Why is nonprofit ownership gaining traction in the U.S., with companies like OpenAI and Patagonia mirroring long-standing models in Europe, such as Novo Nordisk and IKEA? In new research, Ofer Eldar and Mark Ørberg unpack the economic rationales behind nonprofit business ownership, challenge the idea that it’s all about purpose, and highlight the overlooked risks of nonprofit control.

Nonprofit control of business enterprises is a long-standing feature of the European corporate landscape. Household names like Novo Nordisk, Carlsberg, and Rolex are controlled by nonprofit foundations—a structure that ensures continuity and long-term orientation, though not always for the reasons many might think. More recently, this model has gained attention in the United States, especially with high-profile examples like Patagonia and OpenAI. These developments have prompted a broader conversation: Is nonprofit control of businesses a viable alternative to traditional shareholder capitalism?

Many advocates suggest it is. Colin Mayer and others have praised nonprofit-controlled firms as vehicles for embedding corporate purpose and sustainability into the core of business strategy. Cathy Hwang and Dorothy characterize such structures as “purposeful enterprises” that elevate organizational purpose, insulate firms from shareholder pressure, and potentially reduce agency costs while promoting long-term stability and stakeholder alignment. Yet, as we show in our forthcoming article in the Yale Journal on Regulation, “The Anatomy of Nonprofit Control of Business Enterprise,” these narratives often oversimplify or mischaracterize what nonprofit control actually entails in practice.

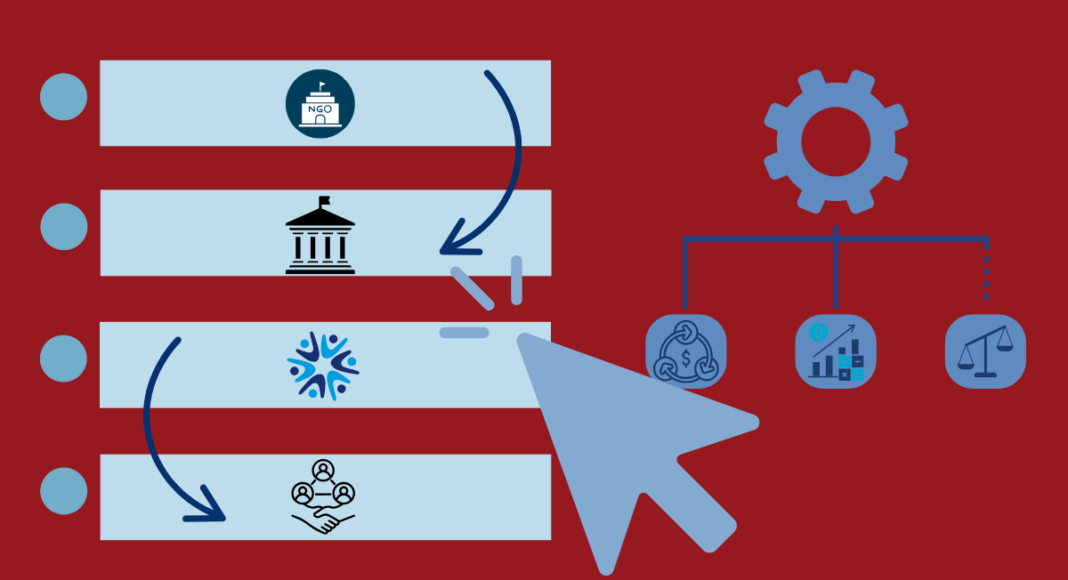

The key insight of our work is that there isn’t a single model of nonprofit control. Instead, we identify two dominant models. The first is the income-generating model, where a nonprofit controls a business not because it has a social mission, but because it reliably generates cash. This model is especially common in Europe, where firms like Novo Nordisk and Carlsberg provide consistent income to their nonprofit controllers. These businesses operate largely like ordinary commercial firms—selling pharmaceuticals, beer, or furniture—but their profits are directed toward the nonprofit’s charitable mission. Rather than relying on donations, the nonprofit substitutes earned income as a major funding source. Much like family-owned firms that fund long-term consumption, these nonprofits prioritize stable cash flows and retain control over profit distribution decisions.

The second model is the socially oriented for-profit. Here, the nonprofit’s goal is not to extract cash but to embed and enforce a social mission within the for-profit’s operations. This structure is essential when the business mission diverges from profit maximization and would likely be abandoned under conventional ownership. These firms include social enterprises that work with disadvantaged groups—like work-integration programs or fair-trade organizations—as well as businesses that seek to provide public goods, such as environmentally friendly production processes, sustainable technologies, or AI safety. In these cases, nonprofit control is supposed to serve as a commitment device: a way to ensure that social goals are not diluted by profit pressures.

While these models are conceptually distinct, they are not mutually exclusive. Patagonia is a case in point: it distributes profits to a nonprofit while also being governed by a purpose trust that seeks to uphold environmental sustainability through the business itself. In hybrid cases like this, tensions can emerge between the need to fund charitable causes by the nonprofit and the need to reinvest profits toward the social mission of the for-profit business.

Each model comes with risks. For income-generating nonprofits, the main concern is mission drift at the nonprofit level. In particular, if the nonprofit is overly focused on managing the business, it may fail to secure distributions needed to carry out current projects that further its charitable purpose—especially when outside investors may prefer to reinvest profits to grow the business. This risk, however, is relatively small because both the nonprofit and for-profit investors (if any) are focused on long-term cash generation.

For socially oriented for-profits, the greater risk is that profit pressures will overwhelm the social mission, especially when outside investors are involved. The case of OpenAI is instructive. Though formally controlled by a nonprofit, OpenAI’s dependence on Microsoft—both as an investor and commercial partner—has raised questions about whether its public-benefit mission remains credible. When a minority investor holds significant leverage, even formal nonprofit control can be hollowed out.

Legal regimes across jurisdictions address these challenges in widely diverging ways. European and British systems, for instance, support nonprofit ownership through enterprise foundation laws—statutes that allow foundations to own and control business enterprises —and charity structures, with requirements for income distributions and regulatory oversight. The United Kingdom further accommodates socially oriented for-profits through a social investment regime that allows charitable organizations to invest in firms with dual goals. In both cases, supervisory authorities help mitigate the risk of mission drift by monitoring compliance with charitable purposes.

The U.S., however, takes a more fragmented approach. Private foundations are heavily restricted: under the “Newman’s Own” exception, they may only own a for-profit if it distributes all its income and has no outside investors. Program-related investments (PRIs), designed for socially oriented for-profits, also face burdensome compliance rules. In contrast, public charities or perpetual purpose trusts (essentially nonprofits, as they have no owners) have wide latitude to control businesses—without many of the safeguards that apply to foundations. This regulatory gap explains how OpenAI, a public charity, could end up in a situation where profit-oriented investors appeared to direct its strategy.

In light of our economic and legal analysis, we outline an optimal legal regime for nonprofit control of business enterprises. First, legal systems should set different rules for income-generating and socially oriented nonprofit control, as well as for businesses that combine the two models. These are distinct economic models with different vulnerabilities. Second, rules should ensure that income-generating for-profits do not accumulate assets and make reasonable distributions to their nonprofit controllers, as required in European jurisdictions with a robust presence of enterprise foundations. Third, socially oriented for-profits should face more rigorous oversight, especially when outside investors are involved. Certification regimes may mitigate the risk of mission drift, particularly where the purpose is to increase access to capital or provide employment for disadvantaged groups. Otherwise, the standard tools of strong government enforcement and disclosure requirements—albeit imperfect—may be necessary.

Relatedly, we argue that the current regulatory focus on donor or founder independence—particularly in the U.S., which imposes heightened restrictions on foundations (essentially, nonprofits that receive the bulk of their funding from a single founder)—is misplaced. The more serious concern is influence from financial investors whose incentives diverge from the nonprofit’s mission. Independence from such investors should be the real focus of legal design, and unless donor-founders have a financial stake in the for-profit, there is little justification for limiting their influence.

In summary, nonprofit control of business enterprises isn’t always about purpose—but it isn’t just about profit either. It’s a flexible governance tool that can serve different objectives depending on context. Our aim is to provide a framework for understanding this diversity and for designing legal regimes that reinforce the benefits while curbing the risks. If we’re serious about using nonprofit ownership as a mechanism for enhancing social welfare, we need to take seriously the true economics of nonprofit control.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.