visibility. A shareholder with modest holdings (e.g. above 2%) but high public recognition can, at the right moment, exert disproportionate sway.

The broader implication is that the distribution of reputational gains and financial costs will shape the provision of social goods. The pandemic and the war in Ukraine will not be the last moments when firms face demands to act under the spotlight. Climate change, geopolitical tensions, and social justice movements will bring new tests.

Whether such actions turn out to be beneficial or distortionary likely depends on how governance structures evolve. Greater transparency around shareholder–manager interactions could give passive investors a clearer view of when they are being asked to underwrite reputational rents. Mechanisms that encourage broader consensus among large shareholders before costly actions are taken may also help reduce the risk of unilateral influence.

This study suggests that corporate social responsibility is shaped not only by managerial choices but also by the reputational incentives of shareholders. Bringing those incentives into view—and recognizing their consequences—seems crucial for any serious debate about the future of capitalism.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket’s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket’s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.