New research from SP Kothari, Hamid Mehran and Zirui Song argues that share buybacks – rather than traditional dividends – may actually be safer for financial stability since they offer banks more flexibility and don’t signal distress when reduced. The authors show that while dividends create pressure for consistent payments and industry-wide ripple effects when cut, buybacks allow banks to adjust their capital distribution to the present circumstances.

Bank managers’ decisions to distribute payouts to equity investors are among the corporate decisions with the most significant public policy implications. Usually, a bank rewards investors with either dividends or stock buybacks when their share prices and earnings are high. The market typically greets these payouts with stock price increases. As a result of the subsequently higher equity valuation and more equity capital, banks can engage in more lending to various sectors of the economy and contribute to economic growth.

However, a high bank payout in the absence of a sufficient capital buffer could impose a big cost on a bank’s stakeholders, including the public, if the bank experiences a negative shock event. The impact and the nature of shocks are uncertain, so anticipating the size of a buffer necessary to survive the shock is difficult. Bank management must navigate a fine line between creating value through payouts and serving the public interest through financial prudence. This is especially important because banks rely on government safety nets when facing difficulty, and particularly during crisis.

The intuitive response to this balance, and what has become the public expectation, is to limit bank payouts in order to preserve confidently adequate capital buffers. Many banks and their management are criticized in the press and by lawmakers for their due diligence failures to forgo payout (and build up capital) since the global financial crisis. (See Admati, et al. for a comprehensive discussion on cash dividends and financial stability). Especially in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the passage of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, regulators have begun paying close attention to bank payouts. They seek to ensure that payouts align with the banks’ capital plan in their annual stress test (see Floyd, et al. and Fahlenbrach et al. for further discussion). The focus on bank payouts received further attention by regulators following the 2020 global pandemic, both in the United States and in Europe. Our aim in this post is to shed light on the composition of bank payouts, namely dividends versus repurchases, from the perspective of a banking firm seeking to create value while taking public interest into account.

Walking the tightrope

Creating economic value through payouts to banks’ shareholders requires flexibility regarding how much and when to pay equity holders in a way that minimizes potential regulatory scrutiny. Lowering or cutting dividends usually initiates an equity price decline and management turnover among nonfinancial firms, although little is known about management turnover among the U.S. banks following dividend cuts partly because of the infrequent manager churn outside of a period of crisis. When a bank omits or cuts dividends, it experiences a stock-price decline of about 8% to 11% at the time of announcement. The banking industry also suffers from ripple effects when a bank cuts its dividend. The market might infer dimmer prospects for the entire industry and anticipate that other banks will cut their dividends as well.

A potential explanation as to why banks are reluctant to cut their dividends in addition to the loss of value is that doing so could induce increased regulatory oversight, and thus a decline in discretion. Regulators may also be reluctant to force a weak bank to cut its dividend out of concern that investors may flee the whole industry, thus counterproductively inducing panic. For example, regulators opted out of forcing Citibank to cut its dividends in the 90s. They worried that other banks might suffer if the market learns about the bank’s financial losses as well as its risky condition.Further, enforcement action to cut dividends requires timely downgrades, and supervisors are often late in downgrading weak banks. Instead, regulators are more likely to encourage the bank’s acquisition by a stronger bank. This was not a possibility for Citibank due to its size. Thus, by not forcing a bank to cut its dividends, regulators in effect conceal the bank’s private information from the public and raise the likelihood of using public resources to save the bank.

The financial crisis and the passage of the Dodd–Frank Act might have addressed the supervisors’ dilemma on bank payouts for the largest U.S. banks. Instead of asking banks directly to alter their payout (as well as capital structure and other corporate policies) that impact their health and stability, banks are required annually to submit their capital plans and distributions for various hypothetical economic scenarios to regulators in what’s known as a “stress test.”

This practice is not likely to stigmatize banks as no private bank information is released. Also, in the process, banks would be given an opportunity to submit their revised plans within 48 hours before stress test announcements should there be concerns by regulators about their submitted capital plans. Further, in a steady state, the release of stress test results should not convey any news to the market as all banks, except the weakest, are likely to alter their corporate policies to pass the test. In the absence of a stress test, both the banking sector and regulators should worry about dividend increases, even by a single bank, particularly if it might not be sustainable. Acharya, et al. (2016) focus on dividend externality by banks. They show how payout changes by one bank impact other banks and, thus, financial stability.

Share repurchases, on the other hand, are an effective remedy for the bank dilemma on dividend payouts. Banks could announce many repurchases over several years, with the timing of payouts being discretionary and when they are healthy. By lowering or increasing their repurchases in one year, a bank would not impact the entire industry’s financial stability, as there is no expectation that the payouts are permanent. For example, Truist Financial Corporation ($520 billion in assets) announced on June 28, 2024, that its “board of directors has authorized a $5 billion share repurchase program through 2026 as part of the Company’s overall capital distribution strategy.” It added that “[t]he share-repurchase program does not obligate Truist to acquire a specific dollar amount or number of shares and may be extended, modified, or discontinued at any time.” This suggests that Truist, like most banks, will not commit to a guaranteed payout in repurchases, even after they have been announced. Clearly, regulators should support the repurchase approach, as it allows banks to control their operating costs more effectively through repurchases, and their credit spreads and ratings should improve as well with the benefits passed on to bank customers.

Despite the elegance of the share repurchase payout method, dividend payouts will still be necessary, as there must be some distribution to commit the firm to payout to its owners. This ensures efficiency and value creation in an industry that is highly concentrated. In addition, Floyd et al. suggest that by paying dividends, banks aim to convey their future growth. Also, banks might want to pay some dividends as some fund managers only invest in stocks that pay dividends. Further, paying dividends is a way to distribute funds to individual investors who are less likely to participate in buybacks (according to a bank analyst).

From the perspective of the firm, opting for more distributions in repurchases that are discrete choices versus committing to a permanent expectation of annual cash dividends could help in passing their stress tests as they could control their operating costs more effectively. The market, however, is likely to prefer a cash dividend scheme due to their greater permanence. Thus, bank management needs to overcome the tension in payout structure. A greater reliance on repurchase plans might induce riskier decisions as the bank makes no payout commitment. Further, since the cost of risk taking is partially internalized by forgoing buybacks, the bank credit rating is less likely to be adversely impacted.

Do stock buybacks induce financial instability?

To test for stability, we examine total payouts and consider the mix of the payouts for three cohorts of banks: Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs), large banks, and regional banks. We define G-SIBs as banks that have more than $700 billion in total assets in the previous quarter, large banks as those with between $100 and $700 billion in total assets in the previous quarter, and regional banks as those with between $10 and $100 billion in total assets in the previous quarter. All asset values are inflation-adjusted by 2023-dollars. We present evidence on bank payouts, cash dividends, and repurchases over the period 2004Q1 to 2024Q2. Our data sources are Compustat quarterly financials and Thomson Reuters Institutional Managers’ (13f) Holdings of publicly listed U.S. commercial banks.

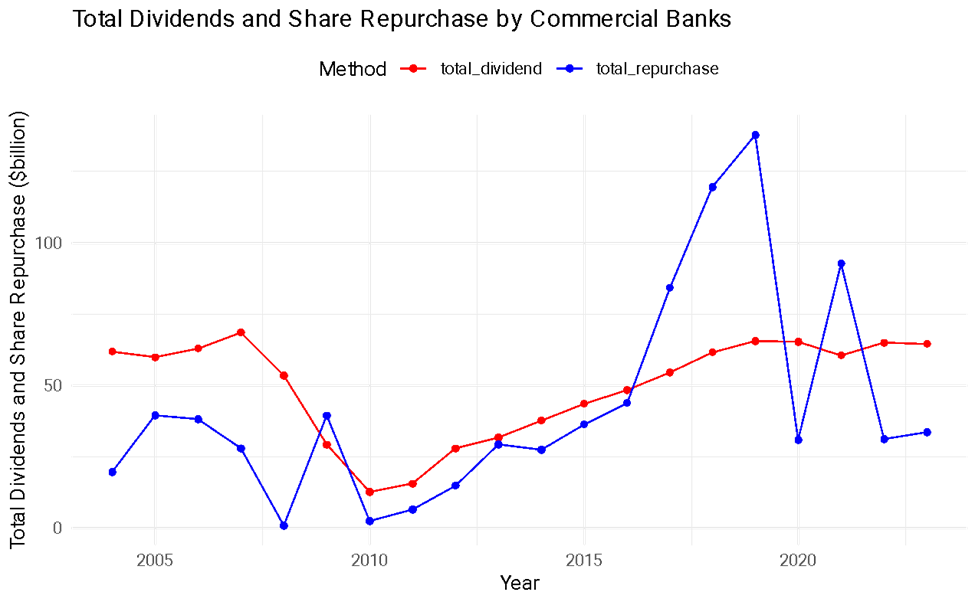

While dividend payouts have been the main method of bank payout throughout the sample period, share repurchase activity has increased in recent years. From 2017 to 2019, banks repurchased around $340 billion in shares, a large amount relative to dividend payouts of around $180 billion during the same period. Furthermore, while dividend payouts have stayed relatively stable over the years, share repurchases have fluctuated dramatically over the same period. These results suggest that banks have been reluctant to change their dividend policy and instead tend to conduct share repurchases to supplement aggregate payouts.

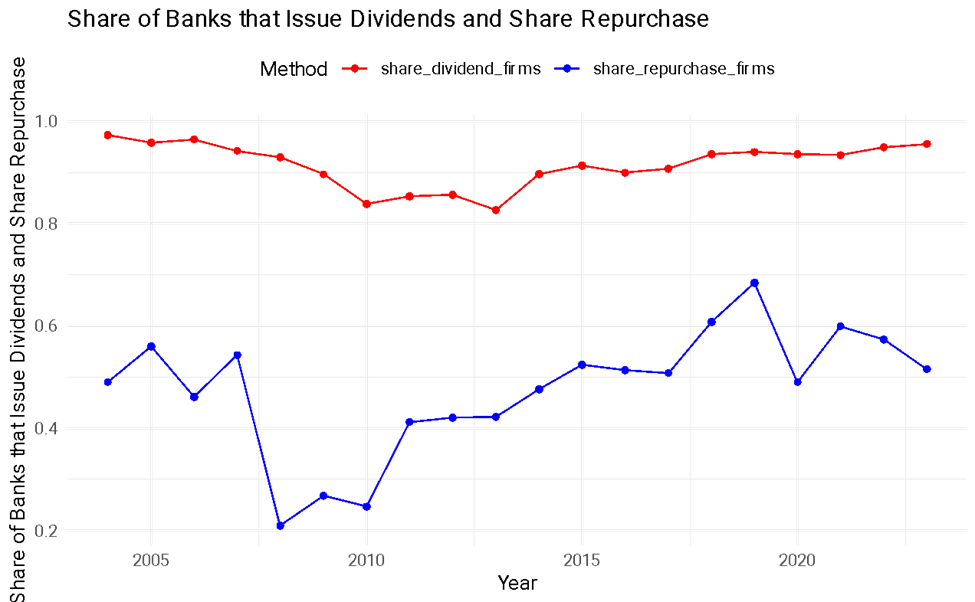

More than 80% of banks issued dividends in any given year from 2004 to 2024, while the share of banks engaging in share repurchases has fluctuated from only 20% in 2008 to more than 60% in 2019. Again, these descriptive results indicate that banks have been much more flexible in altering their share repurchase behavior than changing their dividend payout policy.

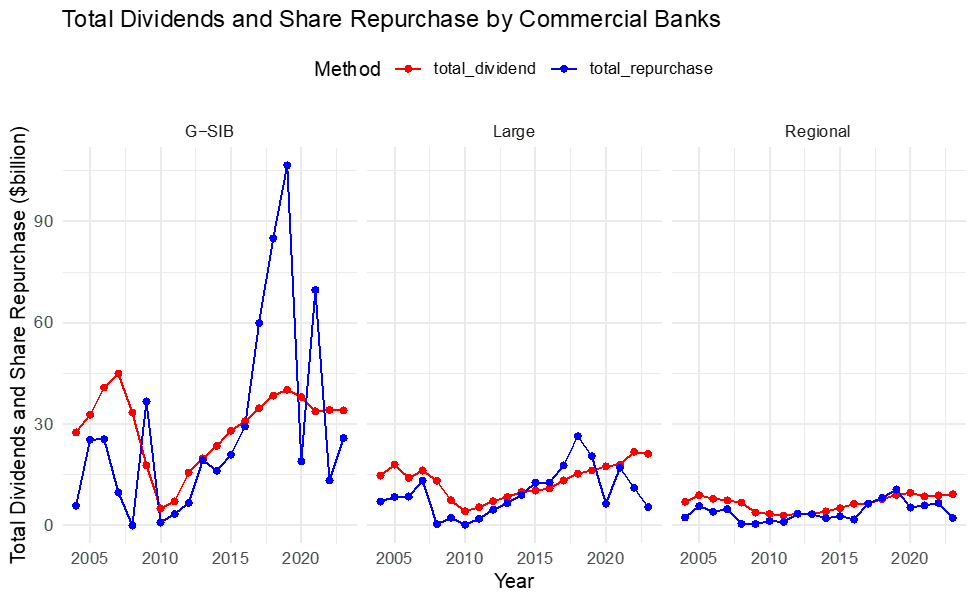

Having documented the aggregate trends of bank payout, we examined the total dividend and share repurchase amount in each year separately for each bank cohort. Results indicate that G-SIBs and large banks contributed most of the share repurchase (bank payout) activities in the last three decades. Most of the fluctuations in share repurchase activity came from share repurchases by G-SIBs.

Dividend payout, on the other hand, was much less volatile especially for the G-SIBs. Between 2017-2019, dividend payout for G-SIBs stayed relatively flat while share repurchase amount jumped to more than $100 billion in 2019 from only around $30 billion in 2016. On the other hand, the increase in the share repurchase amount for large and regional banks was much smaller in the same period.

In the last part of the analysis, we examine using various regression models whether share repurchase activity creates fragility in the banking sector. To investigate this, we analyze how share repurchase activity is associated with tier 1 capital ratio and earnings. We find that tier 1 capital ratio is positively associated with both the propensity to issue share repurchases and the amount of the share repurchase. Moreover, banks are more likely to repurchase shares when they have higher earnings. Share repurchase activities typically occur when banks demonstrate strong earnings and are well-capitalized. Consequently, there is not enough evidence suggesting that share repurchases contribute to financial fragility. Interestingly, while stock buybacks have been large in recent years, the tier 1 capital ratio increased slightly for G-SIBs, partly due to regulatory reform targeting the largest banks. These descriptive results suggest that share repurchase activity did not contribute to the deterioration of banks’ equity buffer.

To summarize, we examine bank total payouts to its owners and composition of payouts in cash dividends and share repurchases. We find that total payouts have increased over time, with share buybacks growing faster and being more volatile, supporting the argument that the scheme can help the bank to manage its operating costs more effectively while minimizing regulatory concerns. While it is tempting to conclude that regulatory oversight and stress test might have been the driver of growth in buybacks in the banking industry, other factors could have influenced the trend. For example, share repurchases have grown in nearly every industry and their growth started earlier than in banking.

Author Disclosure: the authors report no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.