In new research, Adam Callister, Andrew Granato, and Belisa Pang argue that differing incentives faced by plaintiffs and defendants in “battles of the experts” litigation (like securities suits) leads to structurally higher spending by defendants on expert witnesses. These incentives also apply to any class action suit and many individual suits. They argue that courts should take this dynamic into account and correspondingly be more aggressive in using authority to employ court-appointed experts.

How harmful is asbestos exposure for your lungs? If your relative dies during surgery, does your surgeon’s medical conduct fall within the accepted standard of care? Can a company’s allegedly fraudulent statement cause its investors to lose money?

In recent decades, the legal system has decided questions like these with a “battle of the experts,” where both parties hire dueling expert witnesses to make their case about matters of scientific and social scientific dispute. Our research shows that under standard American class action civil procedure law—and individual litigation that frequently features analogous dynamics—defendants will outspend plaintiffs in an expert witness arms race, creating a structural advantage for defendants.

In our research, we demonstrate empirically that defendant corporations outspend plaintiff shareholders on prestigious expert witnesses in securities class actions. We show why this dynamic extends to a far broader swath of lawsuits across different substantive areas of law and how it ultimately creates an imbalance in the justice system.

The “battle of the experts” in securities litigation

Securities class action lawsuits are, at least in theory, intended to protect investors. The Securities Acts, which passed after the stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression, give shareholders a tool to address corporate fraud. If a securities issuer, like a corporation, makes a statement that is a material misstatement about its business or omits material information that the corporation is required to disclose to investors, shareholders can sue for the money they lost as a result. Such shareholders have to establish “price impact” (that the stock price of the firm declined as a result of the revelation of the misstatement or omission relative to what the stock price would have been otherwise). Dueling economists have long fought to establish price impact through “event studies,” which track how much a stock’s price moved following information revelation while controlling for wider market movements.

High litigation costs would theoretically mean that it isn’t worth it for any small, individual shareholder in a large, publicly traded company to sue. However, in a situation where the harms of an act are diffuse enough that relying on an individual victim to sue would mean functional immunity for the harm-doer, the legal system provides the class action lawsuit solution. Similarly situated plaintiffs, like shareholders who bought into a company in the aftermath of a fraudulent statement but are left dealing with the consequences after the fraud is revealed, can aggregate their claims into a single lawsuit. In practice, class action lawsuits are essentially managed by the lead plaintiff law firm, which has responsibility for litigating the case in court.

In a class action, the plaintiff and defense sides face fundamentally different incentives. Plaintiff-side firms in such cases are paid on contingency, meaning that they receive nothing if the case gets thrown out, but they take a percentage from any settlement or trial award. Previous work has established that securities class action settlements pay out attorney fees of roughly 25% of the settlement’s value for all but the largest cases. But these firms must, in addition to paying their attorneys, also pay for all litigation expenses upfront, including expert witnesses. These litigation expenses, of which expert witnesses are normally the largest part, generally cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, but can climb into the millions. Ultimately, while those expenses are billable to a settlement, reimbursement requires that the firm achieve a settlement, which is hardly a sure thing.

Defendant corporations, meanwhile, pay their lawyers by the hour and, in theory, are responsible for the full value of any settlement or judgment. In practice, they can purchase directors and officers (D&O) insurance that pays those costs directly, but D&O insurers respond to payouts by hiking the firm’s premiums. In our paper, we use a mathematical model to demonstrate that these asymmetric incentives result in lower plaintiff expert spending when the litigation involves outcome uncertainty, a sufficiently low percentage of settlements paid to plaintiffs’ counsel, and a risk for high potential damages.

How out-gunned are plaintiffs?

To test litigant expert spending in securities class actions, we manually search the dockets of every such lawsuit filed from 2008 to 2018 that proceeds beyond the motion to dismiss stage. We find 1,289 expert appearances, 756 filed expert reports, and 947 observations where we can directly observe hourly expert compensation or impute expected compensation from nearby data on the same individual. Our analysis produces three stylized facts that we collectively call “expert asymmetry.”

Stylized Fact #1: Securities litigation experts are dominated by repeat players who are almost completely polarized as either “plaintiff-side” or “defense-side” experts. Out of 140 experts for whom we observe at least two appearances, 89% appeared either exclusively for plaintiffs or exclusively for defendants. A similar polarization is evident among the most frequently repeating experts, including one expert who we identified as appearing on behalf of plaintiffs 75 times—over 20% of all cases in which we were able to identify a plaintiff-side expert. This polarization extends to expert consulting firms, like Cornerstone, which appears on behalf of defendants 181 times but on behalf of plaintiffs zero times.

Stylized Fact #2: Defendants hire experts with more “prestigious” educational and academic affiliations. For example, defense-side economic experts are more likely to hold Ph.D.s, more likely to have been granted those Ph.D.s from universities that U.S. News considers to be in the “top 15,” and more likely (if they are professors) to be placed at “top 15” departments.

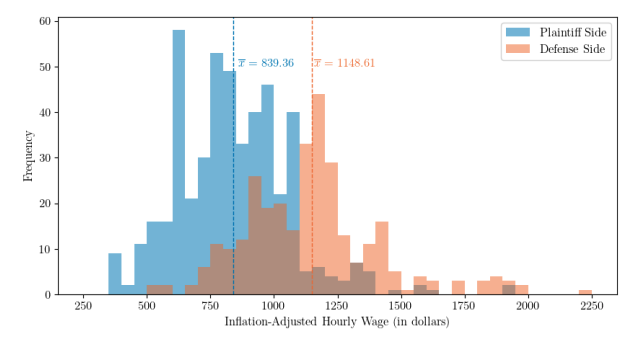

Stylized Fact #3: On average, defense-side economic experts are paid at least 37% more per hour than plaintiff-side experts ($1,149 per hour vs. $839 per hour). (We say “at least” because while we can see hourly wages in expert reports, some defense-side experts also report that they receive a percentage of total billings their consulting firm receives.) We show the overall distribution of economic expert hourly compensation below, adjusting wages for inflation to 2024 dollars:

We run regressions and conduct other analyses to establish that this difference in means remains roughly the same regardless of the test we run. We also test various empirical predictions that our mathematical model makes, such as predicting that the level difference in expert spending between sides will increase as the stakes of the damages claim increases, and find that they are borne out.

We emphasize that the logic we articulate for why defendants outspend plaintiffs in securities class actions is not exclusive to such cases. While the degree of outspending may differ in other contexts, the logic applies to any context where one side is paid on contingency but the other is not. Plaintiffs’ counsel in all class actions is paid on contingency, as is counsel in many individual cases. Indigent plaintiffs, for example, are forced into contingency fee structures whenever they want to try to vindicate their rights in court because they cannot pay lawyers any other way. Some form of “expert asymmetry” likely exists across all domains of law that rely on “battles of the experts” for this reason.

Is “expert asymmetry” a problem? We argue that it is a problem whenever the law is functioning properly and decides cases on the merits. If plaintiffs lose meritorious cases that they would have won because they were outgunned on the field of experts-for-hire, then the legal system is rewarding defendants for procedural rather than substantive reasons. To remedy this defense-side advantage, we argue that judges should be more willing to invoke Federal Rule of Evidence 706 (and state law analogues) to appoint expert witnesses themselves, especially in high-damages cases where “expert asymmetry” is most likely to appear.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.

Subscribe here for ProMarket‘s weekly newsletter, Special Interest, to stay up to date on ProMarket‘s coverage of the political economy and other content from the Stigler Center.